The Bonsai Poet of Bangladesh

by Caitlyn Christensen translated by Nandini Mandal / May 2, 2016 / 2 Comments

Tuhin Das, current ICORN writer-in-residence of City of Asylum in Pittsburgh, stands in front of Burma House on Sampsonia Way. Photo by Renee Rosensteel. All rights reserved.

Tuhin Das says, “If I return to Bangladesh, I will be killed.” Since 2013, he has been the target of fundamentalist groups who have murdered freethinking bloggers and editors, often in public and in broad daylight. In Bangladesh, writers are being persecuted under the Information and Technology Communication Law. Instead of protecting Tuhin, the police collected and examined his writings for anti-Islamist statements to use against him. To save his own life, he had no choice but to go into hiding and find a way out of Bangladesh.

Tuhin is a poet who has authored seven poetry collections. He is the son and brother of women who have faced gender-based discrimination. He is a lover of his nation’s literary culture. He comes from Barisal, a city in south-central Bangladesh that has produced many other freethinkers like him. In several ways, his life—personal and professional—has coincided with the rise of fundamentalism in Bangladesh. In the following interview, he talks about all these facets of his life.

Tuhin Das is the current ICORN writer-in-residence of City of Asylum in Pittsburgh.

How did your upbringing encourage your development as a writer?

My mother always encouraged my writing, and my father would regularly supply us with books, magazines, storybooks, and other books of interest. I have an older sister and she loved to write. Our parents encouraged this habit. My sister loves singing and I learned how to play the tabla, a kind of Indian drums.

As I child I wrote parodies of the poems I read in my textbooks, full of humor and sometimes satire. I started writing because I loved to write, and seeing some of my poetry published in children’s sections of magazines encouraged me to write more. In the 6th and 7th grades, I felt that I wanted to share certain thoughts and feelings with people. I realized I wanted to continue writing to express myself.

How did witnessing your mother’s and sister’s gender-based discrimination impact your political awareness?

When I was growing up, my mom, who was a working lady, endured catcalls on her commute, especially because of her attire. Married Hindu women wear special red and white bangles, and a red bindi on their foreheads signifying they are married. Her appearance attracted harassing remarks that were seemingly harmless, but did have an effect.

Given the fact that it is a patriarchal society, working women are not always seen as equal, even though half of the population of Bangladesh is women, and there is a huge population of working women. However there are two opinions that dominate society: one is the religious fundamentalist groups, who feel that women should not work or go outside the house. The other is patriarchal thinking that wants to control women by not giving them any economic independence. When I was younger, people would comment on my working mother, but it wasn’t as bad or ugly or vulgar as it has become now, where fundamentalists are using religion as a tool to suppress others.

We need the education of women on a mass scale. Not just education in fine arts and literature, but education on sex as well. As for the sexual harassment, young teenagers are making these lewd comments because they are looking at women as objects as a result of repression.

Image by Nathan Deron.

Your family is of a Hindu minority background. What was your experience of tensions between religious groups growing up?

I am a Bengali and Bangladeshi first. Some people want to define me by my religion, but I want to be known by my culture, which is Bengali. When I was defined as a Hindu, it would affect me a lot because I always liked to think of myself as a Bengali. Given the fact that Bengalis have a very old heritage of being a culturally rich, secular and non-communal society, it was deeply rooted inside me that I am a Bengali first. I have always wished for a renaissance where religion would not define our culture, and a person’s identity is not defined by his or her religious beliefs. Someone needed to object to that perspective, and so I wrote about the need for more open and secular thinking around me.

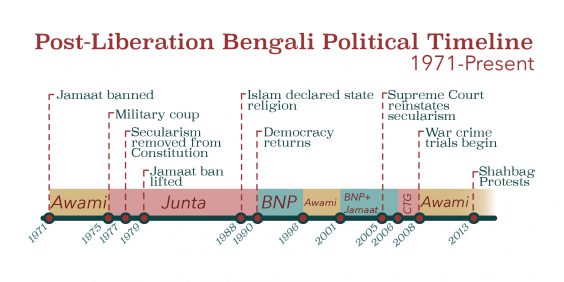

I was born in 1985. In 1988, the authorities declared that Islam was the state religion. As I was growing up in the ‘90s, I found out that people were slowly getting blinded by religion. Somewhere, deep inside, people around me were changing.

