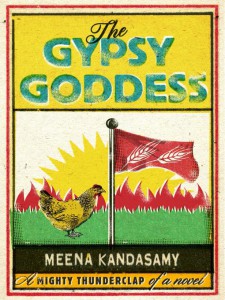

The Gypsy Goddess by Meena Kandasamy

by Meena Kandasamy / September 8, 2014 / No comments

The Gypsy Goddess. Cover design by Studio Helen. Credit: Atlantic Books.

Meena Kandasamy is a poet, fiction writer, translator and activist who is based in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. She is the author of two poetry collections, Touch (2006) and Ms. Militancy (2010). The Gypsy Goddess, published by Atlantic Books earlier this year, is available for purchase here.

_______

The Title Misdeed

When you are high on caffeine and contemporary authors, you begin to question the fundamentals of the publishing industry, which you think owes it to you to make your novel widely read. After all, for the sake of reading widely, you have contributed an unfortunately large amount of your income to the said industry.

Take the title for instance: it has to be catchy, it has to incite curiosity, it has to sound cool when you say it to others. That’s why I settled on this one. Well, almost. It satisfies all of the above criteria.

The minute you realize that the novel is quite unlike the university dissertation, you gain the necessary courage to be experimental. You will soon realize, especially if you have been confounded by Derrida-Schmerrida at college, that a book does not have to be about its title. A title does not have to be about the book. Trust me, they are generous enough to co-exist with each other.

If you ask me upfront, I will tell you that this novel has nothing to do with the title. You are not my agent, anyway. A nice title would have been Long Live Revolution! Or, The Red Flag. Or, as Žižek once said, when asked to share a secret with the Guardian during an interview, Communism Will Win. Sadly, the Communists will be outraged to be glorified in such an archetypal bourgeois literary form such as the novel, which they will contend has been produced for the global market. The other trouble with these titles is that it could get my novel into serious, life-threatening situations. Customs officials in faraway lands could hammer spikes through it or it could by pulped by a paper-shredder in quasi-repressive states. My books of poetry have been burnt. This novel is a delicate darling, and I will not let this happen to her. She has to live. She has to be in love. She has to see the world. For all of that, she has to be named.

In the beginning, I did not want to cheat. I thought of good titles. Tales from Tanjore had an authentic ring to it, but those who picked up such a book would end up disappointed when they did not come across tigers, Tipu Sultan and the Pudukkottai royalty. Then again, Butcher Boys had the sound of a college music band, and little relevance to this novel except reflecting some of the bloodthirsty rage that romps around in these pages. Kilvenmani gave away the location, and a friend said it had a distinct Irish ring to it, so I dropped it as a gesture of goodwill because I didn’t want to mislead my readers. In a similar manner, Christmas Day gave away the date, but that title would make the reader imagine snow and reindeers and pine trees, and the entire seasonal marketing mania, instead of imagining peasant agitations. It would be the equivalent of using the word ‘holocaust’ somewhere in the title, only because you wanted reference to a massacre where sacrificial victims were completely burnt to death. (Christmas Day, did I say? In Jailbird, Kurt Vonnegut wrote of the fictional Cuyahoga massacre that involved industrial action and took place on 25 December. The problem with thinking up a new and original idea within a novel is that you have to make sure that Kurt Vonnegut did not already think of it.) So, I gave up on that title and, for some time, I wanted to name it 1968, the most tumultuous year of recent history, the year in which the central incident of this novel occurs. But Orwell has been there before me with this year-as-title thingy. What’s more painful is that he used my year of birth without my explicit consent.

There go all my titles, and any effort at sincerity. Now I am out of choices. So I settle on the curiously obscure and mildly enchanting choice, The Gypsy Goddess.

I have a great title. I have a great story.

They don’t belong to each other. In this author-arranged-marriage-without-divorce, these two will stay together.

Considering the title of this chapter, I should have technically completed one obligation: unravel the mystery of the title. So, here is the abridged version of the legend of the Gypsy Goddess. Go ahead, read it. These are two minutes of your life that you are never getting back.

The story begins with an epic novelist, who, having penned a racy thriller involving a hetero-normative love pentagon between three men and two women, enjoys enormous popularity and unparalleled critical, commercial and cultural success. At the zenith of his glory, he realizes that his characters have outgrown his epic and have become household names. Every day, he hears of fanclubs being started for his hero, beauty parlours and massage centres named after his heroine, and body-building gyms being inaugurated in the name of his hero’s side-kick brother. And, much as his characters inspire love, they also inspire hate. He witnesses the effigy of his villain being burnt at street corners across the country. He hears stories of men, reeling under the influence of his epic heroes, cutting off the noses of women who have lust in their eyes. This horror, this horror is too much to take. His greatest creation, has labour of love, has turned into a nation’s Frankenstein’s monster. He foresees a future of massacre and mayhem, bloodshed and bomb-blasts, deaths and demolition.

So he fled to foreign shores.

He travelled far and wide and here and there in search of anonymity and, finally, he decided to settle down in a Tamil village where the men had as many gods as their forefathers had found the leisure to invent, where the business of customized, cash-on-delivery idol-making flourished and kept up with the demands of the idol-worshippers, where the men and the women and the children called upon their lord gods every time they had a nervous tic or whooping cough or a full bladder or a mosquito bite or a peg of palm toddy or an argument with the local thug, where they boozed and banged around every day of every week, where they affectionately addressed their fathers as mother-fuckers, where they killed and committed adultery and stole and lied about everything at the court and the confession box, where they coveted each other’s concubines and wives, and where they did all of this because the script demanded it. Evidently, this village in Tanjore was an author’s paradise.

They welcomed him with proverbial open arms. Being unrepentant idol-worshippers, they soon cast the charismatic novelist into the role of a demigod and rechristened him Mayavan, Man of Illusion & Mystery. He was consulted on every important decision regarding the village community. In perfect role-reversal, they told him stories.

The exile ignored their stories for days on end, not allowing any character to have the slightest impact on him out of fear that he would slip into writing once again. But, as was bound to happen, one story about Kuravars, the roaming nomad gypsies, caught his fancy, drove him into a frenzy and rendered him sleepless.

On one night, many many nights ago, seven gypsy women, carrying their babies, strayed and lost their way whilst walking back to their camp. When they came home the next day, the seven women were murdered along with their babies. Their collective pleading did not help. Some versions go on to add that there were seventeen women. Every version agrees that all of them had children with them. Some versions say these women and their children were forced to drink poison. Some versions say that these women were locked in a tiny hut and burnt to death along with their children. Some gruesome versions say that these women were ordered to run and they had their heads chopped off with flying discs and their children died of fright at seeing their mothers’ beheaded torsos run. It is said that after these murders, women never stepped out of the shadows of their husbands.

The novelist, ill at ease, wants to teach a lesson to the village. In one stroke, he elevates the seven condemned women and their children into one cult goddess. He divines that unless these dead women are worshipped, the village shall suffer ceaselessly.

Overnight, the villagers build a statue of mud of Kurathi Amman, the Gypsy Goddess, and say their first prayers. Misers come to ruin, thieves are struck blind, wife-beaters sprout horns, rapists are mysteriously castrated, and murderers are found dead the following morning, their bodies mutilated beyond recognition.

Faith follows her ferocity. Over time, she becomes the reigning goddess.

She loves an animal slaughtered in her honour every once in a while but, mostly, she is content with the six measures of paddy that are paid to her on every important occasion.

This excerpt is reproduced by Sampsonia Way with the permission of Atlantic Books. Copyright Atlantic Books, 2014.