Breaking News by Jorge Enrique Lage

by Sampsonia Way / August 1, 2013 / No comments

Translated by Guillermo Parra

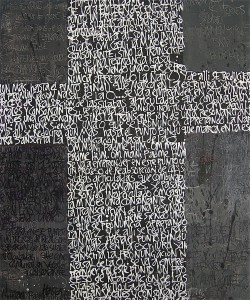

Acrylic on Canvas by Luis Trápaga

She doesn’t mean a thing to me, and yet

I’ll pursue the mystery of her death.

-Rodolfo Walsh

They say the freeway will crisscross the city. What’s left of the city. By day the bulldozers advance, sweeping away parks, buildings, shopping centers. By night I wander close to the sea, amid the ruins, the machinery, the containers, trying to catch a glimpse of the magnitude of what’s coming. There is no doubt the freeway will be something monstrous.

This is what happens with freeways: It doesn’t matter where they might pass through, at each side the desert begins to grow (like an intention of space, a possibility).

I run into him again tonight. I call him Autistic Man. At one time he was a nerd, a geek, a freak in his own manner. Now he is beyond all that. I find him sitting beside some skeletons of American cars that must be more than a century old. He has made for himself a tangle of various colored cables from which he gets enough light to read the latest issue of Wired Magazine. I gesture hello to him and keep walking. Someone should make a documentary about him.

A mysteriously open container. I shine a match on the metal door. A whole bunch of stickers that say: SNACK CULTURE. Outside, on each end, in even bigger letters, it probably says the same thing: SNACK CULTURE. Inside there is a corpse (there has to be).

- Jorge Enrique Lage

- Editor of the magazine El cuentero and the publishing house Caja China of the Onelio Jorge Cardoso Literary Training Center. He has published the short-story books “Yo fui un adolescente ladrón de tumbas” (Extramuros, 2004), “Fragmentos encontrados en La Rampa” (April, 2004), “Los ojos de fuego verde” (April, 2005), “El color de la sangre diluida” (Letras Cubanas, 2007), “Vultureffect” (Unión, 2011); and the novel “Carbono 14, una novela de culto” (Altazor, Perú, 2010). Read More.

“Anything else?” asks Autistic Man.

“Tons of boxes, boxes, boxes.”

“I mean, are there any other bodies?”

“You and I are here, right?”

“Other bodies. Other bodies.”

He is almost asking me for them. I tell him:

“I don’t know why there’d be any.”

A helicopter patrol crosses in front of the moon. When they disappear, Autistic Man stares at me with his expressionless face and says:

“It’s always the same. You, me, and a dead woman.”

Dressed like a queen, or like a whore dressed like a queen, with a gown and sharp heels and a Vuitton purse, even the blood beneath her turns out to be an expensive puddle.

She had gotten dressed to go out with someone, maybe to a red carpet, maybe a party for the rich and famous, something that definitely went wrong. Her hair is messed up, make-up intact. She’s not a young woman. She’s past her forties but still maintains some traces of being a plastic girl. She has jewels, but no money. She surely had many friends and unpredictable lovers. You can infer all sorts of stories just by looking at her sprawled on the floor of the container. Of course, it’s Vida G. The Cuban-American model, singer, actress… Her face still pretends to be unmistakable.

- Guillermo Parra

- Guillermo Parra (b. Cambridge, MA, 1970) is a poet and translator who lives in Pittsburgh. He has published the translation José Antonio Ramos Sucre, Selected Works (University of New Orleans Press, 2012), which was included by World Literature Today in its list of “75 Notable Translations 2012.” Since 2003, he has written the translation blog Venepoetics. He recently edited and translated a dossier of 20th century Venezuelan poetry for Typo Magazine, entitled ‘Portable Country — Venezuelan Poetry: 1921-2001’. He is the author of Phantasmal Repeats (Petrichord Books, 2009) and Caracas Notebook (Cy Gist Press, 2006).

“We’ve got to do something. Let’s find a phone,” I suggest. “Let’s find a damn phone. Let’s go to Nokia, that little city in Finland.”

But we don’t move. We begin to argue about whether one of us should stay and take care of Vida’s corpse (maybe examine it closely). And in the middle of that necrophilic argument the mist reaches us. The mist we hadn’t realized was moving toward us.

