Judith by Abel Fernández Larrea

by Sampsonia Way / September 4, 2013 / No comments

Translation by Alison Macomber

aunt elshvieta was about eighty years old. she was never married. she was small, with short hair and glasses, and out from under them her large nose protruded. at first glance she didn’t seem to have a gender. my father always said that she “looked like woody allen, the american film director.” my mother always scolded my father every time that he, before an imminent visit from our aunt, dropped that comment. but our aunt, on the other hand, didn’t come to visit us very often.

she and my grandmother were sisters, but for some reason they didn’t speak. when grandma died, my father convinced our aunt to come and live with us at haifa. at first, she resisted, but ended up making the trip from birobidzhan to settle in our apartment. she lived with us for a month. at the end, our aunt said that she preferred to live alone and was thinking about moving back to trans-siberia. then my father told her that there was no need to return to any place and he rented an apartment for her close to ours in neve sha’anan.

she sometimes came over for rosh hashanah and other holidays, although none of us followed the tradition. however, she never missed yom hashoah, the day in which we remembered the holocaust. that day, while the majority of the neighborhood walked down the street or went to the synagogue, we made a simple dinner in which my mother prepared little pastries “like in khabarovsk.” our aunt loved these pastries. she could eat ten in one sitting, and then she would say that she felt bad and that she should return to her house. my father always convinced her to stay, and he sent my brother and i to prepare one of the beds in our room for her. at night, my little brother slept with our parents, and i remained in the room with my aunt, which always made me a little apprehensive.

- Abel Fernández Larrea

- Fiction writer, editor, translator, essayist, musician and university professor.

- He has published the fiction book “Absolut Röntgen” (Caja China, 2009). His novel “1991” remains unpublished, although awarded with the Frónesis (2012) Creative Writing Grant from Asociación Hermanos Saíz, Cuba. Also in 2012 he won the Matanzas City Foundation Award for his short-story volume “Berlineses”.

- His stories and essays have appeared in the Cuba literary magazines Matanzas, El Cuentero, La Letra del Escriba, El Caimán Barbudo and Voces.

- Read more…

my aunt talked in her sleep. most of the time she said russian slogans, as if she was haranguing workers in a rally. my father told me that she had been commissar, working actively after the war. also, he told me that because of her, many had been expelled from the party, which was the equivalent of losing it all. people even went to the gulags because of my aunt. meanwhile, she had been awarded the order of lenin.

other times, when she slept, she spoke in yiddish. these dreams seemed older, from before or during the war. they were convulsive dreams. i didn’t understand yiddish very well; only a few words. from what i understood, she seemed to talk with someone, saying “my love, my love, don’t do it.” sometimes she said the name of my grandmother. other times, she repeated a name: rudolf. several years passed before i could find the story, before i understood the cause of aunt elshvieta’s dreams.

- The Writer Speaks

- Interview by Justo Planas

- “I do not identify so much with my generation, or at least with that generation to which you refer, the more contemporary. We have different perspectives and preferences, I could say that even different systems of ideas.

- ”

then i was about to finish high school. i had read something about the great war, about the massacres, the evacuations, the death camps. i was interested in everything related to the german-romanian invasion and the resistance of the partisans. i thought that maybe aunt elshvieta, who had lived during that time, would know more about it.

one day, after i left school, i decided to stop by her apartment on my way home. my aunt wasn’t there, so i had to sit on the steps and wait for her. after a while she appeared, laden with shopping bags. she was happy to see me and i thought that was a good sign, so i helped her carry the bags. my aunt, given her age, climbed the stairs more energetically than i did. i assumed this was because her habit of walking from one place to another when she was a commissar. we put the bags on the table. my aunt wouldn’t stop looking at me and made comments about how much i had grown, even though it had only been a month since she’d been to our house.

–but how big you are, misha! –she said–, every time i see you,you look more like your father!

then she offered me a snack and began to prepare orange juice. i walked over to her while she cut the oranges. she had a steady hand. with one chop she’d part the fruit into halves.

–aunt –i said, finally daring to speak–, can you tell me about the great war?

her countenance changed. the knife stopped, skimming the surface of the orange. my aunt shook her head and continued driving the blade into the fruit. then she put the knife down and began to squeeze an orange half in her hand. her pulse was shaking.

–what do you know? –i said at last.

–i don’t know… anything.

