Unfinished Business by Erick Mota

by Sampsonia Way / September 6, 2013 / 1 Comment

Translated by Karen González

Nights in Old Havana are always loud. Each carrier rocket shakes the old rocks of the almost sunken buildings. The canals with black waters, which run across the archaic streets, light up with the gleam of oxygen and hydrogen in combustion. The water, mixed with petroleum from the old Soviet cargo boats, vibrates and flutters with every take-off. Like gigantic flares, the Protons-II rockets light up the old parts of the city with every departure. They bruise the sky of Autonomous Havana and disappear into the cosmos monopolized by the Russians.

Up there they have the space stations, the satellites with nuclear warheads, the servers for the Global Neural Network, the whole Russian way of life, as those balseros(i) in Florida say. Down here illegal immigrants sleep in the corridors at Almejeira hospital and work on the platforms in Underguater for four kopeks. All of them with the hope of getting into one of those rockets that will take them to the Romanenko station. Or any other. An entire life of sacrifice just to be like one of the Russians. Another tovarish.

- Erick Mota

- He has published the fiction books: “Bajo Presión” (Gente Nueva, 2008), “Algunos recuerdos que valen la pena” (Abril, 2010), “La Habana Underguater” (Atom Press, 2010) and “Ojos de cesio radiactivo” (Red EDICIONES SL, 2012).

- Erick Mota is a kind of chronicler of our thousand and one post-Fidel fossil futures. Entertaining, funny, relying on pure action, from which emanates however a sad reflection on the present of Cuba.

- Read more…

- The Writer Speaks

- Interview by Cristina Jurado Marcos.

- “We are so close to our reality that trees don´t allow us to see the forest. When we depart from a re-written story, and if we add elements of our actual reality, then we can reflect properly about our real lives.

- ”

- Karen González

- Born in Holguin, Cuba. Migrated to the United States in 2006.

Attended the University of Florida, where she got her Bachelor’s Degree in International Studies. Karen speaks fluently English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Email her or Follow her on Twitter

But you know very well that that, more than a dream, is a fantasy. That the Russians never treat anyone like an equal. That you end up being another immigrant in another place. Another foreigner in a strange land.

You, too, became a victim of that fantasy. You lived in a city in chaos, after a hurricane sank everything and forced everybody to start shooting each other. You went up there and you never looked back.

Now the chaos is organized. There are abakuas(ii) pacifying Old Alamar, Santeros(iii) in Downtown, and Babalawos(iv) in Vedado. Investors of religious corporations in Miramar, and the FULHA that watches over the old fortress in La Cabaña. FULHA: The emergent force that tried to make use of the army, police, and government, but in the end it just ended up becoming another force fighting in the midst of anarchy. Nobody rules over Havana. There is no order in this city. But, at least, there’s less chaos.

And you came back. Not looking for order or chaos. You came back because you had no choice. Because there is no better place to be than home. And Havana, even if it’s Hell, is your home.

You came down in one of the last landing capsules left. You fell in Puertohabana Bay thanks to the good aim of your Russians tovarish. You were rescued by the Marine Cost Guard. Last time you heard anything about them, they were a FULHA special unit. Now, who knows.

The FMC speedboat zigzagged through the street of Old Sunken Havana until it arrived at the Cathedral. There, in the space station pier, they left you in the hands of some guys from Russian customs. They finished the papers and offered a boat to Underguater or Vedado. You said no.

You are now legal in Autonomous Havana. When you left, you were a mere Cuban citizen. Now, you have a Russian passport that allows you to enter and leave this city-State that you barely recognize anymore.

You look at the ocean, the sunken buildings, the layer of petroleum that moves in unison with the water.

‒Should I call you a cab, comrade?

‒A boatman that will take me to Sunken Cayo Hueso will be enough ‒you say while you give a ruble to the employee of the space station that rests over the old Cathedral‒, and don’t call me comrade. Please.

You take a twenty pesos motor boat. You go through the Underguater’s stretch of canals until you get to Sunken Cayo Hueso. You look for an address. You find it. You give the boatman a ruble. He says he doesn’t have change. You reply in a bad mood that you don’t need it.

You take the half-sunken stairs up the building. The houses that are still habitable begin after the third floor. You remember this place. Too well.

Going up the stairs there are five boys. They’re wearing t-shirts, they carry revolvers around their waists, and they smell like cheap vodka. Kids from the neighborhood that dream of becoming famous aseres one day: Bodyguards of famous porn stars from the studios at Old UCI or working for the santeros in Downtown Havana. They all want to be successful and become rich in the most mediocre and small-minded way possible.

You realize the neighborhood has not changed at all. You walk by them without paying much attention. One of them, the one who seems to be the leader, cuts in front of you.

‒To pass by here, you have to pay a toll, dude.

