Some Notes on Translation

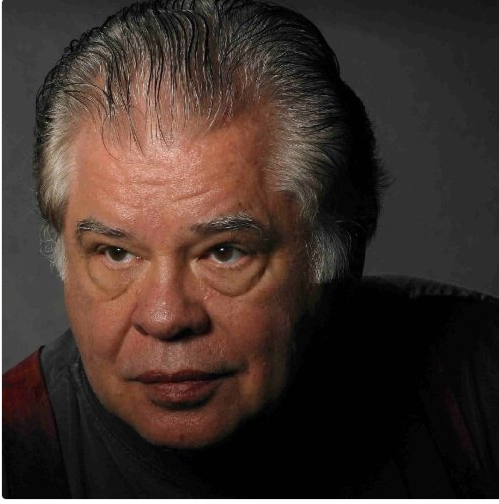

by Clayton Eshleman / December 6, 2016 / No comments

When, at the age of 27, Clayton Eshleman set out to be a poet, he found himself “stuffed,” “blocked,” by an unexamined life, “facing for the first time the sexism, prejudice, rule following and acting out” of what his hometown of Indianapolis, Indiana, had proposed was his identity. He followed an unusual route to develop his own poetic voice: learning Spanish to translate the works of Peruvian poet César Vallejo, a notoriously difficult task for translators who were already fluent in Spanish. Over the years, Eshleman became the foremost translator of Vallejo, and also the poet Aimé Césaire. He has translated works not only from Spanish, but also from French, Hungarian, and, to a lesser extent, Chinese and Czech. He also did become a leading American poet, with a Guggenheim Fellowship, two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Rockefeller Study Center residency in Bellagio, Italy, and other awards including the Landon Translation prize from the Academy of American Poets.

In an interview with Rain Taxi, Eshleman said this in response to a question about the importance of border crossing in poetry and translation. “In regards to civil obligations: given what the American government has been doing throughout the world from the end of World War II on, the American mind, into which news spatters daily, is now, more than ever, a roily swamp, at once chaotic and irrationally organized. The fate of American Indians and African-Americans is entangled with this complex. There is a whole new poetry to be written by Americans that pits our present-day national and international situation against these poisoned historical cores.”

Clayton Eshleman came to read at City of Asylum on November 2, 2016 and gave SampsoniaWay.org his unpublished “Notes on Translation” to share with our readers.

The translator and essayist Eliot Weinberger has written: “As for translation: the dissolution of the translator’s ego is essential if the foreign poem is to enter the language–a bad translation is the insistent voice of the translator.”

In the case of Ben Belitt’s Pablo Neruda translations, we hear the translator-poet’s own mannerisms leaking into and rendering rococo the meaning of the original South American texts. It is as if Belitt is colonizing Neruda’s foreign terrain instead of accommodating himself to the ways in which it differs from his own poetic intentions.

The image of a translator colonizing the foreign terrain of an original text has somber implications, especially in the case of a “first-world” translator working on a “third-world” writer. By adding to, subtracting from, and reinterpreting the original, the translator implies that he knows better than the original text knows, that in effect his mind is superior to its mind. The “native text” becomes raw material for the colonizer-translator to educate and reform in a way that instructs the reader to believe that the foreign poet is aping our literary conventions.

So, how might a translator work to resist ego imposition or, at worst, translational imperialism? There is no such thing as a literal translation of a poem–denotative choices come up in every line. There is a constant process of interpretation going on, regardless of how faithful one attempts to be to the original.

When the original poet is available for questioning, a certain amount of guesswork can be eliminated. When one is translating the great dead, or out of contact with the author, the only indicators come from the text at large, and the way key words can be identified relative to the author’s background. While translation the Martinican Aimé Césaire with Annette Smith, I visited Césaire several times, always with a few pages of specific word questions. Given Césaire’s busy schedule, it was never possible to ask him all the questions that came up in translating him, so many tricky decisions had to be made on the basis of the text itself. As an example: Smith and I occasionally came across the word “anse,” which can be rendered as “bay/cove/creek,” or “basket handle.” Since Césaire’s poetry is very specific to Martinican geography, and since the entire island is pocked with bays and coves (which led to such place-names as Anse Pilot, or Grande Anse d’Arlet), the obvious choice here seemed to be “bay” or “cove.” Yet in the 1969 Berger-Bostock translation of Cesaire’s Notebook of a Return to the Native Land, we find “les Antilles qui ont faim…bourgeonnant d’anses frêle…” translated as “the hungry Antilles…delicately sprouting handles for the market.” Not only has the Surrealist Césaire been falsely surrealized, but the translators have backed up their error by adding an explanation to the reader as to what these “handles” are for. When Smith and I retranslated the Notebook in 1976, we rendered these phrases as “the hungry Antilles…burgeoning with frail coves…”

In the case of César Vallejo, I learned not only to check my work with Peruvians and Spanish language scholars, but to check their suggestions against each other and against the dictionary. I worked to find word-for-word equivalents, not explanatory phrases. I also respected Vallejo’s punctuation, intentional misspellings, line and stanza breaks, and tried to render his obscurity and flatness as well as his clarity and brilliance. An unsympathetic reviewer of my work, John Simon, exclaimed: Eshleman has tried to render every wart of the original!” Which is, in fact, exactly what I had tried to do–to create in English a non-cosmeticized Vallejo.

As the translator scuttles back and forth between the original and the rendering, or in some cases engages in dialogue with a co-translator, a kind of “assimilative space” opens up, in which “influence” may be less contrived and literary when drawing upon masters in one’s own language. Before considering why this may be so, I want to propose a key difference between a poet translating a poet and a scholar translating a poet.

While both engage the myth of Prometheus, seeking to steal some fire from one of the gods to bestow on readers, the poet is also involved in a sub-plot that may, as it were, chain him to a wall. That is, besides making an offering to the reader, the poet-translator is also making an offering to himself–he is stealing fire for his own furnaces at the risk of being overwhelmed–stalemated–by the power he has inducted into his own workings.

But influence through translation is different than influence through reading masters in one’s own tongue. If I am being influenced by Ezra Pound, say, his American is coming directly into my own. You can read my poem and think of Pound. In the case of translation, I am co-creating an American version out of–in the case Césaire–a French text, and if Césaire is to enter my own poetry he must do so via what I have already, as a translator, turned him into. This is, in the long run, very close to being influenced by myself, or by a self I have created to mine. Antonin Artaud once wrote: “I want to initiate myself off myself—not off the dead initiations of others.”

As I see it, the basic challenge is to do two incompatible things at once: an accurate translation and one that is up to the performance level of the original.

All translations are, in varying degrees, specters or emanations. Spectral translations haunt us with the loss of the original; before them, facing the translator’s ego or inabilities, we feel that the original has been sucked into a smaller, less effective size. Like ghosts, such translations painfully remind us to what an extent the dead are absent. Emanational translations, on the other hand, are what can be made of the original poet’s vision; while they are seldom larger than their prototypes, good ones hold their own against the prototype and they bring it across as an injection of fresh poetic character into the literature of the second language.

As someone who has been translating almost since I began to write poetry (in 1957), I have probably been much more influenced by César Vallejo, Aimé Césaire, and Antonin Artaud than I have by any English or American poets. Taking into consideration the curious matter of self-influence that seems to be one of the mixed blessings of poetic translation, I would say that their combined and most potent gift has been one of permission–of giving me permission to say anything that would spur on my quest for authenticity and for constructing an alternative world in language. Here I would keep in mind Vincente Huidobro’s sterling injunction: “Invent new worlds and watch what you say.”

-C.E.