–our region was very far from the front. there is little i could tell you.

she finished squeezing the oranges. she added water and a little sugar and served me a glass with a cookie. i wasn’t going to ask her again. i drank the glass in silence, nibbling the cookie between sips. after a while she had forgotten the incident and she repeated over and over that she was delighted by my visit. when i was leaving, she insisted that i bring some oranges to my mother.

for a month i frequently went to my aunt’s house. i didn’t ask her questions, but i knew that she was hiding something behind her reluctance toward this topic, and i harbored a secret hope that she would at some point decide to tell me. she, on the contrary, distracted me by inviting me to have snacks, sometimes tea and donuts, and other times juice and cookies. occasionally she would tell stories, but these were always about life in the autonomous region of trans-siberia. at first, they didn’t arouse my interest. then i became accustomed to her stories of workers building their lives in adverse conditions.

one day i forgot to visit her. nothing special, only i had started to think about my exams and i gradually turned my attention to other issues.

that year aunt elshvieta was not with us on yom hashoah. she called by phone to tell us that she was indisposed, and that she was very sorry. my mother told her that she would save some khabarovsk cakes for her. even that didn’t seem to cheer her up. after dinner, i went to my room to do homework and i was surprised to be missing my aunt, even if she did talk in her sleep in the middle of the night.

a week later, my father had to bring aunt elshvieta to the hospital. there they did tests and diagnosed her with a severe heart condition. they placed her in long-term care and they discussed the need to operate. mom and dad took turns staying with her. i was so busy with my exams that i was only able to visit her once. when i did, she was sleeping. i stayed a while, watching her dream, in case she woke up. she didn’t wake up. nor did she say a word.

summer came along with the end of high school. i was concerned about college, and leaving home. my aunt didn’t get better, but she expressed her reluctance toward any operation. at the beginning of elul they decided to send her home, to see if a more familiar environment would settle her. we put her in my room, in my brother’s bed, and we brought some clothes and a box from her house that she insisted upon having.

once she arrived at our house i felt she didn’t take her eyes off me. i was a little guilty about not visiting her frequently, and because i hadn’t seen her that much while she was in the hospital. that night, while she was sleeping, she spoke in yiddish the entire time. again and again she repeated the same words, the same names: that of my grandmother and the so-called rudolf. when i woke in the morning she had already gotten up. she seemed to have been watching me sleep for hours.

–misha –she said to me when i opened my eyes–, come here, come with me.

i stretched with a big yawn. i jumped out of bed and sat on the edge of hers.

–i am going to tell you something that nobody knows. something that i have kept quiet for a very long time.

i got the creeps. finally I would know the history of the guerrillas fighting against the nazis.

–you see that box, the one they brought from my apartment? – my aunt pointed at it without taking her eyes off me–. bring it to me, please.

it was a medium-sized box, lined with leather. the hinges creaked when i took it, and when i dropped it on the bed, the lid jumped up. inside were piles of paper, cards, and medals. the lenin award was there, which cost so many expulsion from the party. also, there were many photographs. aunt elshvieta appeared in all of them, dressed in a grey uniform and military boots. in some she was walking through the trans-siberian snow, in others she was in elegant offices, shaking hands with party leaders, or being awarded for her political work. in all of them she could be easily recognized: her short hair, her lack of makeup, the hard look behind her glasses. however, one photograph looked nothing like her. i only recognized her through a familiar appearance, and because the photograph looked like pictures i had seen of my grandmother. it was dated 1941, when aunt elshvieta was around twenty years old.

–ah, sweet youth –she sighed at the sight of the picture–, here i was before the war. i was eighteen.

in the other photograph, she appeared with my grandmother, but wore a severe look and had short hair.

–this was around the days we came to birobidzhan –she said–, it was a such long trip on the train, very long.

her words gave me doubts. until then, i had thought that they, my grandmother and my aunt, had always lived in birobidzhan. i kept looking through the papers. suddenly, i couldn’t believe it, in the bottom of the box was an einsatgruppen d stamp, the kind originally put on the collar of a jacket. i recognized it instantly because i had seen it so many times in history books. the stamp had an almost black mark on it that seemed like it was part of the fabric.

–oh rudolf, rudolf! –my aunt sighed, her eyes turning glassy.

i put the stamp back in the bottom of the box and lowered the lid. aunt elshvieta bowed her head and covered her face with her hands.

