Dis Tortue, Dors-Tu Nue? by Lia Villares

by Sampsonia Way / September 17, 2013 / No comments

Translated by Juan O. Tamayo

Fog in the mornings, hunger for clarity,

coffee and bread with sour plum jam.

Numbness of soul in placid neighborhoods.

Lives ticking on as if.

Adrienne Rich

B gets up and goes to the shower. Doesn’t close doors or draw curtains. The water runs vaporously, terrifyingly. Bends to open the blinds, the gown open.

—Dis-moi, what is the best?

—The best and the worst, like the Bukowski poem?

—For him, it was the whores, the beer. The worst: The work, the police stations, the terminals.

—Let’s see, the best is to bathe together. And your mother’s rice pudding.

—For me, the best is the light. Your skin, the hues, what I can’t manage to see, what I see too much of. Before and after, the nights at the Cinemateque, with Helmut Kautner. The photography course only-for-aficionados. The watery and hot cappuccinos on the little table beneath the fly trap: Electric trap for bugs, shaking us with each capture, zapping sound included. Without changing places, reading the tired, almost-never-happy faces of the regulars. We’re dying with disgust. More. The couples stopped by the window pane, faces of hand-holders looking for a place, some empty table for two. The estrangement always evoked by the discredit or that childish surprise over everything that at some point was drawn on its own face. Youthful exhibitors of daily stupidity, an expanded emptiness. The crazy guy with his Walkman moving his head, or paying attention in the dark hall to the fleeting hand that slides along the peeled walls of the stairways of Wong Kar-Wai. The waitresses vomiting their boredom into cups. A vomit of sorrow. Of lack of desire and insignificance.

- Lia Villares

- Fiction writer, musician, blogger, visual artist.

- Lia hasn´t yet published any books. Her writing is herself, her motley room full of incense and music, her diaries half-finished or half-begun, her incredible blogs all of them called “Hechizamiento Habanémico Hebdomanario.” Her stories have appeared in national magazines and anthologies, but most of her creativity goes into the digital world, where she is one of the most important social activists of Cuban blogosphere.

- Read more…

—And what else?

—The alcohol burner and the saltpeter, one guitar-playing friend used to say. Linen clothes, sans doute. To read Bukowski on the toilet. To write dirty poems.

—Bob Dylan in halves: Midnight and half a bottle of whisky for two.

—Tim Burton poems in the Inbox.

—The best, j’insiste, does not include me?

—Let me see… What’s missing are new books, to hibernate under the blankets, the slippers from Quito…

—Count Basie. Your bedroom at three in the afternoon, if it was possible to isolate it from the telephone-streets-buses.

—Black tea, chocolate with cinnamon. Milord at the accordion, Edith on the speakers.

—Now you’re starting to include me.

After and before on the night buses, fuller than the moon and the bellies. The windows open, stained with collective sweat. To linger, watching a fat woman leaning on a grey, dirty wall. A tiny dress the color of skin, the bare skin coming out of the scanty, tight silk. The girl(s) of thirteen, the downy hair behind the neck, the back, the bony shoulders. Straps fallen from a blouse that holds in the hint of all-too noticeable areolas. (Just looking at her you get goose bumps. When a seat is free you take it, and fast, to be direct: Come, don’t you want to sit on me? And she does not hesitate: She leans back, her lightness taking your breath away.) The loose hairs the color of chamomile, or our braided knots. Both of our hairs messing up with the wind on our faces at the speed of the night. Her glances, lost inside the walls that remained, from rubble to rubble, searching for some color that does not exist, for some hue alive in appearance.

More or less, never so much, mix a bit of that with the rest as though it were just the preparation of home-made rice pudding, something exclusive, or nothing.

When you are here the contagion is unavoidable. The sensible, irrational. The order, chaos. A scary clarity, without a doubt. Although sometimes the city is also part of the home, and of the thing itself. I dress in the most light-colored clothes to go out on the street. It’s noon and it’s hot, 89 degrees. Crushing, crazy for February. The days that begin with those kinds of signs presage a touch of the unusual, but nothing more happens.

