Kwame Dawes and the African Poetry Book Fund

by Annie Piotrowski / August 15, 2014 / 3 Comments

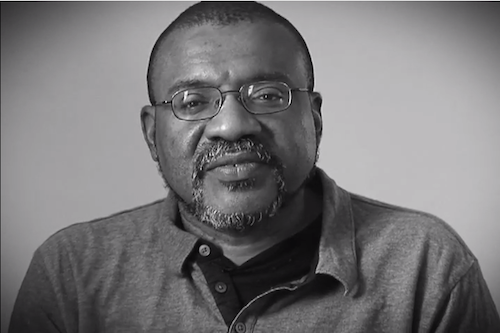

Photo: Youtube user PacUniv.

The Ghanaian-born writer Kwame Dawes is known for his award-winning poetry collections, musical performances, writings on reggae, and journalism. However, his newest project, The African Poetry Book Fund, takes him in a new direction. Created due to the lack of publishing opportunities for African poets, the APBF addresses a silent and informal threat to freedom of expression; namely that given no support or opportunities to formally publish work, a writer’s ability to speak to her community and world is severely threatened.

A platform for works of “great and thrilling beauty,” the African Poetry Book Fund is only one of the ways Dawes engages with the writing community. In the following interview, he speaks about his engagement with African poetry, his childhood love of comics and literature, and the ability of poetry to honor others’ experiences.

What led you to create the African Poetry Book Fund?

While visiting various African countries for festivals and readings during the last five years, I have been reminded of the stark difference between the publishing experiences of African poets and African fiction writers. While the world has engaged with the fiction writers in remarkably positive ways, African poets have few opportunities to publish their work internationally or within their home countries.

Until we established the African Poetry Book Fund, I could not find a publishing press anywhere in the world devoted exclusively to African poetry. Given the rich tradition of poetry in African nations, I thought this was a shame.

I am at a stage in my life where I must work to create change if I see a problem, so I pulled together a group of gifted writers, all of whom have strong connections to Africa. During the African Poetry Initiative’s development, Chris Abani, Matthew Shenoda, Bernardine Evaristo, John Keene and Gabeba Baderoon have been a brilliant team.

What services does the African Poetry Book Fund provide to writers?

We want to see more African poets in print, and to that end, the APBF is focused on a few small but critical projects. Our contests, publishing series, and poetry libraries are focused on supporting poets to produce publishable work. When poets are published, we seek to ensure that they have opportunities to sell their work and enter the circuit of festivals and readings. To accomplish this, we have partnered with Blue Flower Arts, a literary agency, to represent our poets. Additionally, APBF’s website and mailing list connects writers to publishing opportunities.

Some folks have suggested that our focus on publishing excludes African poetry’s rich oral and performance tradition. This is true only in the sense that we are focused on what we believe is necessary and achievable. Though tours, spoken word events, podcasts, and video-casts are valuable, they are not part of our work unless they aid in the publishing effort.

What do you think causes the difference in opportunities for African fiction and African poetry? Is that any different than the place that poetry holds in the US?

In African countries, small presses sometimes publish the poetry from their community members, but like in many parts of the world, publishers do not believe that poetry can be a viable enterprise. Apart from that, for complicated and discouraging reasons, we mainly celebrate African writing that is published by African writers in the developed world. Their publishers may be interested in fiction because of its commercial value and expository nature— explaining the continent, if you will.

In the U.S. and the U.K., subsidies and the economics of scale allow several presses to devote themselves exclusively to poetry. Due to this small press movement, along with the major poetry prizes each year, published poetry exists and in some instances thrives.

However, these presses are not interested in African poetry given its uncertain commercial value. For example, our team signed an agreement with one of the USA’s leading poetry presses for an exciting anthology of contemporary African poetry. Before we arrived at the contract stage, the publishers said that it would be impossible to raise the funds for a book of that nature.

During your development as a poet, were you ever in a place where you felt that your ability to speak was threatened?

I have felt threatened, but my experiences were minor compared to the censorship faced by other writers, and I don’t make a great to-do about my struggles. Growing up in Jamaica in the 1970s and 1980s, my peers and I were aware that our political affiliation, whether real or imagined, could seriously impact our freedom of speech and action. However, those threats did not stop people from speaking out. During that time, I was particularly inspired by reggae artists. They taught me invention, daring and a serious commitment to the quest for honesty.

In my later life, I have felt threatened, but mostly from my own insecurities. In my writing and community work, I often deal with censorship that comes out of societal norms. The self-imposed restraints that come from the pain of being attacked as a liar and our fear of loved ones’ responses to our writing. The great fatigue of constantly having to explain ourselves.

Yet I believe that these types of silence are the first condition of art. To answer them, we must find the wisdom and power to write into our silence.

The African Poetry Initiative is just one of your many community projects. What has most influenced your dedication to service?

