How to Survive in America: A Conversation with Damon Young

by Kate Rempe / March 9, 2021 / Comments Off on How to Survive in America: A Conversation with Damon Young

Last summer, Damon Young — the writer, critic, and humorist — partnered with City of Asylum to host a six-episode series called “How to Survive in America” in which he interviewed some of his favorite writers about writing, race, living through the COVID-19 pandemic, and everything in between.

Today, the conversations are as prescient and lively as when they first took place in the pandemic’s early days of uncertainty. The series marks an important moment in history: a time when the pandemic atomized communities, when racial justice protests bled on to the streets, when the writers and readers and communities en masse sought new ways of connecting to one another.

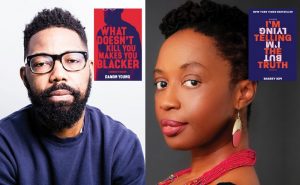

“How To Survive in America Ep. #1 with Bassey Ikpi”

The show was recorded and aired live as Young’s guests Zoomed into his own kitchen for drinks and conversation, serving as an ad hoc happy hour for those of us still reeling from the new world of quarantine. The ease with which he talks with his guests — Bassey Ikpi, Brian Broome, Kiese Laymon, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Nafissa Thomspon-Spires, and Samantha Irby — makes it seem as though we are eavesdropping in on deeply personal conversations instead of the typical visit to Pittsburgh, featuring readings and talks intended for large audiences. In a moment, at the onset of summer, when our collective isolation felt particularly uncomfortable, it was the perfect note of much-needed intimacy, providing an insider glimpse of how writing and community work hand-in-hand.

In the following conversation, Sampsonia Way chatted with Young over Zoom last October — getting the chance to reflect on the series and to get a sense of what it was like behind the scenes.

Zooming Into the Kitchen

What was your favorite part about doing these interviews? And what were some of your favorite things that you got out of them?

My favorite part really was giving all of these Pittsburghers an opportunity to engage with these writers. Now this isn’t the same as actually being in the city for a reading, but the series was a chance for connecting these writers with a whole new world, possibly a whole new group of people who are going to become fans, who are going to buy their books, who are going to support them.

I remember City of Asylum had a thing about a year ago where some of their staff had an Instagram post or a blog where they each talked about their favorite writers or favorite books, and I remember someone mentioning Friday Black. So, I specifically wanted to get Nana Kwame in one of these conversations, because I knew that he had at least one very huge fan here in Pittsburgh, and he might not have been able to interact and engage with them otherwise.

For me, the series provided a bit of professional development too. There were personal aspects where I just had a ball doing this, you know? It was just me kicking it with some of my homies. For some of the tapings, I was drinking, they were drinking. We were just talking about whatever, so there’s that. But also just doing this — this part of the author process, doing the public-facing stuff — is not the most natural thing for me, but doing these sorts of events allows for a sort of muscle memory to build. The more I do it, the more comfortable I get and the more comfortable I am with the rhythms of the audience, knowing where to go with the conversations and kind of just building off of the energy of the person I’m in conversation with.

Throughout the series you seemed so comfortable. It made me curious though: Was it weird at all, having a conversation with your friends that a bunch of other people were listening in on?

As far as it seeming like it was comfortable, I wanted each conversation to feel that way for the guest author, you know? To feel like we are just having a quick conversation where we’re just talking. We’re going to touch on some insider baseball league stuff that’s really esoteric, that deals with rigor, and all the things that go into writing, and going through the work. But it’s going to look like a natural conversation with friends that 300 people just happen to be eavesdropping on.

Community & Love

You mentioned wanting your guests to be introduced to the Pittsburgh community, which I think is really cool. How did you go about cultivating a writing community? Was it an active process or did you just find yourself in it?

The publishing world, I’ve found, is somewhat insular. Because the industry is so white,

I think that disparity cultivates a sense of community, where we stick together, we look out for each other, we try to get each other on this panel and at this festival. So, yeah, that community was a naturally occurring, organic thing. Networking wasn’t a goal I had going into the book. I just wanted to get through it alive. It just so happens that I met a lot of people who, along with being dope writers, are just dope people that I’m legitimately friends with.

Okay, so after watching a couple episodes of the series and a couple interviews that you’ve done outside of that, I noticed the topic of love seems to surround you, your work, and your conversations. I was wondering if you think love and community go hand-in-hand. Was that something you felt in your interviews for the series?

