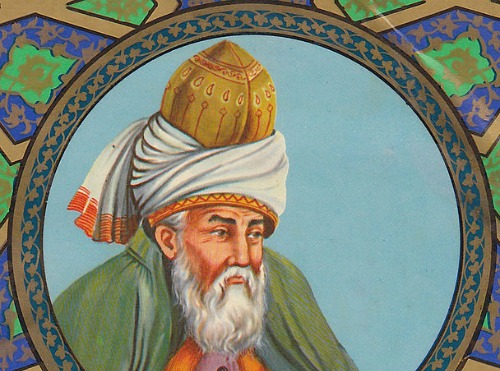

Rumi For The People

As the West makes the Master more accessible, his work and message are debased.

At the end of Farrukh Dhondy’s Rumi: A New Translation, there is an essay called “Rumi, Sufism and the Modern World” in which the British writer explains the relevance of Sufism to today’s world. As the “mystical, philosophical and aspirational” essence of Islam, Sufism, Dhondy believes, has “a vital role to play in our times.” He recognizes Rumi as the voice of this movement, and sees the thirteenth-century poet’s call for love and tolerance as a direct contrast to the more violent, politically motivated movements that have tried to dominate the world’s discourse on Islam.

- Pakistan is a country of contradictions – full of promise for growth, modernity and progress, yet shrouded by political, social and cultural issues that undermine its quest for identity and integrity. My bi-monthly column “Pakistan Unveiled” presents stories that showcase the Pakistani struggle for freedom of expression, an end to censorship, and a more open and balanced society.

- Bina Shah is a Karachi-based journalist and fiction writer and has taught writing at the university level. She is the author of four novels and two collections of short stories. She is a columnist for two major English-language newspapers in Pakistan, The Dawn and The Express Tribune, and she has contributed to international newspapers including The Independent, The Guardian, and The International Herald Tribune. She is an alumnus of the International Writers Workshop (IWP 2011).

I’ve seen this argument taken to undesirable extremes, by various scholars and so-called experts on Islam or South Asia, who have called for Sufism to be “used” in the War on Terror as a counter to jihadist ideology. In my opinion, this is a terrible appropriation of a deeply personal expression of faith and worship. And yet even before the War on Terror, Sufism had experienced cultural appropriation by those who wanted to divorce it from its Islamic context and adopt it in the style of “hippy freakishness” that Dhondy so wittily excoriates in his essay.

I also couldn’t help giggling as I read of Dhondy’s blistering disapproval of “prosaic tidbits to flatter the fans of pop divas who want to turn their attention to acclaimed poetry.” Several years ago I’d purchased a Buddha Bar CD and cringed as I listened to Deepak Chopra reciting lines from Rumi’s Masnawi in an oily voice while Madonna moaned and groaned in accompaniment and a house beat throbbed in the background, evoking the atmosphere of a Manhattan dance club.

The verses of the Master were never meant to be a backdrop to the orgasmic debauchery of the hip and the beautiful, but this is what he has been reduced to for those who are exposed to him without context or knowledge.

Later, in Dhondy’s second essay, “A Personal Note,” he turns his analytical eye to some of the modern translations of Rumi, and explains how the very people who attempt to bring Rumi to a wider audience have done him a vast disservice by misinterpreting the basic tenets of his message. Dhondy accuses Coleman Barks in particular of turning Rumi’s verses into the “random evocation and illogical juxtaposition of images” that make no sense and evoke no sensory or poetic response.

My own experience of reading Coleman Barks’ translations of Rumi has been similarly frustrating, if for different reasons. I began to read The Big Red Book, a huge collection of poetry in honor of Rumi’s companion Shams Tabrizi, organized into sections by Barks with titles of his own choosing, not Rumi’s. I gasped when I saw that Barks had used some of the 99 names of God—names such as Al-Fattah (the Opener) or Al-Rahim (the Compassionate); he expounded on these names with no reference to their being qualities of Allah, as Muslims firmly believe, but instead offered his own ideas and illusions about their significance. Never mind the whirling dervishes: Rumi would have whirled in his grave!

Which brings me back to my original concern about the cultural appropriation of Rumi. In making him available and accessible to modern times and interpretation, what if what we’ve perpetrated is the kidnapping of Rumi from the Islamic moorings in which Sufism originates, and held him hostage to our own whims? Such whims that only satisfy the ego, not the soul, because in buying a CD or wearing a T-shirt we think we’re accessing some deep mystical truth, when what we’re doing is commodifying that which cannot be commodified. Rumi was all about freedom from illusion, but I feel we’re no closer to the truth: In trying to bring Rumi to the people in a popular way, we’re trying to bottle sunlight, and sell it for a song.

One Comment on "Rumi For The People"

Thank you. Looking forward to our collaboration in Konya.