Mirror Images

by Vijay Nair / October 29, 2012 / No comments

A column by City of Asylum/Pittsburgh’s guest writer Vijay Nair

The Times of India from February 22, 2006 after the trial of Jessica Lal's killer. It is just one of the many cases of India and Pakistan's media coverage examined below by Nair.

The 1947 partition of British India into the two sovereign nations of India and Pakistan displayed unprecedented violence on both sides of the border that divided the countries. Decades later, the wounds continue to fester and any tragedy that befalls one country becomes the subject of intense media speculation in the other. In the last month, the Indian media hasn’t tired of writing and commenting on two ‘breaking news’ items that have provided fodder for the leading news channels and newspapers.

The first had to do with the rather flippant and unsubstantiated rumors about the foreign minister of Pakistan having a tumultuous romance with the young scion of the first family of the country. The meat of that story lay in its salaciousness and no doubt dominated the conversation in many high profile parties in New Delhi.

The second one is more serious. It has to do with a story that pierces the gut almost as savagely as the bullet fired by a Taliban assassin, which grazed the skull of fifteen year-old school girl Malala Yousufzai. Malala, at a surprisingly tender age, had taken to championing the cause of women’s education and empowerment through her writing. This, at a time in her life when her peers must have been preoccupied with their first crushes and the messy business of falling in love. There is something very moving in the tale of this brave champion. Not just Indians, but the entire world has been praying for her recovery as she recuperates in a hospital in the UK.

For most Indians—and I include myself in that count—our own sovereign democratic republic happens to be a ‘freer’ land with democratic processes and guaranteed freedom of speech. There was a brief spell of darkness when one of our Prime Ministers imposed a state of emergency in the mid-1970s for a year and a half and many of our writers and thinkers found themselves behind bars. But barring that aberration, we believe that we are a more privileged lot than our Pakistani counterparts; it is not just in the game of cricket that we hold the upper hand.

The truth is, like everything else in a country that thrives on contradictions and complexities, there are shades to this reality. Although the constitution guarantees Indians the right to free expression and speech, successive political regimes, irrespective of party affiliations, have been a lot less tolerant when it comes to citizens exercising this particular right than any other.

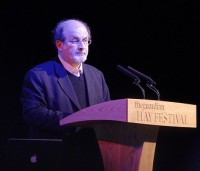

Author of The Satanic Verses and advocate for freedom of speech issues Salman Rushdie. Photo: Alexander Baxevanis

Earlier this year, Salman Rushdie found himself gently eased off the guest list at the Jaipur Literature Festival, the biggest literary event organized in the country every year. The organizers wanted him but the political establishment did not. Elections were around the corner in a few states and a fringe Islamic extremist group, raking up the old Satanic Verses issue, had expressed its displeasure about having him in the country. That was enough to force the organizers of the festival to communicate to Rushdie that maybe it would be better if he didn’t appear for the discussion he was meant to chair.

This of course led to outrage in a certain section of society and the political establishment came under heavy fire from the media. But they say politics makes strange bedfellows. The Indian political establishment’s stand was endorsed by the suave playboy cricketer turned politician of Pakistan, Imran Khan. Khan, who was meant to be a part of the same panel as Rushdie, refused to share the dais with him.

Rushdie had to back out eventually because of security reasons. He did appear for another televised event in India a couple of months later. But by then the elections were over and no one was worried that he may pose a threat to their bank of voters. With his characteristic wit and flair Rushdie took on both the Indian establishment as well as Khan, providing robust entertainment for the viewers as long as the show was on air.

A few months prior to the Jaipur festival fiasco, another well-regarded Indian literary figure faced the fire. Arundhati Roy, the much feted writer of God of Small Things, attended a seminar that also featured a few political leaders from Kashmir who are suspected extremists. Roy was not endorsing the political stance of these leaders. She was merely a part of the same panel, there to debate and discuss certain issues. This time it was the media that got on her case. The lead anchor of a television channel promoted by the largest media group in India went ballistic on air, accusing her of sedition, alternately hectoring her and encouraging the government to arrest her. Roy later confessed to being afraid of the man who claims to be the conscience of the nation on prime-time TV. It is amazing to note how many of the so-called liberal thinkers and writers in India are hostile towards Roy merely because she champions the cause of the dispossessed, some of whom have resorted to violent means of protest because the establishment persists in taking away their land and livelihood in the name of development.

