No Borders: An Interview with Eduardo Halfon

by Joshua Barnes / December 10, 2012 / 1 Comment

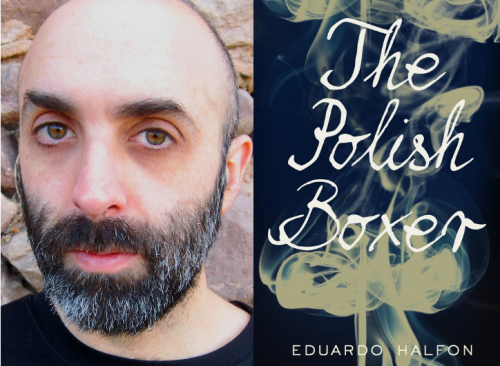

Eduardo Halfon and his first novel to be translated into English, The Polish Boxer. Photo courtesy of the writer.

Born in Guatemala in 1971, Eduardo Halfon came to the United States when he was ten years old. He studied Industrial Engineering at North Carolina State University and moved back to Guatemala in his early twenties, taking a job in that field. But the difficulties of working a job that he says, “wasn’t really me,” in a country that was no longer his own, while speaking Spanish—a language that he had “basically forgotten”—left him frustrated. In the process of searching for answers, when he was in his late twenties Halfon took a course in literature at a local university and became avidly, irrevocably interested in reading. As a side effect of his newfound bibliophilia, Halfon eventually started writing.

Now, at the age of 41, his literary career is in bloom. Aside from being recognized in 2007 by the Hay Festival of Bogotá, Colombia, as one of the best young Latin American writers, Halfon has published ten works of fiction in Spanish. They include: La pirueta (2010), winner of the José María de Pereda Prize for Short Novel, El ángel literario (2004), an attempt to trace the literary origins of writers, and El boxeador polaco (2008), which was published in English this year by Bellvue Literary Press in the U.S. and Pushkin Press in the U.K., as The Polish Boxer.

The Polish Boxer is voiced by a narrator (also named Eduardo Halfon) who tells fragmented stories about searching for things—a missing student, the truth about his grandfather’s tattoo from Auschwitz, a mysterious Roma pianist named Milan—in a narrative that travels from a university in Guatemala to a literary conference in North Carolina to the streets of snowy Belgrade. Populated by people both real and imagined, the book flashes by like a disquieting dream. Tonally, much of this ten chapter work is elusive, autobiographical, and resists categorization.

When Halfon and I first talked via Skype in October he had just returned to Nebraska, where he currently lives, from a ten-day book tour of London and New York for The Polish Boxer. After he took another trip to New York with one of his translators, we spoke again in December, just as he was finishing up a new manuscript.

In this interview, Halfon, a man who always seems to be jumping across borders, discusses the characters in his last publication, the music in his writing, his feelings of nomadism, and why he is reluctant to distinguish himself from his eponymous narrator.

Lets talk about The Polish Boxer and its personal consequences. In the chapter “A Speech at Póvoa” you write about how difficult it was to find a way to properly tell your grandfather’s story of survival in Auschwitz. Can you talk about how that journey played out for you?

If you go back to a book I published in 2004 called El ángel literario (The Literary Angel), there’s a scene where I explain to the Spanish writer Andrés Trapiello that I’m carrying my grandfather’s story under my arm, but that I don’t want to tell it. That was four years before The Polish Boxer came out in Spanish. So I lugged this story around for a long time, afraid to tell it, unwilling to tell it, not knowing how to tell it. Still, it would come out everywhere because it was an intimate part of my family and my life.

That story is the centerpiece of the book. The Polish boxer himself—the character—is a figure that is barely present, or not present at all. Yet he is. He’s like a specter, or like a breath that permeates the book. Something that you can’t point to, that you can’t really see, but that you can feel. And that’s what my grandfather’s story was to me. It was this huge story that was barely present.

- Eduardo Halfon reads from The Polish Boxer

- Eduardo Halfon reads an excerpt about his grandfather from The Polish Boxer at Pacific Northwest College.

In the book Halfon says his grandfather always told him that the tattoo was his phone number. So, it’s emotionally intense when he finally explains that it was a mark of his time in Auschwitz. You have said in other interviews that this is actually autobiographical. Was it freeing to finally write this book?

It wasn’t an emotional trip for me. None of my books are. For me, they are not releases, or ways of coming to terms with things, or of understanding the world, or of feeling better about a situation. I never feel better after writing a book. I never feel as though I’ve come to understand something. I just keep writing. And writing, for me, is never an ending. I don’t arrive. I keep going. I have to keep going.

Was your grandfather able to read the book while he was alive?

