Why We Write: Inside the Creative Process with the Poet Laureates for Allegheny County

by Renee Cantor / May 20, 2021 / Comments Off on Why We Write: Inside the Creative Process with the Poet Laureates for Allegheny County

Pittsburgh is a city of poetry. Maybe it’s something in the air. It inspires poetry and grows poets. At Sampsonia Way, we support the City of Asylum’s belief that “All Pittsburghers Are Poets.” In coordination with City of Asylum, we published one poem a week written by residents of Allegheny County from all walks of life over the course of the past year. Through these poems, we have celebrated different cultures, mourned losses, explored religions, appreciated nature, and more.

Pittsburgh is a city of poetry. Maybe it’s something in the air. It inspires poetry and grows poets. At Sampsonia Way, we support the City of Asylum’s belief that “All Pittsburghers Are Poets.” In coordination with City of Asylum, we published one poem a week written by residents of Allegheny County from all walks of life over the course of the past year. Through these poems, we have celebrated different cultures, mourned losses, explored religions, appreciated nature, and more.

And while we believe that all Pittsburghers are poets, we recognize that everyone has their own process of getting there: their own poet origin story. To conclude a year of poetry, we’ve explored the broad philosophical questions of how someone becomes a poet and what it means to sojourn through the creative process. In other words, “Why write?” We posed these questions to Allegheny county’s four poet laureates; Vincent Folkes, Youth Poet Laureate; Paloma Sierra, Emerging Poet Laureate; Mj Shahen, American Sign Language Poet Laureate; and Celeste Gainey, City of Asylum Poet Laureate. Their answers have not only inspired my own writing, they have shed clarity on my understanding of myself as a writer. We hope they inspire you similarly.

Do you remember the first piece you crafted that you were excited about?

Vincent Folkes: It was probably a song to be honest. When I was younger — I don’t know how I did it — but I would listen to songs and kind of just block out the artist talking, and write my own thing to their song using their flow. And I think it was like Chris Brown’s “Deuces.”

Paloma Sierra: I first came into writing when I was eight years old. In school, we started doing poetry. And I think what first interested me the most about poetry was that it was kind of like a puzzle. I found it very fun, this idea of thinking of writing as a puzzle and finding the right word. One of the first poems I wrote was about my brother. For the longest time, my sister and I wanted a brother. And I guess I was very excited about the fact that I was going to get a brother so I wrote my first poem about him. When I say first poem, it was probably four lines long.

Mj Shahen: It would probably be an ABC story. In Deaf culture, ABC stories take all of the components of the letters of the alphabet, the handshapes, and they create a story. So knocking on a door with an ‘A’ handshape, okay? So the door opens using a ‘B’ handshape, slowly by itself. Someone’s grasping the doorknob with a ‘C’ handshape, holding my hand on the doorknob slowly and opening wide. It follows the handshapes of each of the letters to create a story. And I just became enthralled with those. And I saw that they were a part of our rich culture and our rich history.

Celeste Gainey: I had done lighting for… well, for close to 35 years [for the stage and for the hospitality industry]. And I kind of woke up one morning — I know that sounds crazy — but I just felt done. Not in a bad way. I really enjoyed what I did, but I just felt like I didn’t need to do it anymore. And so I started to write out of a kind of personal inquiry. What I was writing, I recognized as poetry. I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, but I did know that I derived so much satisfaction from doing it. But, I need to be in a context to be made to write. Like, I need deadlines, I need all of this sort of stuff. So that ultimately led me to looking at MFA programs. And I happened to choose Carlow.

When did you realize that you had something to say?

Vincent Folkes: Probably in high school. I was born in Jamaica and some of the issues that are relevant for a Black person in America are not necessarily the same for a Black person in Jamaica. It wasn’t that crazy of a thing to be black in Jamaica. But moving to America you see, you know, little things. Weird looks and stuff. Then in high school, I started learning things and then getting exposed to young black people dying, older black people dying, men and women dying all over the place. And it kind of just sparked rage and just a lot of confusing emotions. Through that I connected with other people who felt the same way. And I use writing as an outlet just to let that frustration out.

