Summer Bells by Jhortensia Espineta Osuna

by Sampsonia Way / August 26, 2013 / 1 Comment

Translated by Alison Macomber

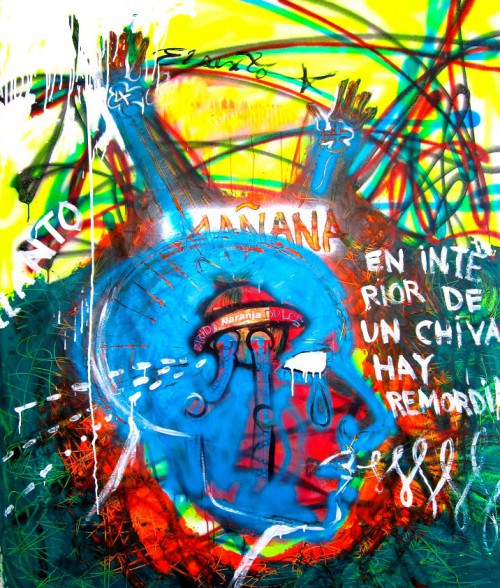

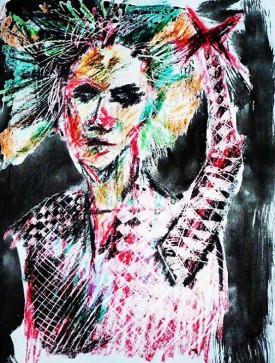

Painting by El Sexto.

Dunia, your daughter, doesn’t leave her room, or the room that you both share and that you all shared with your mom and your grandmother until they decided to die last June, one after the other, so August wouldn’t remove the liquid that remained between their skin and bones.

Through the window, the neighborhood parades by, wearing their Sunday clothes. Others only pass with their nylon bags to begin the week with whatever is in the bag.

It’s the end of the month; you’re trapped between the window and the cracks on the floor where the ants have made small colonies. The living room is large, with only corroded furniture, incapable of filling the territory. The painted wall exhibits your title “Doctor of Medicine,” along with your white coat and your stethoscope. The three things hang on the thickness of the adobe wall of lime and cement.

- Jhortensia Espineta Osuna

- She has published the book of short-stories Zona de Exorcismo (Ácana, 2006). Her texts have appeared in the Cuban literary magazines Antenas and El Caimán Barbudo.

- Espineta Osuna takes refuge in one of the upper floors of one of the few tall buildings of Camagüey. From there, with explosive silence, like a gladiator illuminated by her own letters, she has been writing a novel for years. Despite her profession as a publicist, she is suspicious of mass media when it comes to reveal the secrets of her own narrative.

- She resides in Camagüey, Cuba.

- Read more…

You don’t move from where you stand and you look at the old man with the dog on the front sidewalk. Since his son arrived, the old man is in better condition. His ribs are no longer visible underneath his skin, and maybe he doesn’t need to kill cockroaches at night, filling the floor with insects and gobs of spit.

You still haven’t moved from this spot; you continue standing there between the cracks on the floor. The old man pets the dog’s belly as he lifts his leg and urinates on the wall.

‒Bringing that dog here cost two thousand dollars!

Your whisper surprises you and you look out the window.

The old man enters behind the dog, and then he closes the door behind him.

‒A dog!

The old man’s son arrived in a car one night, filling the block with noise and music. When he left, he was just a boy lacking many aspirations other than seeing his father killing cockroaches and spitting everywhere. Now he is a mixture of grease and odors; with him he brought a fat woman as greasy and odorous as he and they filled the house with furniture capable of holding him, his fat woman, and an entire family of smelly, obese white people.

The first time the fat man saw Dunia he offered her a soda. They spoke intensely about her slenderness and her blue eyes, but mostly about her slenderness and how much she had grown. He called the fat woman so that Dunia could meet her; to know about her obesity and the little Spanish she spoke. But you didn’t pay attention to that; in the end you were just old neighbors.

One night they went out. Dunia returned a little dizzy. You had never seen her so playful or perhaps you had never paid attention to her stature, nor to her breasts. It wasn’t simply her fifteen years; but that they were thin, long, and well-developed years, even if the ration basket was limiting her genetics.