For a moment, when it’s almost grazing our noses, this is what we see: What seemed like a veil of water is like a front of electronic ether, a static-filled screen, a crystal that liquefies the landscape we see through it. It quickly passes over us and provokes no sensation at all; in any case the effect vanishes in a moment and in its wake everything remains the same as before, though slightly more illuminated and in various shades of grey.

Autistic Man and I look at each other. Autistic Man says he knows where to find a stretcher. I think: The only place that hospital junkyard exists is in his mind.

We place the dead Cuban-American in a metal stretcher with wheels, and roll down to the checkpoint that guards the zone. The guard comes out and shines a flashlight on us:

“Stop there! Who are you?”

We don’t answer that question.

Theory of reflective silence.

“How’d you get in here?”

“We’ve always been inside,” says Autistic Man.

“What are you carrying?” The guard comes closer to inspect the stretcher. “People come here to steal construction material, and you…”

“Do you recognize who it is?” I ask him. “Look closely.”

He focuses his glance. He’s fat, pathetic, about ten destroyed years older than Vida, and seems to need, at the very least, some eyeglasses.

“Such a delicious cougar,” he admits. “It’s obvious she’s a capricious devil. Things like this are what make my heart suffer.”

“The heart magazines come with waiting lists for transplants,” says Autistic Man for no specific reason. “You have to read all types of things.”

The guard looks at him with a mixture of confusion and reverence.

“Hey, I’m on a waiting list for transplants.”

“So what are you doing here?” I ask him.

“I’m waiting for them to finish the freeway. The pay is shit, but they pay. I was a colonel in the Armed Forces, did you know that? And look where I’ve ended up. At a checkpoint watching TV all night.” The guard looks at the corpse again, cracks his fingers. “Now I know! She’s the one from the newscast.”

Acrylic on Canvas, by Luis Trápaga

We enter the checkpoint. The National Television Newscast is playing on a portable black & white TV, and there she is. Live and alive. Vida G is the main female newscaster. With devastating cleavage, she tells us about a tidal wave in Asia. But she’s also the main male newscaster. Vida G with a thick mustache, her hair pulled up under a wig, her breasts flattened and invisible under a suit and tie. And she’s also the weatherwoman: Wearing another suit, with different, tighter pants, the same voice moves a hand across the map, pointing out high temperatures.

And up next is Vida G as the smart young sportscaster who chats with a greying baseball analyst who is also her. And then Vida G in the cultural section: Her face rounder, a wide smile, disappointing blouse. And Vida G the newscaster who presents the features by Vida G, the correspondent who reports from all over the world. Go ahead, Vida. Thank you.

“This means something,” the guard says.

His eyes grow wide and his face pale. He has seen a clear sign in the superimposition of so many news images with the body we’ve just found. This surely has to do with him; lately all the guns point in his direction. He was waiting for her, she’s finally come to find him. The fatal hour is at hand. (But something else comes to mind for me.)

“Maybe it’s not what you imagine. Without wanting to detract from your terminal conjectures, with the utmost respect, I think it could actually be quite the opposite. It could be an opportunity to have a new heart.”

The guard blinks, perplexed.

“Her heart? To put on her heart?”

“Right now, before it gets cold. If what you say is true, you don’t have anything to lose. On the other hand, if everything works out…”

“But how am I going to live with a woman’s heart!”

“If women can, colonel, why can’t you?”

He remains silent. Pensive, he puts his hand on his chest and taps it a few times.

Autistic Man and I look at each other. Autistic Man tells me he knows where to find a stretcher.

I think: He won’t dare. I’m sure.

And yet, he lies down without hesitation on a metal stretcher beside Vida’s and closes his eyes and acts like he has made a decision and more than that, as though he were anesthetized.

“Scalpel,” I tell Autistic Man.

Acrylic on Canvas, by Luis Trápaga

I try to concentrate, staring fixedly at the donor. I tear the dress’s fabric. Of course she’s not wearing a bra. I move her left breast slightly to the side. If I puncture the wrong spot a stream of silicone might leak out, I could find a stray bullet or a wad of bills, anything could happen. I make the incision. I open her up. I dig deeper. (I’ll probably have to use a saw.) I pull apart the ribs and the plastic. Now I separate everything that’s not important. The heart is left visible. I cut all the tubes and cables that hold it. I stick my dirty hands into the still-warm chest that keeps getting warmer…

It burns. (A perfumed smoke rises.) I pull out Vida G’s heart.