Paloma Sierra: Growing up, I always thought that poetry could be used to beautify things. It wasn’t until I got to college and started to think of writing differently that I started to also learn that you can use poetry to point out things rather than just beautify them — in the sense of sometimes not everything is beautiful. Some things kind of suck. And it’s okay to use writing to highlight those things as well.

One of the first times I noticed how I could use poetry differently was the summer after my freshman year of college. I stayed here in Pittsburgh, and did creative research in which I got to interview a lot of Puerto Ricans living on the island and those in diaspora. I tried to explore the different perspectives that people have about what it is to be Puerto Rican. And I guess doing that project was the first time I realized I could use poetry to show or talk about topics that I think are important rather than just talking about ordinary things and trying to heighten them.

Mj Shahen: Well, I go back to that eight year old little Mj, and how I looked at the people in the Deaf club and the way that I saw them construct language. I think that spoke to some inner part of me. And then I knew that at some point, I have those same skills. So in the beginning, with learning about poetry and reading poetry, it really didn’t strike me. And music, you know, didn’t resonate with me. A lot of Deaf people like music but that didn’t work for me. But there was something internally, and the more I studied the rules and the more that I saw other aspects of Deaf poetry, it just started to build inside me.

Celeste Gainey: It was just strange, because I think in the very beginning I was writing more into myself as a reference of inquiry. In other words, it was more metaphysical. It was more of an exploration of my spiritual self, in a way. And then when I got to Carlow, my teacher Jan Beatty said to me, “Listen, you’ve had this life, you’ve got more than most people have to write about.” In the beginning, I was a little shy to tap into that because it felt almost — in having been raised a good Catholic schoolgirl — self-aggrandizing in a way. So I really kind of stumbled upon what I fell in love with as a writer. I kind of rediscovered the writer that I always was.

When did you first consider yourself to be a creative or a poet? How did you figure that out?

Vincent Folkes: Probably after winning competitions for poetry. I think after I became a poet laureate is when I fully claimed the title “poet.” But it was almost like an identity crisis, because I’m doing all these things for poetry, but I’m also making music on the side. That’s my favorite thing. So I try to include all my titles, because I’m not just a poet, I’m not just an artist, or an entrepreneur

Paloma Sierra: I think the first time that I started to think of myself as a writer was presenting my first play in front of an audience. Of course, I don’t think I would show that first play to anyone anymore. But this idea of showing people your work I think makes anyone a writer. Yeah, you could write for yourself. But if no one other than yourself is getting access to the writing, are you a writer? I don’t know… So far, I’m calling myself a poet playwright. I also consider myself a translator. But I’m trying to redefine myself more as a writer because I’m not only writing in one specific genre, but a lot of different genres, including, film, theater and poetry.

Mj Shahen: I have art inside me. And I think we all do, to some extent. It’s expressed differently. … Probably graduate school. The reason for that is there was so much intense studying in graduate school. I studied oppression in the Deaf community and in other communities. And I really saw what happens to people when they don’t have a first language, when they are deprived of the language. I think that was the realization for me that I could speak to that issue.

Celeste Gainey: I think knowing myself as a writer or poet inside of myself came before my willingness to identify publicly as a writer or a poet. I think for many different little reasons, I was shy about identifying myself as a poet. I needed to have certain publishing credentials to really call myself a poet or a writer in a bonafide way. It was definitely after my MFA that I began to identify myself as one. Now, I don’t have any problem saying it at all. Definitely after I wrote my book, I felt really okay saying, “I’m a poet, and here’s my book.”

Have you ever struggled with impostor syndrome?

