Do Wars Justify Censorship? A Dilemma Not Easily Answered

by Margot Tudor / September 16, 2014 / No comments

via Flickr user: IsaacMao

This article is part of Draw the Line. Each month, Index’s youth advisory board will choose a free expression topic and encourage readers to respond to the issues it raises. Youth board member Margot Tudor wraps up the last month’s discussion.

This month’s Draw The Line debate has shown itself to be a dilemma not easily answered in four weeks. Many of the responses we received have acknowledged that it is hardly a black and white topic but with conflicts flaring up all over the world it is an incredible important question to consider. As Usamah Mohamad writes on Twitter, “I think it is justified on a case by case” and therefore will not be answerable in umbrella terms. But can some countries prevent the media from full access based on it being a risk to security? Can conflict be a genuine excuse for censorship and the restriction of free expression?

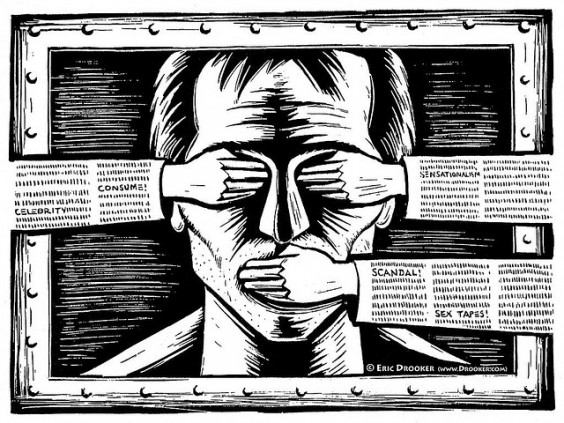

An article written by Pat O’Mahony pitches in on the argument that the mainstream media has often its own agenda in maintaining “taste and decency”. He uses the example of Kenneth Jarecke’s renowned and “harrowing” picture which is an image which truly shows the reality of the Gulf War. Interestingly, he delved into the idea of self-censorship which involves us changing the channel, scrolling away or turning off the information entirely because even if the mainstream media does show the clips, it might be too much for us. O’Mahony describes this as a “remote control moment”. His analysis is well worth a read and he leaves us with a further unanswerable question: “In this social media era [where distressing images are a click away] should television news and newspaper editors still try to protect us from its full horrors?”

Even if we do not want to consume the media, however, shouldn’t journalists have the freedom to watch without prosecution? Such as with the criminalisation of the video of James Foley’s beheading there have been outcries of the Met police censoring journalists. An article by Index’s own Jodie Ginsberg has examined the “deeply problematic” removal of such media, especially when journalists themselves are banned from viewing the material. She argues that the Metropolitan Police cannot expect journalists to be able to report fully on an item without viewing it themselves. It’s a disturbing part of the job but it is vitally important.

Many have argued on Twitter that imposing censorship in times of war – particularly with the restriction of the internet (as seen in Ferguson and Turkey) and media access – will allow the government to continue censoring in the public interest even once the conflict has ended. As with the use of martial law to keep the peace throughout history it is often a tool of the state to restrict civilians from protesting about their treatment. Even in times of war there must be space for the provision of human rights and freedom to protest. Sheema Ghani offered the point that clamping down on critical civilians and journalists by using war as an excuse for censorship is just as good of a solution as sticking your head in the sand.

Overall, there is an understanding that some information – particularly in tenuous situations – must be kept private from citizens for the sake of state security. But with the introduction of social media and the ability for civilians to become journalists with Twitter accounts, the truth is trickling out of these conflicts despite the best efforts of their initiators. Violations are no longer kept secret as long as the Wifi connection holds up and this is a great leap forward for free expression.

The IFEX network of organizations is connected by a shared commitment to defend and promote freedom of expression as a fundamental human right. Check out IFEX’s website or follow it on Twitter, Facebook or YouTube.