Oh, yeah definitely. There’s love and there’s a mutual respect or mutual admiration there, too. There’s an admiration that even bleeds into jealousy. I mean, I think it’s a healthy jealousy, but with each of those writers who I asked to be a part of this, and many others, their work is so good that I read it, and I’m like “Holy shit! I want to throw my book in the trash right now! I can’t do this.” And you can feel that way, but then you could also take that feeling and use it as fuel, and be like, “They’re so much better than me, so I need to work harder. I need to work smarter. I need to do what I need to do to be as good as they are.”

So there’s that, that definitely exists. But to get back to your question, the love: This is a very difficult time for America, particularly for Black Americans. I think that we recognize that, we see that, we feel it. So, in these moments that we have with each other, we have to kind of let our hair down and build a joke and riff and do all these things. We savor those opportunities. It’s like magic, gold, platinum — vibranium.

On Being Nimble

Yeah, so let’s talk about life in the year 2020. How have you kept your head on straight enough? Were these interviews helpful in keeping you grounded?

I’m fortunate and privileged to have an occupation where I can still work without leaving the house. The pandemic has affected everyone in various manners, but I’ve been fortunate that I’ve still been able to make money. I’ve still been able to do public-facing things even though I’m sitting at my house right now, and that’s a privilege that not everyone has. So I try to stay very mindful of that even when I am feeling, you know, melancholy or worse about our collective predicament.

I’ve always been more of a natural introvert. And I remember when COVID started, we were starting to social distance, and there were some blogs and tweets about “Oh, this is great for introverts! introverts don’t have to talk no one all day long!” It’s like, no. What makes introverts introverted is control. It is not that we hate crowds or hate people or anything like that. We just want to be able to control our environment. And, yes, we need time, we need solitude. But we want to make our own decisions, not that forced solitude.

There’s also the fact that I don’t think I realized how much I need people in order to create work. I work sometimes in City of Asylum and sometimes at the Ace Hotel. In fact, I probably wrote 70 percent of my book while in the lobby of the Ace Hotel. I was staying there until two or three in the morning, at a table, just writing. Meanwhile, there are all these busy parties and stuff going on around me. It became both white noise and also an energy source, but one I didn’t have to engage with. But I could use that energy from the people around me to give myself more bandwidth to work. I haven’t found a way to replicate that yet. So, that has been a struggle. I was not as productive this past year as I tend to be. I’m getting all of these tremendous opportunities to work, to write, and it just so happens to be coming at a time when I don’t have as much to give.

Do you have any advice for other people or writers in the pandemic on how to keep going, or for how to get out of their own head a little bit?

I’m still figuring that out myself. I think you have to figure out what works best for you. We’re in an unprecedented time. I’m still processing everything that’s happening. Things are happening quick, too quick for us to process them. If I could talk to younger writers who are in college or just starting their careers, I think I’d say that this could provide an opportunity to be more nimble, to be more flexible with your work.

But again, I know that it’s hard. This is hard for people. This is a time that drives a lot of anxiety, and that can make things very difficult. I feel that, and I believe that. I’m not going to be the person who’s like, “Well, Chadwick Boseman did all this stuff while he was dying of cancer, so you could — “No, no, no. If you’re not feeling well, if you’re not feeling right, that’s fine.” We’re in an unwell and unright time. It’s perfectly natural to not feel yourself right now, and if your work suffers, then so be it. If anything, I would want people whose work is suffering to find some grace for themselves. Because this is a shitty time and it’s not your fault if you are in a position where you just can’t figure out a path forward right now.

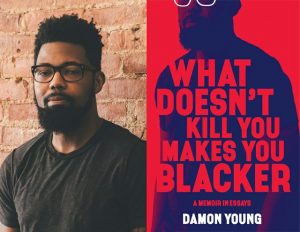

Damon Young is a writer, critic, humorist, and soon-to-be podcaster. He is a co-founder and editor in chief of VerySmartBrothas — referred to as “the blackest thing that ever happened to the internet” by The Washington Post — and a columnist for GQ. Damon’s debut memoir — What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir In Essays – is a tragicomic exploration of the angsts, anxieties, and absurdities of existing while black in America. Today, Damon currently resides in Pittsburgh’s Northside, with his wife, two children.