“How disgusting,” Autistic Man says at my back.

I hold Vida G’s heart as though it were the most fragile thing in the world. It’s moist. It’s small and feminine. It’s an erotic toy. It’s got batteries: It vibrates in my hands, or maybe it is my nerves that are transmitting electricity into it.

Suddenly the heart beats. A single pulse. A strong pulse. I turn toward Autistic Man.

“Did you see that?”

“No.”

I watch the heart for a few seconds. It doesn’t beat again. I squeeze it a little. Nothing. I ask Autistic Man to hold it and I pick the scalpel up once more.

“Don’t let it fall. Hand it over to me when I tell you.”

“Why would I want to keep this? She doesn’t mean anything to me.”

“That’s right.”

I approach the other body. He has already taken off his uniform shirt and displays his flaccid, sunken chest, with a few solitary hairs that look like twisting worms. I feel a heart, my own, beating strongly. I look at Autistic Man, I look at the heart, that piece of woman in his hands. I look at the chest that’s about to be opened. I lift the scalpel. I let it fall. I step back.

“I’m sorry, colonel.”

He gets up. He starts to button up his shirt.

“I knew you wouldn’t dare,” he says.

Or maybe I will.

The colonel lies down without hesitation on a metal stretcher beside Vida’s and closes his eyes and acts like he has made a decision and more than that: As though he were anesthetized.

“Scalpel,” I tell Autistic Man.

1. I open her chest, take out the heart.

2. I open his chest, take out the heart.

I toss heart number 2 in the trash. I put heart number 1 inside him.

I close his chest while Autistic Man closes her chest.

“She means nothing to me,” he murmurs, “and yet here I am filling a hole with freeway sand. She means nothing to me, and yet here I am sewing up her damaged body with wire.”

I tell him to shut up, because, after all, he’s the only one who understands what he’s trying to say. That’s one of the reasons I call him Autistic Man.

The military operation finally ends.

“Ready, colonel.”

He gets up. He starts to button his shirt.

“Now let’s bury that bitch,” he says.

He doesn’t need to call the cops anymore: Now he is the police. He tells us about other buried bodies, of a place he knows about, where people go (not the guys who pay shit—the guys who really pay you) to get rid of bodies at night.

Prostitutes. Beggars. Witnesses. And bodies the helicopters toss, as well, and desperate fugitives that bury themselves, digging with their fingernails. Corpses nobody will ever find, the colonel assures us. All this, as far as the eye can see, will soon be covered by tons of asphalt. All of it.

- The Writer Speaks

- Interview by Claudia Apablaza.

- “I narrate what emerges just behind the words, with that substance that remains, like a discomfort, like indigestion, inside the story you are telling. I am not the right reader to give definitions. The mixture and recycling seem to be a good starting point.

”

The three of us walk in silence. Leading Vida G’s stretcher through dirt trails full of pebbles. We pass by trucks with immense wheels, we edge along giant deposits of water or cement. You can see even further: The reach of a satellite’s images, future Google maps. I think of the infinite rails that depart from the nearby continent, an infinity of shining lights in the nightmare of concrete that approaches, roaring through the sea. It will pass over this strip of deserted land and keep going, heading south, toward the sea again.

The colonel looks around in the bushes, beneath some planks, and a pick and shovel appear under the light of the moon. Those are the only tools we need to hide the transplant. The true and definitive evidence of the transplant.

The colonel shows me his chest. The wound is an inflamed incision, of reddish color, crossed by a stitching of wires about to burst.

“Isn’t this botched job proof enough?”

“No,” I tell him. And I know I’m right.

“Shut up. Let’s dig the hole.”

We dig. The colonel digs with passion, with pride, with brutality. He deploys an otherworldly energy.

We stop at an acceptable depth. The colonel carries Vida G and drops her at the edge of the hole.

“Does anyone want to say a few words?”