Vincent Folkes: Oh, yeah. If I would’ve let that get to my head, we wouldn’t be talking right now. I wouldn’t have entered [the poet laureate] contest because of feeling like my work wasn’t good enough or advanced enough. But I think what really helped me get over that is friends who really believe in my work and people who feel it, you know? People who feel the emotion of my writing. That tells me that what I feel is valid and it’s real.

Paloma Sierra: Oh, for sure. I have felt it a lot, mostly in my undergrad career and even as part of my master’s. But what has been important for me to get over it a little bit was to acknowledge what successes I’ve accomplished. And also acknowledging that what we really need to do is find our own supporting communities. It’s about finding that community with whom you share these interests and passions, connecting with them, and maybe even creating with them. And finding those communities, who are those people for me, has helped me get over those doubts over time.

Mj Shahen: Sometimes in the Deaf community, others look at how I do things slowly, because I really want the hearing community to understand. And deaf people are like, “oh, this is our language, and if the hearing community doesn’t understand, too bad for them.” I feel the opposite. So in terms of being a member of the Deaf community but also trying to expose hearing people to the culture and to the oppression we’ve experienced, the concept of imposter is more important.

Celeste Gainey: On the first day of Jan’s workshop, I introduced myself as the imposter because I felt like I was on some kind of a reality show. The kind of thing where they say, “Okay, well, we’re gonna take this ballerina, and we’re gonna make her a rodeo star in two weeks.” I was really starting from ground zero. So it was just lucky that I knew there was something that was anchored inside of me, where I just knew that this was something I had to do and that this was something I was meant to do.

Have you ever wanted to quit?

Vincent Folkes: I think for a year in high school, I stopped writing on purpose. I was going through high school love, and I was like, “Nah, I’m not writing about you.” My way of taking my power back was by not writing about them.

Recently, I went through a stage of just not having any inspiration, like I can’t write. But I saw this video by somebody talking about inspiration, and do you wait for inspiration to come? Or do you just get up and do what you have to do to get that goal completed? And I was like, you know what? He’s right. I’m not gonna keep listening to music, hoping that some song is gonna inspire a spark. And then that same day, I ended up writing half of a song. And that was super liberating, because I hadn’t written in like three months… I can’t give up because I know that there are people that I look up to who do what I want to do. And if they can get there, I can get there too, and maybe even higher than that. So it’s that hope for the future. And that passion too.

Paloma Sierra: Yeah, every once in a while I have a project, and I’m like, “Oh, my God, I hate this.” Oh, and I probably want to burn it. And I’ve thought about quitting. But then I disconnect a little bit from the project. And I’m like, “Do I really want to quit? Or is it that I just find this project hard?” And most of the time, it’s just that I find a project hard. And it’s fine having those feelings because I feel if I didn’t have them, I probably don’t care for what I’m doing.

Mj Shahen: Sure, I mean, burnout is definitely a thing that could happen. And I don’t feel compelled to publish on YouTube every day or Facebook. I don’t feel that pressure on me. And if I did, I probably would burn out. But for me, letting the hearing community know what I’m doing and having them ask me about my work sort of livens me up. And I love when they asked me to do poetry that they’re going to show somewhere

Celeste Gainey: I can’t imagine quitting writing. I can imagine it taking me places where it might expand. But I can see myself moving, at some time, into a more visual interpretation of things. I don’t know what that might look like at this point, but writing will always be a part of it, whatever it is. I think I’m too fascinated by writing to ever quit.

So, ultimately, at the end of the day why do you create your work? Why do you keep going even when it’s really hard?

Vincent Folkes: I write because it feels good. That feeling is, in the moment, that high-energy adrenaline when I write a super dope line, one after the other. Since I was young, that’s how it made me feel, through all my insecurities. But that’s how I would feel, just super geeked about making something that I was proud of.