- Alison Macomber

- Literary translation/editorial intern at Sampsonia Way Magazine. Her work “El Guepardo,” as photographer of Mexican Masks on the streets of Taxco, was published in Generation Magazine. She is a writer for the “I Write: The Movement” Foundation. Graduate of Saint Vincent College with B.A.’s in English and Spanish. She translated Burmese poet Khet Mar, as well as a collection of Miguel de Unamuno’s poetry in a Literary Translation Workshop at Saint Vincent College. Her thesis project about the silent voices of women in late 18th century America was entitled “Founded on Muffled Fact: Silence Speaks in The Coquette.”

–in 1941 –she began saying– your grandmother and i lived in the village of bilivka, near vinnytsia, in ukraine. we were both diligent students of the regional school, and we were preparing to go to college. but the blitzkrieg came. the men had to go to war; only the very old and children were left. us women were left in the village to do all of the work. we cut firewood, carried the water, and fed the animals.

–one morning we heard gunshots near the village. the war was advancing toward us. we were all very afraid, so we hid in the basement of the rabbi’s house. we were there, huddled, for two hours, thinking that at any moment the soldiers would arrive. then it was all over. there was a long silence, we didn’t know what had happened, and fear prevented us from going and finding out. in the afternoon it was very hot so i decided to go to look for a bucket of water. there was very little water in the well, so i went to the river, carrying two buckets instead of one.

–i was coming back from the river when i saw him, lying motionless under a fir tree. he was a young german soldier, and his leg was wounded. when i approached him he began to tremble. he said things that made no sense. i hesitated a couple moments, thinking about whether i should continue on and leave him lying there or if i should stop to help him. i finally decided to give him a little bit of water, cleaned the wound on his leg, and bandaged it using my handkerchief.

–i secretly went to see him every day for a week. i brought him food and water that i stole from the pantry, and cared for his wound as we conversed. his name was rudolf and he was lieutenant of einsatzgruppe d, but at that time i didn’t know what that meant. he said he was against the war, that he did not want to kill anyone and that he only did so out of obligation. he said that in the year 39 he had begun to study literature, but then they sent him to the army and he had to leave the university. he would recite shiller’s, hölderlin’s, and novalis’ poems, and when doing so his blue eyes would shine intensely.

–one day he wasn’t there. with my care, his wound had healed and he could already walk. it saddened me that he left without saying goodbye, but i thought that it was better for him to return to his companions as soon as he could. however, the days passed and i found myself thinking about him most of the time.

aunt elshvieta approached the box. she opened it and began to review the photographs. she ran her hands over each one and then set them aside. she stopped when she came to the picture of her and my grandmother. she spent some time looking at it in silence. then she turned and looked for the stamp at the bottom of the box.

–some days later we heard the shots approaching us again. this time we heard very intense sounds like heavy artillery and tanks pushing through the forest. we went back to the basement to hide, and there we heard sounds of tanks coming closer. then we heard them stop, already in the village, and then the sound of boots and orders given in german. they were looking for us. the women sobbed, trying to prevent their children’s crying. the rabbi led the old in prayer. your grandmother and i were clutching each other in a corner. not even the worst could separate us.

–it wasn’t long before a soldier discovered our hiding place. violently they pulled us out, shouting insults in german, and took us to the center of the village. a boy tried to escape and one of the soldiers fired. a flash. the boy fell forward, dead, and his mother began to scream and hit the soldier, as he held her off with a rifle. another soldier grabbed the woman and pushed her to her knees. then an officer drew his gun and put it to the woman’s neck. only a single shot. the woman fell headlong into the dust. i recognized the officer when he raised his head to put away the gun: it was rudolf.

–they told us that the next day they would take us to vinnytsia. from there, a freight train would take us to another place, where we would work for the reich. we would sleep there that night, and would leave very early the next morning. then they took us to a barn and locked us up inside.

–during the night some soldiers entered. they were drunk and laughing. they took the young women, telling us that there was a party. before leaving, a soldier asked if anyone had a musical instrument. matvéi, an old man, said that he had a violin. they also brought him with us.

–the barracks had been mounted in the rabbi’s house, which was the largest one in the village. in fact, they had the party there. the house was full of drunk soldiers who began to whistle at us when we arrived. they told matvéi to play. he took out his violin and began playing a polka. the soldiers took us out to dance. they offered us cigarettes and cognac. i was looking at all of their faces for rudolf’s blue eyes. i didn’t see him.