I shrug my shoulders. I don’t even know who she is. It would be best to speak of a theory. Or contradict it. But I don’t say anything. (Vida’s Life: From Havana to New Jersey to half the world’s swollen ocular globes at the speed of those American cars that never stop on their way back to Havana once again and forever and…)

Autistic Man, as if he didn’t want anyone else to hear him:

“No one will know where to find you anymore, Vida Google.”

“G,” I correct him pointlessly.

The colonel lifts his hand:

“Well I do have a few words. What I have to say is the following,” he unbuckles his belt, opens his fly, pulls down his pants and his ragged underwear. He lifts Vida’s dress, takes off her lace panties, throws them to the bottom of the hole. “Even though she’s dead, this bitch is gonna know what a Cuban stud is.”

The colonel’s hand starts to negotiate an erection.

“I don’t think it’s the time,” I tell him.

Autistic Man touches my shoulder and hands me a magazine. It’s the issue of Playboy with Vida on the cover and in the centerfold pages. I really don’t know where he gets these things.

“You’ll see, you’ll see…” kneeling and uncomfortable between Vida’s open legs, the colonel fondles her closed chest, sucks on her bloody nipples, sticks his fingers in her vagina while he strokes his penis, stretches it, squeezes it…

It won’t get hard.

I skim through the Playboy. The articles, the interviews, the fiction. I think of the places where those sticky pages have been read (and how they’ve been read, and by how many hands). Offices. Garages. Basements. Farms lost in the middle of remote roads. Nocturnal checkpoints throughout an entire journey amid ruins. The magazine had time to travel, from hand to hand, a long route until reaching Autistic Man, then me. It’s an old issue, from years back.

“Let’s go, colonel,” I look up and observe him. “The moment has passed already.”

“No, no… I can do it… now I can,” and he keeps masturbating without a method and without pause, unable to achieve a decent erection. “She’s gonna know that I can fuck her like anyone else,” and with his trembling hand he presses his elusive glans against the dead lips of Vida’s vagina, trying to make way. “I have her heart but I’m still… I’m still me, right?” He looks at me, at us. “Isn’t that right?”

The colonel breathes with difficulty. Suddenly he stops touching his loins and pounds his chest forcefully. His face covered in sweat is paralyzed in a grimace. A scream of pain is cut short in his throat. It’s just a few seconds before he falls on top of her like a dead animal.

I go up to him. I look for a pulse in his neck.

“A heart attack, or something like that,” I conclude.

Acrylic on Canvas, by Luis Trápaga

We push the corpses into the pit. Then we hear that noise that comes from afar and approaches, approaches, approaches more and more. Preceded by a noise of interference, the electronic mist reaches us again: The great screen looms over us and goes through us and keeps moving, leaving us with an altered shine and contrast. On mute. I’m about to start running.

“I think you should go watch the TV,” Autistic Man tells me.

I run to the checkpoint. The National Television Newscast isn’t over yet and gives no sign of ending any time soon.

The colonel speaks to the camera. The colonel is wearing discrete but efficient make-up, powder and eyelashes, his hair nicely set on his shoulders, real tits, fake earrings. The colonel is talking about a documentary that will soon be released; he reads with an affected voice the prodigious phrase of insular engineering.

I turn the volume up. The colonel, wearing a perfect smile, announces they are now in contact with Vida G, who at this moment is in…

I back away, stumble on a chair, leave. “Go ahead, Vida.”

I see her, microphone in hand, coming toward me. There are no cameras, or I can’t see them. Nor can I tell where so much light is coming from.

To my left, suspended in the air at the height of my arm, is the logo of the Newscast beside the luminous letters that say LIVE. She walks dragging her high heels, one of them twisted and the other absent. Her dress and her arms are covered with coagulated dirt. Her eyes are two opaque crystal beads. She is transporting cockroaches and flies in her hair. Her entire body gives the impression of being full of holes through which things enter and exit.

Of course, I already know what she will ask me:

“Do you have anything to say about the construction of the freeway?”

Vida G puts the microphone in my face. I observe her bony hands, the nails that keep growing, unpainted and broken. The perfume becomes intense.

“Nothing else,” I answer.

But I could just as well add any other phrase. Besides, no one is going to understand what I’m trying to say.

Edited in English by Joshua Barnes

__________

All facts and characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Los hechos y/o personajes de esta historia son ficticios, cualquier semejanza con la realidad es pura coincidencia.