‒And why should I have to pay you, dude? I don’t see you doing anything worth a single kopek.

‒The problem is what I’m gonna do to you if you don’t pay me.

The others laugh. To you it is just returning to the old neighborhood.

‒Does your mom know you’re here? You better go back home, dude. Before you hurt yourself with that gun.

The boy loses his composure. He’s red in the face with anger. He yells, pushes you, aims his gun at you. Just what you want. You were always good at making people lose control.

You grab his wrist, you twist it. There is a shot and the bullet finds its target in the chest of another boy. In one stroke you break his elbow. The scream makes the others freeze. The boy bends in pain. With tenderness you take the gun and let down a blow with the handle into his head. The body falls unconsciously in the middle of a blood pool.

‒I already told you ‒you throw the gun away‒. Go back to your houses. This isn’t for you.

And you keep going up the stairs that leave you short of breath. You are old and used to the easy lifestyle of the orbit. You can’t fight properly and go up four floors at the same time. The neighborhood hasn’t changed, but you have.

When you finally arrive at the door, you’re exhausted. You are almost too out of breath to call out. You don’t want to do it either. You respond to the perverted need to suffer for those things. Especially for the past. But you have thought about that before. If you were able to control your instincts, you would have stayed in space. Living comfortably, with the Russians in zero gravity.

You knock on the door. She opens. Secretly, you were hoping she wouldn’t be there, or that she wouldn’t want to let you in.

-It’s you. I never thought you’d come back.

-I never I thought I would. But here I am.

-Yes, here you are. That much I can tell.

She remains in an awkward silence for a few seconds. Then she walks away toward the window. She has no intention of closing the door in your face or yelling at you until you leave. She does not seem to have any intention of asking you to come in either. It’s a step forward.

‒You don’t belong here anymore ‒she says.

‒You never stop belonging to Underguater.

You walk into the small room. A smeared stove attempts to warm up some old pots filled with food. The bathroom is as small as those in the space station. It’s open, dirty, and lacks tiles. Next to the window, she gazes into the sea. You get closer. What she is gazing upon is not the interior lake of Havana. It’s the real ocean that expands in front of the city like a blue desert.

‒The neighborhood is the same as when I left –you say more to break the ice than to start conversation‒. You are too.

‒In Underguater nothing changes. Ever. But you have changed. You look more… Russian.

‒Have you heard anything from him?

‒Who? Ricardo Miguel…? I don’t understand why you ask me about him. After you went up there, he left for the Malayan-Korean-Japanese complex. You must know more about him than I do.

‒He doesn’t write?

‒Neither do you.

‒He doesn’t send anything for the boy either?

‒Did you ever send anything? My son is not any of your business. Yours or his.

‒I have to know. Even he should know too.

‒No.

‒No, what?

‒Just no. It’s easy to go to orbit with the Russians or to Asia with the non-Catholic corporations. Let time go by and come back to ask: Is your son mine or his? Like that makes a difference. Like that’s going to pay for all I have been through, alone, with a child in the middle of this nest of aseres. I had to go through plenty of sacrifices to feed him, educate him, make sure he goes beyond the limited horizon of everyone around here. And now that he’s grown up, now that he did not become an asere or a hacker, now that he has a decent job in the Ifá Navy… You land in Havana just to ask if he’s yours! What if I tell you he is? You’re going to worry about him now? You’re going to take him to live in a luxurious orbital station with the Russians…? And if I tell you he is Ricardo Miguel’s, what will you do? You will go to the sunken plaza at the Cathedral, go to the space station, board a rocket, and we will never see you again. Will you have the courage to find Ricardo Miguel with one of the espionage satellites over Asia? Would you have the courage to tell him that my son is also his? No. I won’t say anything to either of you. My son is not from any of you two. He is mine and that’s it.

‒But one of us is the father.

‒Like Ricardo Miguel would say: The mathematical probability that either of you is the father is one over two. Of course one of you is the father. But knowing it doesn’t change anything for him.

You know very well that she won’t tell you anything. That she doesn’t care that the Russians don’t treat orbital immigrants as equals. That the luxury and low gravity come at a price. She doesn’t care that Ricardo Miguel is little more than a slave programming zeros and ones in a bunker in Pyongyang. In her eyes there is only Underguater. The troubles she’s had to go through to raise a son in the middle of a warzone. Her and that ocean she had always wanted to cross. Neither you nor Ricardo Miguel ever wanted to get out of here. You wanted to be the toughest asere in Downtown Havana. Ricardo Miguel, the best hacker. Your horizons never reached that far. But there was her.