There was also the recent case of the young Dalit poet, Meena Kandasamy. Kandasamy was one of the writers hosted by City of Asylum/Pittsburgh when she came to the US in 2009 as part of the University of Iowa’s International Writers Program. She was first noticed by Hindu fundamentalists when she ended a bad marriage plagued by domestic abuse and chose to publish her experiences in a leading Indian weekly. The piece won her as many ardent admirers as trenchant critics. As far as the Talibanesque right-wing Hindu fundamentalists are concerned, Kandasamy added to her ‘sins’ by attending a university-organized beef festival to protest against the ban on the slaughter of cows, which form the staple diet of Muslims and the lower caste Dalits. She was inundated with hate mail and tweets, some of which threatened to get her gang-raped in public for daring to attend such a festival.

There is also the almost farcical story of a professor in Calcutta who found himself behind bars on charges of “violating the modesty of a woman” for posting a few innocuous cartoons of the Chief Minister of West Bengal on Facebook. The chief minister happens to be a feisty firebrand leader of a political party that, like any other political party in India, has many recruits with proven criminal charges against them. There was nothing remotely sexual about the cartoons of her the unsuspecting professor had posted.

Obviously there is a price to be paid for the freedom of expression and sometimes what is demanded in lieu of it is life itself, as Safdar Hashmi must have realized in his dying moments. Hashmi was a writer and a filmmaker during the 1980s. His chosen way of protest was street theatre and he was in the middle of a roadside performance when some goons led by a member of the ruling party lynched him in broad daylight in the presence of a shrieking audience. In a poignant twist to the tale, his wife went to the same venue a couple of days after his death and completed the performance from where it had been interrupted. Hashmi was 35 years old when he was killed.

But the striking parallel to the Malala Yousufazi in the Indian context lies in another grim tale, although the protagonist of this particular story was totally apolitical and nursed no ambition to change the world. Jessica Lal, a not so successful model in New Delhi, was supplementing her income by working in an unlicensed bar owned by a socialite who threw celebrity parties. Her boss had asked her to stop serving drinks after midnight. One night, in walked the son of a powerful politician and demanded a drink for himself and three of his accompanying cronies. It was long past the closing hour and Jessica told him politely that the bar was closed. He whipped out a pistol and shot her in the head, killing her instantly.

Times of India headline from August 15th, 1947 covering the freedom movement in India. Photo: The Times of India

In the shady aftermath, everyone ranging from those present in the party, including the eye witnesses, to the police, to the criminal justice system, tried to cover up the crime. The trial that ensued saw the criminal walk off scott-free. It was left to Lal’s grieving sister to mobilize public opinion against what had happened. The media supported her cause and like a sign from heaven, in a country where life and Bollywood are strangely intertwined, a big anti-establishment blockbuster evoking memories of the freedom movement was released at the same time. The film Rang de Basanti further fueled the public’s rage. Candlelight vigils became the order of the day. Despite all kinds of political pressures, a retrial was ordered in a fast-track court and the murderer found himself behind bars. He is cooling his heels there despite all attempts by his political patrons to get him out on parole. The ever vigilant media and Lal’s friends and family, backed by public support, have ensured that there is no easy reprieve for him.

A critically acclaimed feature film on the episode has also been released recently. The title of the movie is telling: No One Killed Jessica.

One can only hope the Malala Yousufzai incident stokes a similar fire across the border, that her sacrifice does not go in vain, and is documented for posterity.

She deserves it.

Vijay Nair is a playwright and writer from Bangalore, India. His published works include a collection of plays, two novels, and a non fiction work on Indian organizations. At present he is a Fulbright Fellow on a senior research grant, being hosted by City of Asylum/ Pittsburgh.