Three Questions: On Translation with Eliot Weinberger

by Roman Antopolsky / June 17, 2011 / 1 Comment

“If there were no more works in translation, we’d all be a lot dumber.”

In Three Questions, Sampsonia Way’s new series, we ask world-renown translators three questions about their work, reflecting the oft-quoted statistic that in the United States literature-in-translation makes up approximately 3 percent of the literary marketplace.

However, in this interview conducted by Roman Antopolsky, translator Eliot Weinberger explains why that number isn’t entirely accurate. He mentions another 3-–this time preceded by a decimal point.

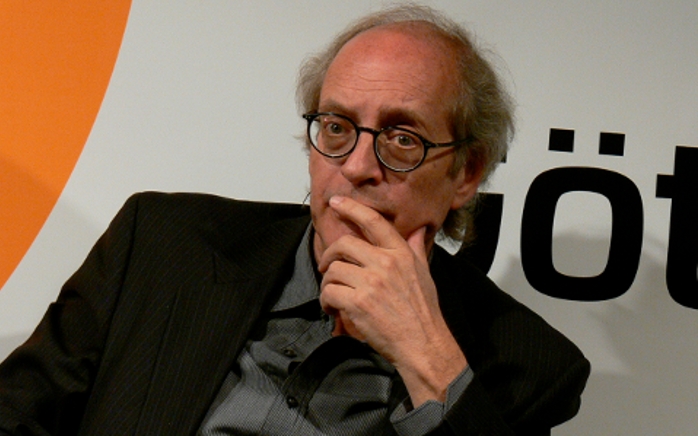

Eliot Weinberger, Photo: Litlog

Eliot Weinberger, a writer, essayist, editor, and translator first gained recognition for his English translations of the Nobel Prize-winning writer and poet Octavio Paz. His translations of Paz’s work include the Collected Poems 1957-1987, In Light of India, and Sunstone. Among Weinberger’s other translations are Vicente Huidobro’s Altazor, Xavier Villaurrutia’s Nostalgia for Death, Jorge Luis Borges’s Seven Nights, and Bei Dao’s Unlock. His edition of Borges’ Selected Non-Fictions received the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism in 1999. Today, Weinberger is primarily known for his literary writings and political articles, including Karmic Traces, An Elemental Thing, Oranges & Peanuts for Sale, and What I Heard About Iraq.

With translation making up only 3 to 5 percent of what is published annually in the United States, you have undertaken the daunting task of translating relatively unknown Spanish and Chinese poets into English for a market that is not very open to foreign writers. How would you characterize the reception of your translations in such a context?

First, the 3 to 5 percent that one always hears is completely false. There are about 100,000 new books published by real publishers every year in the USA, and another 200,000 published through internet vanity publishers. Excluding scientific books, technical manuals, and textbooks, the number of new literary translations of all kinds—poetry, fiction, classics, criticism– published by legitimate large, medium, university, and nationally-distributed small presses is around 300 to 400 titles a year, at most. So the statistic is nowhere near 3 percent– it’s more like 0.3 percent.

That said, I also don’t agree with the equally-often asserted claim that US readers are not open to foreign writers. If one looks at mass-market books, the No. 1 bestsellers of the last year or so have been the novels of [Swedish author] Stieg Larrson. Spanish thrillers and [French writer] Muriel Barbery are also on the bestseller list. If one looks at what James Laughlin of New Directions used to call “serious literature,” it’s safe to say that, in recent years, the only two writers whom everyone I know has read are Roberto Bolaño and W.G. Sebald. I can’t think of an American writer who has made that kind of impact.

So it’s statistically quite true that the US translates much less than any European country. But a great deal of what the Europeans are translating are American thrillers and science-fiction. Of course they translate many more serious novels, and not all that much poetry, but the huge numbers that are usually cited are misleading.

In my own case, I have translated two writers who are enormously popular among literary readers: Octavio Paz and Jorge Luis Borges. But what interests me are the more obscure writers. For example, in the early ’90s I translated Xavier Villaurrutia, who is famous in Spanish, but completely unknown here. Almost no one read the book. But last year in Delhi I met a young Indian writer, Rana Dasgupta, who has written a wonderful novel, Solo, that takes place entirely in Bulgaria and ex-Soviet Georgia. There’s nothing “Indian” in his book at all. One of the characters is a hapless poet, and one of the poems he writes is one of my translations of Villaurrutia. Dasgupta told me he had accidentally come across the book, and it was one of his favorites; this seems the ideal reader– or at least the ideal story of a translation.

Finally, I don’t think translation is so arduous. They always have these academic conferences, which I don’t attend, on the “Problems of Translation,” but never on the “Pleasures of Translation.”

You have written: “The poem dies when it has no place to go.” What kind of poetry is entering the United States now? How do you see poetry’s movement around the world?

As in the story of Dasgupta and Villaurrutia, poetry always moves through hidden channels, regardless of nations or programs or committees. Translated poems, like poems in their original language, have a way of appearing and changing a person’s life.

In the ’60s, when there were relatively few American poets, it was possible to say that the new translations of Latin American and Eastern European poetry were having an enormous effect on many different types of American poetry. Certainly much of American poetry throughout the 20th century is inconceivable without the lessons learned, strangely enough, from classical Chinese poetry. I can think of various examples where, in the work, it is obvious that a specific American poet has been reading a specific foreign poet. However, today there are far too many poets to make any general statements about American poetry as a whole.

What would happen if all translation ceased?

We’d all be a lot dumber.

Read more about translation:

A conversation on translation between three international authors and Dalkey Archive Press’ publisher John O’Brien.

Two Essays by Katherine Silver:

The Erotic Place of Translation

Literary Translation and Subversion

One Comment on "Three Questions: On Translation with Eliot Weinberger"

Trackbacks for this post