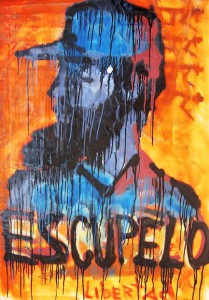

That girl who spoke of the tomb of Che in Autonomous Santa Clara. Of the special troops that held honor guards with their black uniforms. Of the devoted who arrived there walking all the way from Autonomous Santiago following the Invasion Route. The sacred path of Guevara. She also spoke of the sanctuary at La Higuera, in Bolivia, where there was the Firing Squad Chapel. The place where the Holy Insurgent had died. She spoke of the towers at the New Vatican in Dublin, of the battleships of the desert that guarded the oil wells in Saudi Israel. Of the Kremlin, in Old Russia, of the corporate islands in the oceans of China. Of the Russian space stations that patrolled everything from the sky.

And she filled their heads with dreams. And the horizon at the edge of the ocean grew and grew. And you two had no choice but to love her. And the baby arrived. And the realization that you both had loved her in a sick and selfish way. Insufficient to share her. And you fought. And you both felt ashamed of fighting in front of her. Of endangering the life of the child out of pure and simple selfishness. And you left. And he left. But she had to stay.

Nobody gives a working contract in the corporate complexes to a woman with a small child. No guerrilla community would accept a member with a baby in her arms. She had to stay. And keep gazing into the horizon, more with the heart than with the eyes.

You know she will never tell you. You assume Ricardo Miguel has tried in vain too. That is why he will never come back. But you have to know. You don’t want to keep playing the Russian lapdog. You don’t want to keep looking down at Havana. You care about this city, half collapsing, you care about its dirty waters that run through the sunken streets, you even care about the FULHA helicopters that fly over the buildings, like bad omen birds. And, above everything else, you want to look into the eyes of that young boy who calls the woman you once loved “mother.” To know if his eyes are yours or his. No matter the consequences. You just have to know.

You look at the clock. It’s late, you have waited long enough. The boy will soon come back home. She doesn’t have to say anything. You will know just by looking at him.

There are footsteps on the stairs. You remember you never closed the door. It was a clever maneuver to see him as soon as he came upstairs.

Several people appear on the threshold. There are three of the boys with whom you fought downstairs. They come with two other guys. Tall, strong, and with bulletproof vests. Professional aseres. Possibly uncles or father of the one you killed. Or of the one whose arm you broke. This neighborhood will never change. And for the first time in many years you feel happy. You are at home. You can take care of this before the boy gets back.

‒Come and show us how tough you are now! ‒one of the boys says‒. Try to break his arm, come on.

‒Whose, his? ‒you point at one of the aseres as you walk toward the door.

One of them takes out a gun. It is a CZ. Your instructors trained you to call it Česká Zbrojovka. But in Havana it has always been called CZ and you are not in orbit anymore.

You jump on top of the asere before he even draws it. You two wrestle. He tries to take his gun. You apply a chokehold and you use him as a shield. The shot from the CZ lands in the vest of the asere. You break the neck of your hostage and you take his gun.

You shoot the Makarov before the CZ. A clean shot to the forehead. One of the boys jumps over you and makes you lower your gun. You feel the cold of the steel on your ribs. You let go of the gun, you hit the neck of the boy. You move between the other two. Gravity upsets you and the stab hurts. You hit them with anger. You break their bones, fracture their necks. You kill them in a simple yet poorly efficient manner. Your Russian instructors of martial arts would reprehend you if they saw you. But they are not here. Gravity makes you dizzy, you hit the ground.

‒You’re old. Too many years of the good life have made you slow –she says bending down over you.

You feel her hands trying to heal the wound. You also feel the blood flowing.

‒You should have never come back.

You hear footsteps on the stairs. It must be him. It’s almost certain that it is him.

You don’t have the strength to turn your head. You make one last effort. You look, but everything is dark. One last whirl of dizziness makes you feel like a Proton-II knocked out of orbit.

‒Mom, what happened! Are you okay?

You get to hear it. But you can’t see anything anymore. Around you everything is turning blurrier and blurrier.

__________

(i) Balseros: slang term used for Cubans who cross the Gulf of Mexico in a raft or boat to get to Cuba from the US.

(ii) Abakuas: member of Afro-Cuban religious fraternity.

(iii) Santeros: practitioners of Santeria, an Afro-Cuban religion that syncretizes Yoruba religion with Roman Catholicism.

(iv) Babalawo: a high priest of Ifá in the Yoruba religion.

Edited in English by Joshua Barnes

__________

All facts and characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Los hechos y/o personajes de esta historia son ficticios, cualquier semejanza con la realidad es pura coincidencia.

Leer en español

__________

One Comment on "Unfinished Business by Erick Mota"

I ran across your blog website on google and view a few of your current early articles. Continue to keep up the very good operate. I just extra up your RSS feed to our MSN News Reader. In search of forward to studying more by you later on!…