But it was too much: Your mother, your grandmother, Dunia, and your plans to find a job abroad, even if there are or are not black people like there are here. By working abroad, you would be able to repair the floor, full of cracks, and fill the spacious living room with furniture.

The second time, the fat woman almost carried Dunia to the house. You smiled at her at the door. She carried a shopping-bag cluttered with stuff —so many things that the next day you could only caution her about the side effects of drinking.

Art by El Sexto.

‒It was only two beers, mom.

And dancing. You knew later how much they had danced.

‒They are so much fun.

‒It is the money that makes smiles ‒you said between grimaces, not only because of her alcohol intoxication, but because of the fat couple’s caring and tennis shoes and jeans and perfumes.

‒Thank goodness they didn’t forget the favors I did for their old man.

The following days everything was the same; your daughter barely came through the house to bring you food and give you a kiss. The fat couple smiled at you from the car, waiting for Dunia to get in to go any place in the city that would permit two, insatiable fat people and a teenager.

‒Tomorrow they are leaving.

Dunia almost jumped from the door of the house to the car, while August evaporated the city.

They brought her back in the small hours of the morning. This time she wasn’t stumbling, but she wore an idiotic grin and her eyes were almost motionless. She went to her room and threw herself onto the bed. They gave you an even bigger smile, with an even bigger briefcase.

‒She’s a good girl, take care ‒said the fat woman in her ridiculous Spanish, and the fat man nodded his head.

- Alison Macomber

- Literary translation/editorial intern at Sampsonia Way Magazine. Her work “El Guepardo,” as photographer of Mexican Masks on the streets of Taxco, was published in Generation Magazine. She is a writer for the “I Write: The Movement” Foundation. Graduate of Saint Vincent College with B.A.’s in English and Spanish. She translated Burmese poet Khet Mar, as well as a collection of Miguel de Unamuno’s poetry in a Literary Translation Workshop at Saint Vincent College. Her thesis project about the silent voices of women in late 18th century America was entitled “Founded on Muffled Fact: Silence Speaks in The Coquette.”

As soon as they left, you opened the briefcase; you were examining all of its contents. Perhaps they would take those clothes into account the next time they select someone for a job abroad. Those clothes and those perfumes relieved the burden of carrying two old women for years, and returned your tall daughter with the blue eyes to you.

When you counted the money Dunia approached with her hands on her face.

‒My head hurts really badly.

‒Your entire body must hurt.

‒My head more than anything.

‒Lie down, and it will pass.

Almost from the beginning, you knew it wasn’t just beer. Her clothes carried a dry and thunderous odor of marijuana. You smelled her mouth many times while she was sleeping, and you sat on the bed and looked at her.

You felt an intense cold in your stomach, not from the smell of marijuana, not even from the remains of dried semen caught in her pubic hair, but because you remained unchanged and even felt pity for Dunia that she bore a weight so heavy or, perhaps, that your daughter was capable of maneuvering on top of the fat man.

Now you’re at the window; you don’t have to go to the market to haggle or wait almost until the end for the rebates. Sunday is all yours. Tomorrow you will go to work with much more eagerness to elude your patients’ clinical, delirious diagnoses, more because of scarcity than their pathology, and to actually prescribe them the dose of humor that they need.

Dunia, from behind, surprises you by striking the bars one by one with the fan; you look at her and she smiles at you.

‒They left you a suit that’s beyond imagination.

‒I already saw it.

‒Come here so you can try it on.

The two crouch down to rummage through the briefcase.

‒What would have happened if she surprised you with him?

Dunia looks at you and wipes away the sweat on your brow.

‒I never slept with him.

‒Then who?

‒It was with her.

You keep looking and begin to rummage around in search of the suit.

‒The semen that you cleaned off of me was from the dog.

The suit is the color purple; the blouse has a print in the same color and in black, with matching shoes. It is a nice suit, only it has to be taken in.

Edited in English by Joshua Barnes

__________

All facts and characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Los hechos y/o personajes de esta historia son ficticios, cualquier semejanza con la realidad es pura coincidencia.

Leer en español

__________

One Comment on "Summer Bells by Jhortensia Espineta Osuna"

An excellent rendition of a wonderfully-written short story. The translation doesn’t betray the Cubaness of the original. This is by far one of the most striking and compelling stories in Espineta’s book –a must read for whoever is interested in what’s coming out of Cuban literature these days.