I believe that I can best serve the community as an editor, organizer and teacher. I learned these skills from my family and the countries of my childhood, Ghana and Jamaica. I was born in Ghana and moved to Jamaica in the 1970s, so I have memories of growing up in Ghana in the 1960s, a time of great change, turmoil and excitement.

I come from a family of artists—my father, a writer, and my mother, a visual artist. My father advocated for writers, artists, and cultural organizations. He was also a teacher, and, combined with my mother’s years as a social worker, it should be clear why all of my siblings are active in social service.

How do you begin your community projects?

During my projects, I first explore a situation, and afterwards, I try to tell its story. Sometimes different types of art emerge from that work, but the initial impulse is always the same—an effort to understand and to report on a subject that demands attention. For example, my Live Hope Love project was a journalistic effort to report on the state of HIV/AIDS in Jamaica. I am currently working on a follow- up project, SHAME, to explore the Jamaican church’s response to HIV/AIDS.

The African Poetry Book Fund is slightly different. It is a service to writers similar to my work with the Calabash International Book Festival and Cave Canem, an organization for African American poets.

Alongside the African Poetry Book Fund, you are also building libraries in five African countries. What books will go into the African libraries that you are helping to create? Who are they for?

The libraries are slated to open in September. Early this summer, we shipped around four hundred books, solicited by the APBF and Prairie Schooner, to The Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda and Botswana.

The reading libraries are a resource for poets in these countries to have access to contemporary poetry books and journals. We partner with organizations and individuals in these countries to set up these libraries, adding them to existing public libraries and arts organization offices. We also have volunteer consultants who will develop solid outreach programs and ensure that the libraries are used as broadly as possible.

What kinds of books did you read as a child?

Growing up in Ghana, my father was dead set against having a television. Of course we would go to our neighbors to watch TV, but at home we had to find ways to entertain ourselves. We had our share of toys, but, most importantly, my father did not scrimp on books. I don’t recall a time when I did not read, both books that were supposed to be good for me and supposed to be bad for me.

We read popular comics like Archie, Marvel, the funnies, The Adventures of Tintin, Asterix, and then all of Enid Blyton, the Hardy Boys, the Bobsey Twins, and the plethora of books about British boarding school, and then more literary fare as we got older. However, it was a revelation when I started to read works that had people who looked like me in their pages. I suspect I did not start to seriously read poetry until we moved to Jamaica when I was in high school.

What drives you to write poetry? Is it what drives you to work with different communities?

In all my work, the defining principle is to do justice to experience.

I write because of — and also inside of and outside of—the things that engage me as a human being. I tell my writing students that as writers, they should not feel especially gifted with spiritual insight. I tell them them that ideas are a dime a dozen, and that many people who are not writers have some of the most astounding ideas.

The difference between them and us writers is simple: we write. We write because we have been trained to write and have been affirmed as writers. Whether it feeds an internal pathology, or we are trying to seduce people, it may be all that we know how to do.

The bottom line is that we write. We might as well get good at it so that we can use our words to articulate what others feel and experience.

This is the first year that you’ve published titles from The African Poetry Book Series. From the writers that you’ve published, are there any particular verses or poetic moments that stick in your mind?

I wouldn’t quote passages of poetry from the collections we have published in this first year, and anyway, I am hopeless at memorizing, but I will say that the Promise of Hope: New and Selected Poems by Kofi Awoonor is a book that everybody should have in their home.

Clifton Gachagua, Kenyan author of Madman of Kilifi, is a startling new voice in the poetry world. The poets that we publish in the New Generations chapbook series—TJ Dema, Tsitsi Jaji, Len Verwey, Nick Makoha, Warsan Shire, and Ladan Osman—are really not “discoveries” since they have long established themselves as powerful poetic voices both in their countries and internationally. We are honored to publish them via the African Poetry Book Fund through our partnership with The University of Nebraska Press, Amalion Books in Senegal, and, of course, Prairie Schooner.

Their books are full of music as varied as the continent of Africa. That is the great and thrilling beauty of the matter.

3 Comments on "Kwame Dawes and the African Poetry Book Fund"

Je suis un écrivain congolais, je suis selectionné pour participer à

la journée du manuscrit francophonie où mon livre”enfants de la rue,

pour quel avenir en afrique?”, il est demandé à chacun de s’y rendre

pour recevoir son livre publié en version papier, à la soirée du 24

Octobre à Dakar, où tous les auteurs doivent être présents.Je ne suis

pas en mesure d’assurer mon billet d’avion brazzaville-dakar, peut

être le séjour.Pour cela je vous écris si au niveau de votre

organisation, une telle aide est possible.

contactez si possible:

http://www.leseditionsdunet.com

http://www.lajourneedumanuscrit.com

guy aurélien biantsissila

auteur congolais

00242.055261176

bp 12052 brazzaville

Trackbacks for this post