I arrive again. I try to call B: The-cell-that-you-are-calling-is-turned-off-or-outside-the-coverage-area. I use the time to check the Inbox. The milk and the cheese and the bread and the tomato mix in my mouth. I listen to Bebel Gilberto, tanto tempo, the song says. I swallow slowly. The monitor reflects the picture window, with all the wires branching out from the electrical poles. It is almost night again. I go back to the street.

We left Strawberry and Chocolate after more than five beers a piece —B later said at least ten— to get more money and finish up in the first slummy hovel on our way.

On the second block, from inside a car, a bald head sticks out and shouts at us. I vaguely recognize an old friend from secondary school. He is much fatter and I see that he’s the one driving. Inside are two other guys, strangers.

We’re all inside quickly, windows up, passing the joint amid the smoke and the guitar that one of the guys holds. At the top of the lungs, the last hit by Gente D’Zona.

Look at her, look how she sweats, how she strips, she doesn’t know, that my tuba broke…

The lyrics are a mystery. We start to catch the enthusiasm, slowly. B looks at me and I don’t see a desperate expression, I don’t see anything, her reddish eyes go through me and out through the tinted glass, I don’t want to take care of her. I can’t see.

All ages had been boring for B from the beginning, from her mute knowledge of a deserted city, more dead each day. Always in a hurry to sleep again, although even awake it could be said that she slept. Sleep again to lose everything. More nothingness. Emptiness. More nothing.

Between my feet the whiskers, the slow tail, the wet nose. My cat is hungry. Sometimes for love more than for food. I get cold. I pick him up, he weighs a bit, I leave him on the rug. I sit on the floor. I am hungry also.

Anamnesia… Why didn’t you name him Anaximandro, if you wanted something very unusual?

B sleeps.

We got off at a Rapido snackbar in Vedado. The crazy one with the guitar, who was also the one now driving, shouts to everyone from the door that the music had arrived at the cemetery.

The place is full, despite the late hour. I want more beer, I shout also. We take over the first table and we number about six. I ask B if she’s well, if she wants to go to the bathroom. Everyone looks at us like intruders, but they quickly return to their cans. One goes to the bar to ask for beers and demand with screams that they shut off the shrill music on the stereo, to warm up the place.

I go with B. The door to the bathroom does not close, and has a big hole in the middle where the lock should be. There are three men ahead who look like they work in the place. I ask them to let us go in. They let us pass in between guffaws and say something about remuneration, paying them for guarding the door. They look alternately at us and the group, which has taken over a double table, the guy with the guitar has just jumped on a table and to my surprise sings an old ballad from Sancti Spiritus’ troubadours. His voice is more powerful than three stereos together.

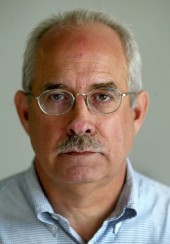

- The Writer Speaks

- Interview by Ernesto Santana

- “ [W]e have become a kind of “civil resuscitators”, no longer satisfied only with commenting or posting the news of violations, but going out to face whatever comes.

- ”

Herminia those phrases that you spilled, they should not be spilled by women.

I tell B to go in and I stay outside guarding. The bald guy comes and brings me a beer and puts two lollypops in my shirt pocket. Strawberry, he says, and leaves again. B opens the door, comes out putting her hair up with a clip, and the gesture slows down, repeats. On her face the lack of expression becomes even more tranquil.

Around the table a new group of five or six women, lured from outside by the music, now sway and sing in a chorus for the one with the guitar. The voltage of their singing keeps rising, toward the roof, and someone comes to ask that we drop the volume. Everyone is having fun, he says and looks like that means him too, but there are neighbors upstairs who could call the police because of the racket.

No one pays any mind. Far from dropping, the voices rise. My beer is finished and I grab the bottle of Legendario rum that is near me. To get used to the guys, these guys, is not so difficult, after all, and I take a deep swig. I pass the bottle to B, who turns it down without looking at me, happy yet removed.