When I went to school, even though I was at the top of my class, I felt that there was an unseen wall between me and my classmates. As children, at least every week my sister or I would have a bandage on our heads from the other children, who would throw rocks at us or push us. During cricket matches, the game would suddenly end whenever it came my turn to bat. When other children heard that I was Hindu, they would say, “You will go back to India when you grow up.”

When I complained to my mother, most of the time she would tell me that it is okay. The other children don’t understand what they’re doing. Ignore it. She would also say that there was no other solution because they were from the majority. My father was more introverted. He had experienced the same discrimination growing up and tolerated it quietly, but believed one day it would end.

What hurt me most was when people would say, “You are a Hindu. Your parents are both employed, and they must be sending money to India. You will also go there one day. You are India’s spy.” In 1947, during the Partition, a lot of Hindus had to migrate because of the communal rights that happened there. Though it was very difficult, my grandfather and my father chose to stay in Bangladesh because it was the land where they were born. My father even fought in the war against Pakistan. It’s extremely painful to be treated as outsiders when there is so much that my family has done for Bangladesh. My family and I felt like since we were born there, we were citizens and shared equal rights with everyone. But suddenly it became clear that we were unwelcome. This is my mother’s land, and my own land, but they treated me like I don’t belong, we are outsiders, and not just that, but spies too.

I used to show all of my columns protesting discriminatory religious treatment to my father. He would say, “Continue writing, continue with your protest because one day it might work. Who knows? If you don’t protest now your children might be victims too.”

Graphic by Nathan Deron.

Those editorial columns were published in your magazines. You started your first one, The Wild, in 2000. What led you to create The Wild?

The Wild was a magazine I began as a part of the Little Magazine Movement, created as an alternative to the numerous, traditional magazines and literary publications in Bangladesh. The non-traditional ideas and liberal concepts that were not printed by the regular magazines would find their voices in these “little magazines,” which would often have one editor-cum-publisher. I became acquainted with the movement in 2000, and that same year I started publishing and editing my own little magazine called Aronnak, or The Wild.

I started editing the magazine to give opportunities to emerging writers and new and unheard writers. I mostly had writers from Bangladesh and West Bengal’s progressive movement. Bangladeshi writers submitted different poems and essays expressing their own opinions against communalism, and especially state-sponsored, politics-based religion.

In addition to giving voice to new writers, I wanted to write against injustice, and existing wrongdoings, like discrimination against women and minorities. We wrote against discriminatory decisions and opinions and expressed ourselves freely. Out of the six issues that were released in the first year, I wrote editorial columns in four of them. I expressed my thoughts against the war criminals and the ones who persecuted minorities.

In 2001, minority groups experienced persecution when the Bangladeshi National Party and the Jamaat-e-Islami Party came into power and formed a coalition government. I wrote editorials in February, April, June and August, protesting against the measures they had taken against the minority communities.

In response to the editorials, I received mixed reactions from a lot of my readers. Many of them advised me not to write on these issues as they were afraid that I would be persecuted. Some of the writers protested, saying that they would not provide any of their works to my magazine if I continued writing on sensitive issues like these. However, most went ahead and continued submitting their work to The Wild.

Eventually I became irregular in my editorials, caught up in my own creative writing. At one point I was editing nine magazines, and my writing was being published in various magazines in West Bengal, in India, and Bangladesh.

I did not realize that protesting against persecution, religious thinking and narrow-mindedness would one day be the reason that I would have to flee my country.

Besides being an editor, you are also an accomplished creative writer, named among the top ten young writers from Bangladesh’s “Millennium generation” of poets. How did your editorial work and blogging influence your creative work?

Most people are not now writing politically-based poetry the way they did in the ’70s or the ’80s. They are afraid that if they do and they step out of their house, they might not come back again. Even if they are writing about politics, they hide their references behind metaphors and other disguises. I consciously keep my poetry away from political references.

