Film Review: Neither Burma nor Myanmar

by Ko Ko Thett / December 29, 2011 / No comments

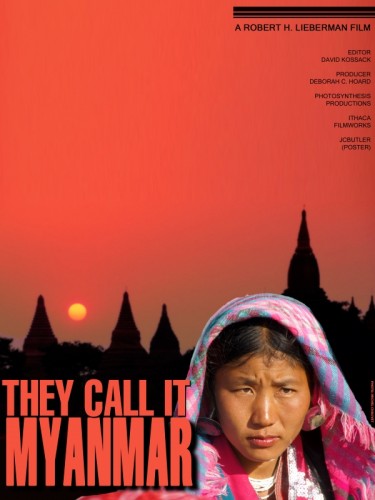

They Call it Myanmar: Lifting the Curtain was screened for the first time at the prestigious International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam on November 19 to a packed cinema. It premiered in Vienna earlier this month, and was similarly well-received.

The film was conceived a few years ago when American author and filmmaker Robert H. Lieberman was invited by the US state department to shoot a documentary about Burma and got involved in some art projects with locals in the process. Liberman says the target of his film is the people who know nothing about the country.

The most relevant of these people may be American voters concerned over Obama’s foreign policy shift towards what Hillary Clinton now refers to simply as ‘this country,’ neither Burma nor Myanmar. After all, a very challenging election awaits Obama next year. His popularity rating needs to be maintained if he is serious about getting re-elected.

The US détente with Burma has been in the making over the last decade. Clinton’s December visit was not a knee-jerk reaction to recent reforms in Burma. Rather it is the first in a series of carefully calculated rewards to Naypyidaw for living up to some of Washington’s expectations, most importantly President Thein Sein’s accommodationist policy of the West, the government’s deepening role in ASEAN—and consequently lessened affiliation with China—and its dialogue with dissident leader Aung San Suu Kyi. We now know that some more benchmarks were set during Clinton’s visit.

As Lieberman stresses that Burma has been the most isolated and quaint country in the world in the opening scene of the film, another state-sponsored American documentary about Burma that came out after John Foster Dulles’ visit of the country in 1955 sprang to mind.

The opening lines of the old film are remarkable, “Today there are many new small nations around the world of which we know very little…in 1949 our foreign aid experts were inclined to write Burma off. A small nation, about nine-tenths of it already in the hands of the communists, with only a very small army, it was led politically by what was regarded as a religious fanatic, a little man who spent most of his time meditating.” Little did the US policy makers know which direction newly independent Burma was taking.

Unlike his predecessor, Lieberman does not attempt to explain the suffering of the Burmese people, nor reproach its leaders by name. His take is hands-off and non-judgmental—Burma as he saw it through his lens when he was passing by. From the black gaping holes in the pavement to the red propaganda billboards, it is a raw presentation of impoverished Burmese lives who comprise up to ninety-five percent of the country’s estimated fifty-five million.

Lieberman constructs a series of interviews to highlight the dire situation of economy, education, health care, infrastructure, and culture in one of the poorest nations, ruled by some of its wealthiest people. The film presents an uncompromised look at the paradox of a land still struggling with its new image, trying to grapple with developments and distribution of wealth, and attempting to be integrated into global politics, while ostentatiously hanging on to its old institutions, history, and economic dynamics.

Unlike the untitled documentary of the 1950s, Lieberman did not seek, or was not granted, interviews with movers and shakers of the new Burmese government. For security reasons, nor was he able to identify his interviewees, many of whom are very articulate and passionate about their country.

Ruthless edition of over 120 hours of footage shot over the past two years into just over an hour gives the viewer a film of mesmerizing diegesis. They Call it Myanmar is the type of documentary that asks more questions about its subject than it answers.

Unfortunately, some of the most enduring myths about the country have been strengthened by the film. Take, for instance, the myth of Burma’s prosperity before the 1962 military coup, or under colonial rule. It is true that Burma was ‘a rice basket of Asia’ before independence. Rangoon even shipped rice to a US hit by the Great Depression, but rice exports in colonial Burma did not translate into well-being for the Burmese populace, especially the peasantry. Take another instance, the Burmese kings’ alleged sacrifice of virgins as cornerstones in the construction of their palaces. Historian Dr. Than Htun attempted to break such myths when he asked, “Why don’t you go and dig the corners of palace sites and see if there are bones?”

All in all, They Call it Myanmar is sobering even for a Burmese. Gripped by one of the most graphic portrayals of destitution and dukkha (a combination of misery, suffering, and angst) of the Burmese people, I did not realize I had already marked “excellent” on the commentary form towards the end of the documentary. Despite problems at home and the waning of Washington’s global influence, perhaps American soft power is getting even softer.

Ko Ko Thett is a poet, literary translator and political commentator from Burma. With James Byrne, he is the co-editor of Bones Will Crow, Fifteen Contemporary Burmese Poets. He lives in Vienna.