Paloma Sierra: Writing in the pandemic has been hard for me, especially as I see the industry that I wanted to work in — theater — suffering right now. So what has been helpful to me to keep motivated has been collaborating with other people. For example, right now I’m working on my thesis, and I struggle to write that play, which is also in verse, because I’ll be thinking of the industry and not feeling like there’s a future right now. But then as I get the opportunity to work with my team — the actors and the director — hearing how they find the story that I’m telling important, it keeps me motivated to keep working and improving it. So sometimes it’s nice to distance yourself from the work a little bit. Or from yourself as a writer. And think about why you are telling this story. Why is it important? And why should others care about it? Sometimes asking those questions helps me keep motivated.

Mj Shahen: Well, let me give you an example. I see what sometimes happens with Deaf children of hearing parents and I do see that turmoil through the years. I see the struggle. It’s a war between what Deaf people believe and what hearing people believe. And I internalized that debate and that struggle and created a poem. So I’ll give you another example. Amanda Gorman is an example of a person who wants to unite everyone with poetry. She had her poem “The Hill We Climb” where she looked back at oppression, looked back at the things that divided us, the things that were breaking us apart as a country. Now, look at me in that narrative, as part of the Deaf community and the hearing community. There are the parallels that we faced on that journey that Amanda spoke about in her poem.

Celeste Gainey: Well, I guess the most succinct answer would be I keep writing because I know I haven’t exhausted what it is I have to say. And I know I have less time in my life, not more. And I feel that the highest calling of any human being is creative expression. The highest individual calling. I’d like to add that I believe each of us is a child of the time we are born into and, as such, it is our responsibility to bear witness to that time. The foundational bedrock of poetry is to bear witness for those who are yet to come. And so I just know, I want to be doing it till I can’t do it any longer. And hopefully, that’ll be when I breathe my last breath.

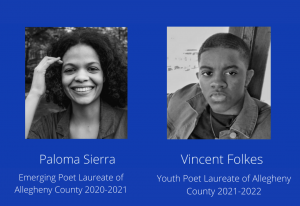

Vincent Folkes is Allegheny County’s Youth Poet Laureate for 2020-2021. Vincent is a creative, entrepreneur, and student at the Community College of Allegheny County. He is particularly interested in music, and much of his work is dedicated to anti-racism

Paloma Sierra, the Emerging Poet Laureate of Allegheny County for 2020-2021, is a Puerto Rican poet, playwright, and translator who is interested in the intersections of poetry and theater. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Dramatic Writing at Carnegie Mellon.

Maryjean (Mj) Shahen is the American Sign Language Poet Laureate of Allegheny County for 2020-2021. She has worked as a trainer and counselor for deaf individuals and has taught ASL at the University of Pittsburgh. Currently, she is an ASL coordinator and instructor at the Community College of Allegheny County and a Communication Support Specialist and Trainer at C.E.M. Communication Services, LLC. Her poetry works to fight stigma and oppression of deaf individuals.

Celeste Gainey, City of Asylum’s Poet Laureate of Allegheny County for 2022-2022, worked in film lighting prior to tackling poetry. She was the first female gaffer to be accepted into the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees. In her poetry collection, the GAFFER, Gainey writes about exploring gender, sex, and identity within this world. She earned her MFA in Creative Writing/Poetry from Carlow University

City of Asylum believes that All Pittsburghers are Poets. With the Poem of the Week series, we seek to increase the readership and appreciation of poetry locally by publishing poems written by residents of Allegheny County of all ages and levels of experience. In partnership with the Poetry Editors at Sampsonia Way Magazine, City of Asylum advances our mission to defend, celebrate, and build on creative freedom of expression. This project received a RADical ImPAct Grant from RAD (Allegheny Regional Asset District).

City of Asylum believes that All Pittsburghers are Poets. With the Poem of the Week series, we seek to increase the readership and appreciation of poetry locally by publishing poems written by residents of Allegheny County of all ages and levels of experience. In partnership with the Poetry Editors at Sampsonia Way Magazine, City of Asylum advances our mission to defend, celebrate, and build on creative freedom of expression. This project received a RADical ImPAct Grant from RAD (Allegheny Regional Asset District).