My editorial views affect my creativity minutely, but I wrote about political issues more freely in my editorial columns. At the time, much of the poetry being written by some of the poets and writers would use nomenclature or terminologies that were a little biased towards an Islamist point of view. I wrote against the use of those, and asked, “Why are we giving a religious color to the poetry?” That was my main concern, and was also what I wrote about in many of my editorial columns. It was then that I started writing poetry that was void of any kind of religious references or any symbols that could link my poetry to a particular religion.

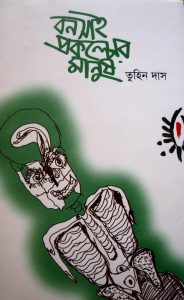

Especially in my first collection of poetry, Bonsai People (2009), I tried to keep everything free of religious references. In that collection, I used the bonsai as a comparison to the people who were around me at that time. It was as if humans were becoming more like the bonsai, a plant restricted from growing to its full height and structure. I felt that their day-to-day living, their connection to nature, their feelings, their emotions, their expressions, were all being shaped by others or they were self-censoring. They wouldn’t express openly, wouldn’t grow out. I wanted to highlight the soft nuances, the emotions, the very feelings that we express. It is those beautiful feelings—the ethos, pathos, that we all have in us—that were being slowly lost.

We poets think that the reader, him or herself, is a poem. When he or she thinks about the poem and expresses their opinions is when the poetry becomes successful. People found the concept of similarities between humans and the bonsai really interesting, and the book was very well received. In fact, I was often referred to as the Bonsai. At that point, many readers avoided poetry, especially Bengali poetry, because they thought, “It is so complex, we do not understand poetry.” On the book’s inner jacket, I wrote that it is not poetry that is complex, it is humans who are becoming more complex. Everybody is so disturbed inside, and peace between the inner self and one’s surroundings is lacking. In their race against time, people do not seem to have the patience anymore to relax and understand poetry. That human complexity was reflected in my writing.

I did not realize that protesting against persecution, religious thinking and narrow-mindedness would one day be the reason that I would have to flee my country.

Who are your literary influences?

In the modern era, the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore has more or less influenced Bengalis around the world. I am strongly influenced by writers who come from Barisal, where I am from, like the poet Jibanananda Das. In ’47 he moved to Calcutta, India. His poetry influenced me, but more than his poetry he had a lot of frustrations and depressing circumstances in his life. He died in an accident, and his solitude, his loneliness, depression, and the process of his poetry affected me.

Another of my influences is Abul Hasan, who would write very openly in the ’60s. He is considered one of the greatest poets of Bangladesh.

In article writing and in other literary editorial columns, I was influenced by Humayun Azad. Humayun Azad was a freethinking writer. He was attacked by fundamentalists for writing on the same topics I do. He died in Germany.

Another influence is the philosopher Aroj Ali Matubbar. Outside of Bangladesh he is considered to be one of the greatest philosophers. He was self-taught, a farmer, but very open minded and liberal in his thoughts. Of course, because of that he was also disliked.

Bazlur Rahman B.A.B.T., a freethinker, is another influence. The name of his book is Questions.

Graphic by Nathan Deron.

You have written seven poetry collections in all, and finished the last one, Timber Face, in February 2016, while you were in hiding. How did that book compare to your previous work?

Everything was done through emails, and I sent the manuscript to my publisher in Dhaka in February 2016. Like my previous books, in Timber Face I talked about relationships. However, in this one I gradually started using a simpler form to express my thoughts.

When I started writing, I had an obsession with using complex Bengali words. Slowly I started thinking that if I made my poetry more simplified, then maybe more people would understand it. I tried to convey the same message, the same thoughts that I had in previous work, but I used a simpler and more fluid vocabulary.

How has editing and publishing in Bangladesh changed in the 16 years since your career began?

We are seeing the effects of what started in 1974 when Daud Haider became the first writer to have to flee Bangladesh because of his poetry criticizing religion. Others include Taslima Nasrin, who wrote against women being persecuted, discriminated against, and tortured in her book called Lajja. She has lived in exile since 1994. There was also the poet Shamsur Rahman, an excellent and well-respected writer in the Bengali literary world, who faced a lot of backlash because of his writings on Bengali heritage, background.

