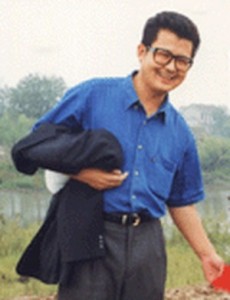

Chinese Writer Guo Feixiong Released from Prison

by Caitlyn Christensen / September 23, 2011 / No comments

Writer Guo Feixiong, a member of PEN Center, was released from Meizhou Prison in China’s Guangdong Province on September 13. He served a five year sentence. Rights groups and Guo’s wife say that he suffered abuse during his detention and imprisonment, but the activist and writer is reluctant to linger on the details of his “special treatment.”

Guo Feixiong, also known as Yang Maodong, is a Chinese dissident novelist and essayist, independent publisher, and rural civil rights advisor and activist. In 2006 he was charged with selling 20,000 books using false ISBNs, an illegal publishing practice.

According to his wife, Zhang Qing, the charge was unfounded. His lawyers said the arrest was connected to the publication of a book entitled Earthquake of Shenyang Government, which Guo edited but did not write. The book exposed government corruption in China’s Liaoning Province. Despite the government’s claims that he was arrested for business violations, he was only asked about his political activities while in prison.

Guo faced years of government harassment prior to his 2006 arrest. In 2005, as a legal advisor at the Beijing-based Shengzi Law Office, he was detained for more than three months after attempting to help remove a corrupt director from the village of Taishi‘s local committee. Since that detention Guo was repeatedly harassed by authorities. In August 2006, two months before his imprisonment, he was beaten by railway police for allegedly carrying a false ticket on the train. Guo is a member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) and wrote for news websites about Taishi’s perilous political situation, activities which may have contributed to his persecution and arrest.

Zhang Qing, who was granted political asylum in 2009, and now lives in the United States, wrote about Feixiong’s prison experience in a letter to Human Rights in China (HRIC):

“On December 28 [2007] we saw Guo Feixiong at Meizhou Prison for the first time. Through the glass partition, I could see that his body was stiff, and he wobbled as he walked to the visitation area. He was pale and his lips were lifeless; he was emaciated.

He told us that on his first day at Meizhou Prison—December 13, 2007—the prison [guards] threatened him, and forced him to do physical labor… He was not permitted contact with other prisoners, or to read the newspaper or any books from the library. He was not allowed to cross the three yellow security lines painted on the ground in front of his door. They also threatened to send him to a mental hospital.

He began his hunger strike on that day and planned to continue it for 100 days. He was doing this to call upon the Chinese government to improve the prison conditions for political prisoners, prisoners of conscience, and those persecuted for their religious beliefs, and to initiate political reform.

On the fifth day, [the prison guards] secretly arranged for a prisoner to beat him. During the long course of the beating, he tried four times to speak, but prison guards covered his mouth and deliberately injured his chin. The beating occurred in front of 200 prisoners, who were unable to do anything. It wasn’t until [the prisoners] all raised their voices that the beating finally stopped.”

Guo’s hunger strike failed when he became dangerously sick. He confessed to his charges while undergoing torture.

Guo’s poem about the Guangdong Province elections, “Worry Free Songs” was published in the online “Collection of Human Rights Poems,” an anthology of China’s censored history in the new century. Guo was an honorary chief editor of the anthology, which the Chinese government banned in 2008. “Worry Free Songs” has not been properly translated by an authenticated source, but in a rough translation the poem speaks of dreams of political and religious ancestors—“Confucius, Mencius, the Bible, which sustains.”

Although Guo’s treatment in prison has left him physically weakened, he strives towards reconciliation. “I don’t care who did what to me in the past,” he told HRIC. “…I am filled with optimism for the future.”

He also said to the Associated Press: “The only thing I can tell you [about imprisonment] is that I was given special treatment beyond people’s imagination in the detention center and in prison. I don’t want to talk about it in detail. I want to convey a message of forgiveness to the public and not to talk about hatred.”

Guo maintains his political views have not been swayed. “No amount of ‘special treatment’ [in prison] would make me more radical or weaken me. My conviction in defending the rights of people has not changed in the slightest.”