–rudolf appeared quite later that night. many of the soldiers were lying in the corners, sleeping off their drunkenness. others had gone, leaving with the last girl they danced with. some of them tried to separate me and your grandmother. one soldier insisted upon leaving with your grandmother, but i wouldn’t let her go. the soldier laughed with the others. “what am i to do,” he said, “it seems that i can have two fish at the same time.” the others laughed. they told him to share them. they tried to peel me from my sister, but we were seized by force and they were drunk.

–then rudolf entered. he asked what had happened and the soldiers explained it to him. he ordered them to leave me in peace. i thought that we would be saved, in spite of everything, because of rudolf. he came up to me and looked at me with that gleam in his eyes. i let go of my sister. “and what do we do with the other?” asked one of the soldiers. he was referring to your grandmother. “you can take her,” said rudolf. i screamed. i didn’t want them to take your grandmother. i tried to grab her again, but rudolf stopped me, holding me back forcefully. the soldiers took her and i remained there, crying.

aunt elshvieta covered her face with her hands. i realized that she was reliving events that she had long kept hidden. i had never before heard anything about what had happened there. not even from my grandmother.

my aunt cried, squeezing the stamp in the palm of her hand. then she told me how rudolf had tried to take off her clothes, and that when she refused, he became enraged and began to hit her, yelling that she was a jew and that her entire race was going to die; that hundreds had already been killed in vinnytsia; that he, with his own hands, had shot more than twenty. then he took my aunt by force and brought her to the rabbi’s room, where he continued hitting her and harassing her, before he tore her dress, overpowered her, and raped her.

–when he was done, i cried uncontrollably. i was badly beaten; my nose bled. My entire body hurt and i loathed myself and was very afraid. he lit a cigarette and smoked it on the edge of the bed in silence. when he was done, he threw the butt on the ground and crushed it with his boot, then he fell upon the pillow and fell asleep. i didn’t want to move for fear of waking him, but i had to get out of there. i had to flee. at one point i mustered enough force and courage and got up very slowly. he didn’t wake up.

–outside only drunk soldiers were sleeping. no one moved. i went out into the night, half-naked and bleeding. in the middle of the darkness i tripped over a pile of firewood. i feared that that the noise would wake the soldiers, so i groped and searched for an ax to defend myself. no one woke up, but a few steps away i heard a whimper. it was my sister; i recognized her voice even though she whispered. i approached her. she also was beaten and her dress was torn. she had been assaulted by several soldiers. her mouth was broken and her black eyes wept with fury, but they were without strength. an infinite rage came over me. i tightly grabbed the ax.

–in the room, rudolf was still asleep with his head cocked on top of the pillow. in that moment rudolf looked like he did under the fir tree, that injured boy who recited poetry. but nothing could erase the newer images of rape, humiliation, and beatings; the ease and coolness with which he had shot the woman; how he said that all of us jews were going to die; that he had killed at least twenty. i clutched the ax in the air and let it fall like a broadsword.

aunt elshvieta imitated the movement of the ax in the air. then she stood for a moment, with her head down, staring at her hands. in them was the stamp of einsatzgruppe d, with the mark almost as black as dried blood.

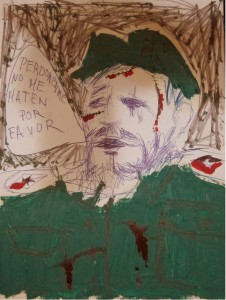

i imagined my aunt as a judith, a heroine who saved her village from invaders, decapitating their general. i imagined her brandishing the blonde-headed german lieutenant. bringing his head to her friends locked in the barn and freeing them. my aunt remained silent, bowing her head with her eyes fixed on the stamp.

–and what happened next? –i said without being able to resist the temptation of knowing if what i imagined was true: my heroine aunt freeing her village.

–then i went to look for your grandmother, – she said – i helped her to her feet and we slipped into the forest. we walked several days until we found our troops. we were put on a military train bound for birobidzhan and khabarovsk.

i looked at my aunt, surprised. that wasn’t what i expected.

–but, and the others? –i said without understanding anything– and old matvéi? and the other girls? and the others locked in the barn?

aunt elshvieta sighed. she put the seal away into the box.

–the others? we never knew –said my aunt as she closed the lid– imagine, if i would have freed them, we would have all been discovered! there were too many people.

Edited in English by Joshua Barnes

__________

All facts and characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Los hechos y/o personajes de esta historia son ficticios, cualquier semejanza con la realidad es pura coincidencia.

Leer en español

__________