Initially there were fewer restrictions on literary publishing; it could be done by anyone. A publisher could even be the editor of his own magazine, or an editor could start his own publication company. Anybody could write anything, could publish any books. There were a lot of books being read.

However, when I started writing in the 2000s, writing on a blog or a website was not very popular. In fact it was unheard of. We didn’t know there were so many voices writing — or maybe there weren’t so voices writing. Looking back now, I find that there are more people voicing their thoughts many compared to when I first started writing, especially from the younger generation, and their voices are being heard.

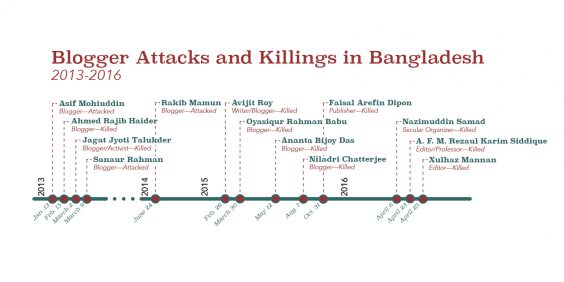

In 2004, Humayun Azad was attacked for his progressive thinking. He had received a scholarship from PEN International in Germany, but died while pursuing his research. Between 2013 and April 2016, 16 bloggers, atheists, editors, activists, publishers, professors and writers have been murdered because of their publishing.

But now, as I am sitting here and looking back, I think that I am successful, at least with what I started. We know that nobody can silence our pen. This fight that we started against non-secular thinking will go on. We have a very thriving culture and a longstanding tradition of secular thinking, which we will protect under all circumstances. As writers, that is our main concern.

People are afraid that if they step out of their house, they might not come back again.

What issues did you write about on your blog and how were your posts received?

I wrote stories that reflected on the persecution of minorities. I wrote about fundamentalists misusing the mosques’ infrastructure to organize attacks on minorities. For example, they used the mosques’ loudspeakers to make public announcements calling on people to destroy dargahs, Islamic shrines, or burn homes in the minority community. As the message comes from the mosques, people do not defy it.

I have also written on topics such as warrantless arrests made under clause 57 of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act. Under this law, any comment that is perceived as heresy can lead to an arrest.

In Bangladesh, people are arrested for “criticizing Islam.” If somebody is teaching science and they are talking about evolution or Darwin’s theory, whatever they teach can be twisted and lead to a crowd protesting against their teachings. Arrests could be made against the science teacher without any fair or neutral investigation.

Young people received many of the blog posts favorably, although when I posted on Facebook I received a lot of backlash from general readers.

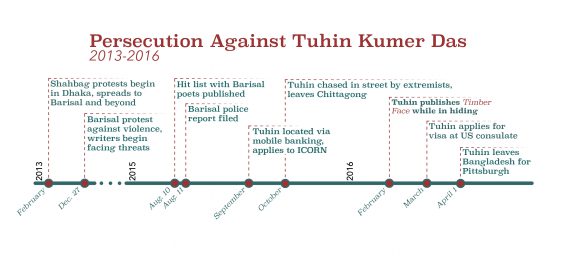

You became involved in the Shahbag Protests in 2013. What was it like to be a part of that movement?

In 2013, the movement was basically initiated when a handful of online activist bloggers posted that we should all meet at Shahbag Square in Dhaka and protest for a harsher sentence against Abdul Quader Mollah, who was convicted for war crimes by the International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh. It was meant to be a small gathering of people. Somehow, after one day it grew to be hundreds of protesters, then thousands, and soon it was waves of people, including a huge number of intellectuals. We wanted justice against the criminals, justice on behalf of victims of rape and those who lost their lives. The protest spread outwards from Dhaka and it came to Barisal, my hometown, where I became more involved and joined the candlelight vigils and the marches, showed placards, chanted slogans, and read my poetry at public gatherings. Some of us involved in the protests fought against the discrimination of women, some against the war crimes, and my main goal was to speak against religious persecution and for a more secular Bangladesh.

