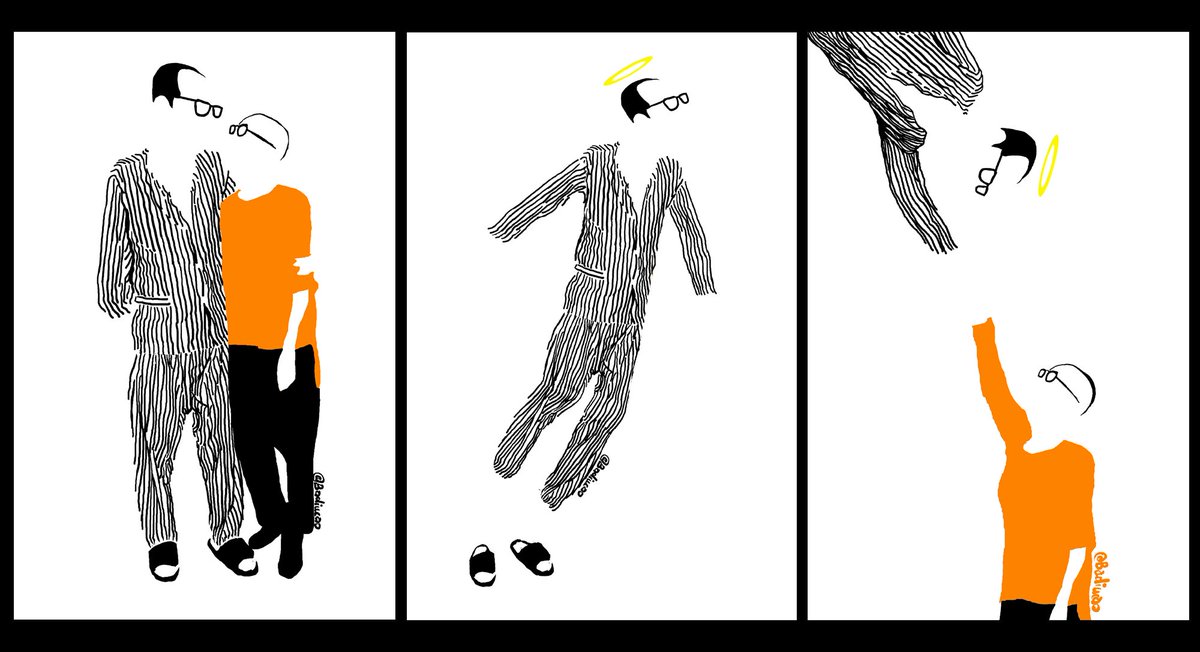

The Beautiful Love Story of Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / October 17, 2017 / No comments

Image via BBC.com

The beautiful love story of Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia

Liu Xiaobo and his wife, Liu Xia, have written many poems dedicated to each other. Most of the poems were composed when they were apart, that is to say, when he was in jail, and she was alone at home under house arrest. She married him while he was in re-education camp in 1996. For both, it was their second marriage. She left her first poet husband and was attracted to Xiaobo when he was agitating at the Tiananmen Square during the protest movement in 1989. At that time, after he had divorced with his wife, Tao Li, and had left his son, he had many admirers and lovers. Liu Xia was one of them. In her poem dedicated to Xiaobo, with the title “1989 June 2” (June, 1998), she wrote:

…

Standing behind you

I pat you head

The hairs stitch into my palm

What a strange sensation

I don’t even have time to say a word to you

You are a media darling

Midst in the crowd I look up to you

It makes me feel tired

Withdraw and hide myself outside

I smoke

Watch the sky…

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison til 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners, and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

Their love intensified in the following years. He felt guilty, dragging her into trouble because of his political activities. During his three-year incarceration (1996-1999), he wrote many passionate poems to her. She responded to him with more subtle lines. At that time, Xiaobo was a prominent prisoner, and he received special treatment, so that he called himself sarcastically an “aristocrat in prison”. In his letter of January 13, 2000 to Liao Yiwu, he wrote:

“Compared with your years in prison, my three prison stints were pretty mild. During the first, at Qincheng, I had my own cell, and my living conditions were better than what you had to endure. Sometimes I was deathly bored, but that’s about it. In my second stint – eight months inside a large courtyard at the base of the Fragrant Hills outside Beijing – I got even better treatment. There, except for my freedom. I had just about everything. During the third three years at the reeducation-through-labor camp at Dalian, I was again singled out for special handling. My three elite-prisoner experiences can’t compare in any way to your suffering; I probably shouldn’t even say mine were imprisonments, compare to yours.”1

The “nobleman” treatment in jail had enhanced Xiaobo’s self-confidence, so that he felt “free” to talk about death. In his poem “What one can bear”, which he dedicated as “for my suffering wife”, one finds that the sentences in it sound almost as playful as between two young lovers when they suffer under separation. It was composed in Dec. 28.1996. Today, when we read it, it is so painful and ironical:

You said to me

“I can bear anything”

with stubborn eyes you faced the sun

until blindness became a ball of flame

and the flame turned the sea to salt

Beloved

Let me ask you through the dark

Before you go to your grave, remember

To write me a letter with your ashes, remember

To leave me your address in the netherworld…2

What Liu Xiaobo did not reckon in the first three years of imprisonment, is that the government wanted his death after he received the Nobel Prize, when he was in prison for the fourth time. So many Nobel Peace Prize laureates become statesmen later, such as Lech Walesa, N. Mandela, and Aung San Suu Kyi. The Beijing dictators did not want to take any risk that Liu Xiaobo would follow their steps and became the president in China one day. They let him become terminally ill in jail and kicked him out to die in a hospital. There were only 5 weeks between his parole for medical treatment and his death on July 13. The Chinese authority cremated his body and scattered it into sea. He has no grave in his beloved home country; people could not gather at his grave to mourn. He could not write any letter with his ashes to his wife. What he did was only to whisper to her ears before he stopped to breath: “go, go out, leave this country.”3 The inhumanity and cruelty of a dictatorship is beyond the victim’s imagination.

Through a private channel, we saw the poem which Liu Xia wrote to Xiaobo in 2010, the year he became the Nobel Peace Prize laureate. We do not know whether he had ever had the chance to read it before he died.

Road to Darkness4

Sooner or later you will leave

me, one day

and take the road to darkness

alone.

I pray for the moment to reappear

so I can see it better,

as if from memory.

I wish that I, astonished, could glow, my body

in full bloom of light for you.

But I couldn’t have made it

except clenching my fists, no letting

the strength,

not even a little bit of it, slip

through my fingers.

As if she already knew seven years ago, what would happen in summer 2017, that she would lose him. She could not make her body glow to light him in darkness, because she was captured by the state forces. During the whole process of Xiaobo’s death, the couple could not have any privacy to speak any intimate words to each other without being heard by the big brothers. Since his death, she herself has been in total darkness too. She is again under house arrest, maybe kept in a hospital, so that no one can find her. With Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia, the totalitarian regime has created a huge tragedy. Meanwhile, the couple Liu has written down the most beautiful love story of our time.

1Translated by Perry Link, from Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred, Selected Essays and Poems, p. 286, 2012 Belknap Harvard. 2Translated by Isaac P. Hsieh, from Liu Xiaobo, No Enemies, No Hatred, Selected Essays and Poems, P. 58, 2012 Belknap Harvard. 3Sourceed from a private mail Liu Xia sent to a friend in August. 4Translated from the Chinese by Ming Di. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/09/28/road-to-darkness/