The book was published in Spain in 2008, and he died in 2010. My mother said she read it to him, and he cried the entire time. I don’t know how much he understood—he was elderly and very ill, almost senile towards the end. Perhaps he cried because he knew that his story would survive him. Or at least that’s what I like to think. In the last chapter of The Polish Boxer I write his deathbed scene. An interesting side note to this, which I decided to leave out of the story, is that when I went to his room on the morning that he died, there, sitting on his nightstand, was a copy of El boxeador polaco.

Now I would like to know more about Halfon, the writer. Were you always this rational about your emotions?

I never cry. I’ve cried two times in the past twenty years, and both times have been over cats. Yet I feel like crying all the time. I appear to be a very rational, methodical person, but that is really a façade, isn’t it? There is this duality in me between the irrational and the rational, between the emotional and the structured. Maybe that is the reason why I felt so safe when I played music, as a child and teenager, because in music you can be both, you have to be both. And in my type of writing, I have to be both, as well.

There are many dualities in your life. It’s really difficult, for example, to assign you just one identity or set of roots. Do you ever consider yourself a citizen of a particular country?

Not at all. It’s a constant feeling of being outside, of wanting to be outside. It’s not a choice. I’ve just never felt that I belonged anywhere—not in Guatemala, not in the United States, not in Spain. I don’t know why that is, but it’s my reality. It’s a very fluid existence. I can pretend to be where I’m at: I’m very American if I’m in the U.S., and I’m very Guatemalan if I’m in Guatemala, and I’m very Spanish in Spain. I can modify my voice and my physical appearance and pretend to be from where I’m living at the moment. Yet I’m not really there.

Before you became a writer, you were an engineer. Does that methodical occupation affect your work?

I was an engineer way before I studied engineering. I am very systematical, very organized, very methodical, almost to neurosis. When I write I am very much an engineer of language, and also an engineer of the story itself—the structure, the characters, the order in which to tell it.

But my writing is also spontaneous. When I start I don’t know if I’m writing a page, or a hundred pages, or nothing at all. But it’s not that I do some sort of Dadaist, freeform writing and then the other part comes and corrects it. No. The tricky bit is for these two sides of me to get along, to know when it’s time for the spontaneous, free part of writing, and when it’s time for the structural part of writing. It’s like learning a new dance.

Lets talk about your spontaneous/methodical writing. Something that also stands out is your ability to interrupt a story to pursue an unexpected tangent without being disperse.

Those interruptions can’t be gratuitous, though. There has to be something there that takes you somewhere as a reader. In the story “The Polish Boxer,” for example, at the height of my grandfather’s narrative, I suddenly break into a childhood scene where I ask my mother where babies come from. As I was writing that scene, I myself was confused. Why was I doing it? I knew that that wasn’t the way a story is supposed to be written. But I also knew, or felt, that it was right. Later, I understood why that flashback, at that moment, made the scene work. Of course, that’s not the way you write a story, according to those who know. But I don’t care about them. I just care about the story.

Is that also a strategy to maintain your reader’s attention?

The feeling of the rug being pulled out from under you is important in my writing in general, and particularly in The Polish Boxer. At some point you shouldn’t know what to expect anymore, and that’s exactly what I want. You don’t know if what you’ve read is an ending or a beginning, if in the next page I’m going to contradict what I just told you. For me, it’s important to keep the reader on guard, always a little uncomfortable. That element of slight discomfort is very important in short story writing, and in my writing in particular.

I appreciate that you say that. For me, as a reader, a constant discomfort was trying to understand the difference between Halfon, the character of The Polish Boxer, and Halfon the writer. How do you draw a line between those two entities?

I don’t. Part of the intention is lulling the reader into thinking that both Halfons are the same person, that what they’re reading is absolutely real, and not fiction. In doing so, I want to create an emotional response, similar to what a musician would do through music.

It’s impossible to talk about your creative process and leave out music. How does music influence your writing? (Click here for a soundtrack to Eduardo Halfon’s texts.)

I’m always going back to music. Music is the only art that needs no rational mediation—it either goes straight in or it doesn’t. There’s a strong lyrical component to what I write—in beats, repetitions, the words themselves—and that’s very tricky to achieve, and almost impossible to fix when it’s not there.

And in this process, how much do you value silence?

Silence is key. There’re two types of silence: the external, which is marked by interruptions or street noise; and the internal silence, the internal calmness that I need to write. For me, both of these are key.

Can you tell us something about your new novel?

It’s called Monastery, and takes place in Israel. It grows out of The Polish Boxer. It’s part of that same universe, part of those same stories and characters and preoccupations. As I was telling you earlier, there are no endings. I just keep writing.

One Comment on "No Borders: An Interview with Eduardo Halfon"

Trackbacks for this post