The whole movement itself was very exhilarating for the younger generation like myself. We were not alive in the ‘70s, but we heard about the war of ’71 and knew how we had won our freedom and the Bangladeshi nation had been born. We had heard stories of the war, the struggles, and the crimes that occurred. With all of these people coming together, we felt we were a part of something historical, fighting a second liberation war. The movement gathered momentum and the crowd was of a Himalayan proportion.

As a result of your involvement with the protests, your name was included on a hit list, along with other poets and writers involved in the movement. Eventually, this led to threats against your life. Why were you targeted?

At the time of the protests, the Hefazat-e-Islami, a fundamentalist organization, started a counter-protest against the Shahbag Protests. It was really an excuse to attack minorities. They declared a war against all the bloggers and writers who were instrumental in starting the Shahbag Protests. They started riots on the streets of Bangladesh. When the government ordered a crackdown, the police fired on the Hefazat-e-Islami counter-protesters and nearly 150 extremists died. The government then decided to have a dialogue with them, and a pact was formed between the fundamentalists and the government. A list was issued of 84 writers and bloggers, who were made the scapegoats.

Although the authorities blamed these bloggers for writing against religion, I believe that the writers were expressing their views on fundamentalist perspectives within religion. Very soon, four of the bloggers were arrested for atheism. Hefazat-e-Islami had about 100,000 Qawmi madrasa students join in their counter-protest and siege the streets of Dhaka. They resorted to riots, and again the government cracked down—this time at night.

At that time, different organizations each had their own list and carried out their own vendetta against bloggers and writers. One of the organizations happened to be a list from Barisal which named three poets, including myself, as well as a sculptor, a socialist student leader, and a TV journalist. The common thread was that we were all activists in the Shahbag Protest.

I wanted to highlight the soft nuances, the emotions, the very feelings that we express. It is those beautiful feelings—the ethos, pathos, that we all have in us—that were being slowly lost.

After the lists were released, writers and bloggers began to be killed. What was it like for you to witness the threats unfolding?

I had received threats before. In 2006, I had written an open letter in a daily newspaper, entitled Islamization of Culture in Bangladesh. Along with a few other authors and contributors, it did trigger a few threats against me. None of those early threats were worse than what I faced in 2013, when six people were killed.

In 2014, one of my very close friends, a lyricist and poet who had written songs that were sung in the Shahbag Protests and who was involved in many liberal movements, went missing from Dhaka. I was scared. But in 2014, there was only one person from the initial hit list was murdered, so I thought that maybe it would die down. But in February of 2015, Avijit Roy was murdered. I became more cautious, more observant of the situation.

By August of 2015, four more people had been killed. A couple of the murders were in the middle of the night, but others were in broad daylight in a public place. I did not venture out much, and tried to do all my writing and editing work from home.

Three days before my name appeared on the list, Niloy Chatterjee, who wrote under the name Niloy Neel, was killed inside his own apartment. His two friends were tied up outside, while the others went inside and hacked him to death. I never would have believed that these people would have the guts to actually come inside. Now I was terrified.

I went to the police. They said, “Maybe you should go to India. They will accept you there since you are a Hindu.” Then they asked for all of my writing, and they started taking photocopies of my works. I felt more cautious, that something was not right. I decided to go underground.

Before Niloy Chatterjee was killed, he wrote on Facebook, “I am being followed. When I went to the police, they did not take my complaint, and they denied this fact.” The police also told Niloy to leave the country if he wanted to be safe.

Graphic by Nathan Deron.

How did the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act impact the police’s handling of your case?

Under Section 57 of the ICT Act, writers can be imprisoned if we hurt somebody’s feelings. The exact offense is not explained but as a result of the Act, writers left and right are facing charges.

When I went to the police, they took print-outs of all of my writing and told me that if I continued they would imprison me. They have a file where they keep everyone’s blogs. They also took my Facebook IP and password, even though I felt my privacy was being encroached upon.

When it was clear that the police could not help you, you went into hiding. How did you manage to survive during this time?