There were days of not going out, of going nowhere, to have no hunger or die from the hunger pangs… days to step on ants, gather leaves, wash our faces and hands in the sour-sweet-salty water of a fountain, throw rice to the most daring birds… days to not-do, nothing, talk to no one, sleep all hours, stay under the shower, under the falling happiness, to land on both feet… days for nothing-at-all.

Days in which it was not possible to wake up, to write letters, comb one’s hair or listen, nothing, anything, cockroaches under the lumber, dust falling on the books, doves crashing into window panes. Days of mosquito netting.

There were days for not-needing, for not putting on faces, of not-having-to-say, nothing, no salutations or farewells to be left on a paper-on-the-table. Days to break down, lose things, find rocks. Days to grow tired before-it-is-time, to grow grouchy-in-vain, answer no doors nor calls nor the pen, nor the desire. Days for not even. Days to go backward, walk more, run up the hill.

On the street, upanddown, we were riding again in the runaway Nissan. I saw that B was beginning to feel sick. I saw how bad she was. More than pale, pasty, chilled.

The bald guy was driving out of control. I shouted to him, above the very loud CD player, to stop so B could throw up. I opened the door and bent her head down by the neck. We were again starting to be in the least expected place. Very difficult situations. It was too much alcohol for B, who got dizzy on two beers. To preserve a minimum of clarity in the face of apparent chaos, a minimum level of organization. That had been my slogan after more than a couple of memorable embarrassments in memorably public places, when large quantities of alcohol still made me throw up.

B looks fragile, not now, always gave the impression of something brittle, far behind her bottomless eyes there was the weakness of a rag doll, of a plant that wants to be abandoned. Protection, company, words with a meaning too strange and not at all desirable. If she needed anything it would be to remain alone, standing, awake, alive. Absorbed in that thought I believed, I think I believed, that I heard the sound of an oriental, sensual, flute, two long notes separated by B’s strange breathing, worrying, broken, nervous. Distant.

She was no longer at my side, I got out of the car as fast as I could, one hand grabbed me hard on the shoulder and, before I knew it, another pulled me from behind and held my face under the nose for all the time in the world, all the time of a human life.

B braids and unbraids her hair in a hypnotic do-undo. The man’s shirt is smudged with dried tooth paste. Crayolas strewn on the bed.

To reach the absurd, in between death and the routine reserved for a dilapidated city, it is necessary to kill all sensibility. Sensibility is hope.

B writes with a green Crayola on the wall, above the bed. She throws the book that she’s copying from on the floor, and lies down, face down. The room is in the red semi-darkness of a small lamp. To persist in the idea of an absolute sadness is chronic. How sterile, I think, this unease is felt by all, while absurd suffering is individual.

My fishbowl-body, lazy-body, becomes endless as it consumes itself, I think. Unproductive waiting for views of sun downs in your neighborhood. Mauve spilling on still humid eyes, all the intense blue turned into premature night.

I could not see who was who well. The next minute I was on the ground, with my legs held by one of them. I managed to keep up the struggle with great difficulty, my throat ripping apart with silent screams. I tried to look where B might be, but they had my head trapped between two arms that my hands were scratching and tearing at as much as possible—at the skin, the cloth, anything within reach. Within this frozen mobility, I could only hear B’s drowned breathing.

No use hoping to hear another sound, her voice made no more sound, disappeared from my ears just as all of her disappeared from my sight. Almost immobile, I felt that they took off my sandals and threw them to the other side of the street. I was never in such an impassive neighborhood. The houses seemed to have been swallowed by the night, holograms substituting for the real ones, the ones that might have been there, at some point, some time. All the windows darkened, no one there had the capacity to come out, to at least look, the whole world appeared to have fallen into the most lethargic of sleeps.