I was followed home, and that triggered me to escape into hiding. I was extremely traumatized.

At first, I went to my closest relatives in the villages, and they were very scared. They said, “We don’t want to be affected by this.” The story was being broadcasted on the television, so they feared they might have bear the brunt of the whole thing. I only spent one night with them, and then I went to Chittagong, the second largest city in Bangladesh. I started living with my friend.

Then some people got my number through the mobile banking system, which my father was using to try and send me money. When I began to receive calls from unknown numbers asking where I was, and started being followed, I left Chittagong. I kept changing my address throughout four different districts. On October 31, I received news that two different groups attacked two publication houses at the same time. One publisher was killed, and three other people were injured. When they were attacked, the publishers’ pictures and their views were broadcast in the media. Some old video footage of me speaking for the cameras on behalf of myself and other writers, saying “our lives are in danger,” was included in the broadcast. Anyone could identify me. I could not go out, not even for food.

Some fellow writers, friends who helped me with money, and some who provided shelter, helped me get along.

I applied to the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN) the September I was in hiding. In December, I received a message from Pittsburgh saying I could apply for a visa. Some close, trustworthy friends accompanied me to the consulate. Before I left, I could only see my father and one other friend.

In April you arrived at the City of Asylum in Pittsburgh. What was your initial impression of the city?

Bangladesh is a country of rivers. Barisal, where I was born, is famous for its paddy fields and canals. It’s called the Venice of Bengal because of all the rivers that crisscross the region.

When I came here, I saw the rivers, the bridges, and the murals on the houses around me really touched my heart. This is a very appealing city for a person who loves art. I feel that I am at home. I miss the fish of course, but I like it, and the warmth of all of the people here touches me.

What are you writing now?

I am working on editing a manuscript of short stories I brought with me. It will be my first short story collection.

In my last days in hiding, just before leaving Bangladesh, I started working on a novel about persecution. I am still working on it, because I find that there are many emotions I cannot express through my essays—subtle feelings—that might reach more people if I can channel them through a novel.

Has your perspective of Bangladesh changed now that you’re in Pittsburgh?

I think about how Bangladesh compares to other countries in the world. Look at Afghanistan. In the ‘60s, Afghanistan was a very progressive country. And then look at Iraq. Look at Syria. There was a time where people were more modern in thinking, they were more open, and the societies were more open too. Then slowly the more fundamentalist groups took over, and they started suppressing and oppressing freethinking people in the name of religion.

Right now, Bangladesh has these small pockets of fundamentalism. But if it is not controlled now, if we do not protest now, these small groups are slowly gaining majority, slowly gaining in numbers, and they will slowly take over. And when they take over, they don’t just take over the system, they take over people’s minds; they control everything.

What is happening right now is a warning signal. Maybe something larger is coming up if we are not aware, and if we do not protest.

There is a lot of counsel needed in Bangladesh, and it cannot be done just within the country. Pressure can come from the outside as well, to influence the government to encourage free thinking, encourage more education in all fields of life, and encourage the communities to not be controlled by religion itself and to think outside the box.

A lot of counseling is needed: about religion, freethinking, and sex. If I ever get the chance to counsel on these aspects, I will do it freely to bring up Bangladesh.

What are Bangladesh’s best hopes?

I am very optimistic. Bengalis have been suppressed before and faced oppositions before, but we have been able to rise like a phoenix from the ashes.

At one time we were forced to speak in Urdu. We won back the right to speak Bengali, our own language. In 1971, we had won our freedom from Pakistan and we became Bangladesh. In 1992, we formed the people’s court, where we could all could pass judgment on the war criminals who had killed millions of men, women and children in the 1971 war. In 2013, members of multiple generations joined together to demand justice be served to these war criminals. Bengalis have experienced revival and protest, and one day we will all rise again. These communal powers will be defeated and maybe one day I can go home.

2 Comments on "The Bonsai Poet of Bangladesh"

Welcome, Tuhin Das. I’m glad you are safe, and I hope one day to meet you in Ithaca.

Edward

(a fellow writer, ICOA, Ithaca, NY)

Trackbacks for this post