I could not imagine B on top of the hood, with the bald guy on top, or anyone else, I did not want to, despite the sounds, the noisy evidence of the metal, of everyone’s screams. I wished I had been more alone than ever, that it was me under the most disgusting guy, that it was me bursting into that sort of muffled, horrible tremor, that tragic, mimic’s shake.

I wished I had dreamed it, had been able to predict it, had been far and alert, conscious of the inevitable. To be the most skeptical, the most distrusting, the strongest in the world. In some way to have had the opportunity to be prepared, to anticipate the scene, to take a lot of time digesting the most remote possibility, and taking it as a given.

To stomp on even a minimal comparison of statistics, any trust at all on luck eternal. All of the women, the same ones, again and again, subjected to the same violence the same nights, all of them. The ideas were lost like the passive breathing of B, like my hysterical, repressed screams, my attempts to bite the hand that covered my mouth.

How not to sense any groan, any sign of anything. In less than one minute I learned to hold in a strange rage, an unknown fury, some destructive desires. I learned hatred.

If I could have made the least little movement, I would have bashed in the head of that guy with my hands, that guy who probably would have sat two desks away from mine in secondary school, who would have sold me an ice cream last week, who would have been a stretcher-bearer in the hospital where my grandmother died.

The only area that my eyes could see was the part under the car, the red strip that hung from the exhaust and B’s feet, her nails also red. The worst torture was the impotence, the bewildering submission, like in a nightmare, the immediate hopelessness. The turtle trying to go faster while the hare stopped to eat. Lost cause.

Maybe three real minutes had passed, all the time in the world, all the time of a human life, when the first police car illuminated the street with its high beams.

It turned the corner without giving them time to react. Someone probably, after all, had dared to call, to accept just a bit of responsibility amid the silent death of the neighborhood. The profound relief slowly drowned the profound anger. As soon as I felt free I ran to B, knocked down, abandoned by the guy who already had police on top of him when he tried to run.

He released her and B collapsed, fainted, lifeless. On the blacktop she looked like a broken, battered dummy.

One policeman approached. He tried to put me at ease and bother me with stupid questions. He was about 40 and had serious, almost sad eyes. He tried to separate me from B when he saw how badly she was breathing, her translucent skin, but I could not let her go. He left us like that and returned to the patrol car in front of the Nissan. B seemed to revive, saw my feet and held more tightly to me. I could feel her perfectly measured heartbeat, breathe on her rhythm, nervous but gentle. I grew happy, above all else, that she was so dichotomous in the worst of circumstances.

I saw that she was not more fragile than I, maybe my strength was even less. Another police car arrived in two minutes to pick us up, and we learned they had not captured everyone, that they did not know how many there were.

We filled out the complaint at the police station on Zapata, very quickly, without hesitation, without thinking about anything, without considering the danger of those guys on the loose, that they could recognize us at some point, that they would be watching us, without feeling more free than before, without shrinking our burden, more like with something of death. So many others. All of them. Out there. Day after day.

The warmth of B’s hand in mine was more than I could have hoped for at the end of the night, at the end of the fear. That warmth was not at all fictional, it was a warmth that healed, comforted, reconciliated with all things.

We never spoke of that night, never wrote that final period, never closed anything. I think we preferred to wait for a pending conclusion, a time that would be perfect, impossible. I never told B about the sensual sound of the Chinese flute, or the red strip.

Almost at the end we realized how totally absurd it would be to think again about a past that could dissolve itself into the memory, like a lie never uttered, or never revealed. The invention of a paranoid mind. Nothing more.

—Let’s see. Make a “u” with your lips and say “e”, that is the “i-grek”, the Greek “y”, that is how you pronounce the “u” in tortue… Turtulutú-chapeau-pointu ! Repite avec moi…

It smells good, your hair.

—Dis tortue, dors-tu nue ? Say turtle. Do you sleep naked? Say turtle, you sleep naked…

—Ok, stop. Tell me, do you sleep naked?

Edited in English by Joshua Barnes

__________

All facts and characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Los hechos y/o personajes de esta historia son ficticios, cualquier semejanza con la realidad es pura coincidencia.