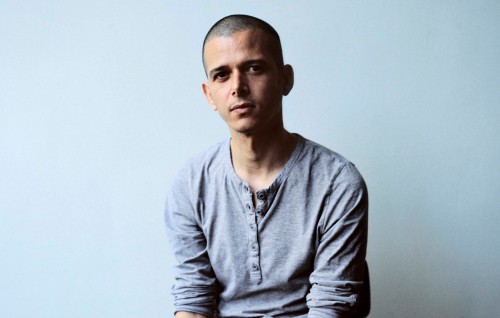

A conversation with Moroccan novelist Abdellah Taïa

by Joe Edgar / September 10, 2012 / 2 Comments

Moroccan novelist Abdellah Taïa was born in 1973 in Rabat. Reared in the town of Salé by working-class parents—his father worked as a janitor in a local library, exposing Taïa to books at an early age—the family stressed education and sent five of their nine children to university. Taïa elected to study French Literature at the University of Rabat, his gaze set upon Paris and the possibilities that city represented to him, namely a career in film. Eventually he landed at the Sorbonne.

In Paris Taïa broke away from what he saw as the oppressive confines of his family and Moroccan society and began a process of self-actualization. At the start of his literary career, Taïa publicly declared his homosexuality in the magazine TelQuel. This created a scandal in Morocco and opened up a debate about gay rights and the repression of the individual in Morocco, and to a greater extent, the entire Arab world. That was in 2006. To this day he is the only Moroccan intellectual to “come out” publicly. Now a seasoned Parisian ex-pat, Taïa exists between worlds.

Five of Taïa’s novels, fictional accounts of his experiences, have been published by French Editions du Seuil. Two of his books, L’armée du Salut (Salvation Army) (2009) and Une Mélancolie Arabe (An Arab Melancholia) (2012) were translated into English by Semiotext(e). His novel Le Jour du Roi was awarded the prestigious French Prix de Flore in 2010.

Sampsonia Way caught up with Taïa via Skype on the eve of the release of his latest novel Infidels, due out in late August. In this interview he offers his thoughts on the society he grew up, his writing process, and the realization of his childhood dreams.

Why did you leave Morocco? Are you in self-imposed exile in France?

In order to become an adult every person has to leave his home town and go to another city, or another country. When I was thirteen, I decided that one day I would go to Paris in order to be what I wanted to be: A director and filmmaker.

Do you think setting out on one’s own is especially important for those of us who are homosexual and have experienced alienation in the culture that we grew up in?

No, I don’t think alienation is a specific thing to homosexuals. Heterosexuals are also alienated. The problem with homosexuals is that they are not accepted from the beginning. Where I come from, homosexuals allegedly do not exist, which is a horrible thing to live with and to accept. I had no other choice but to accept this non-existence. We could call this exile, meaning that your people, the ones who say they love you, that want to protect you, that want the best for you, and give you food—milk, honey, and so many other things—they deny you the most important thing, which is recognizing you as a human being.

In 2006 you were the first Moroccan intellectual to “come out of the closet” publicly. Why did you do it?

I never hide. I never put that aspect of my personality aside. I know so many gay intellectuals or writers who say, “I am not going to talk about homosexuality because it doesn’t interest people.” But for me this makes no sense. It would be like a heterosexual who doesn’t present himself as a heterosexual. I never planned to come out.

When my second book, Le rouge du Tarbouche, came out in Morocco, I was interviewed by a journalist from the magazine Telquel. She wanted to do a profile on me and was interested in speaking about the themes of homosexuality in my books. She wanted to know if I was willing to speak freely. We were in a coffee shop in Casablanca. I never imagined it would happen like that, but I understood that was the moment of truth: The truth about me, my books, and my position in the world. Although it was really scary and I knew that there would be many consequences, I had to do it. I owed it to that little boy who had dreams at thirteen. Now that I have the possibility to speak, I’m not going to stop.

I read that after that article was published, you barricaded yourself in your hotel room. Has it been dangerous for you?

I am in no physical danger… However, the mechanism of fear is still inside of me. When you finally say something, it materializes. When that article appeared, it was the first time that I assumed responsibility for everything. We have this desire to be what we want to be as individuals, which can come into conflict with our political identities—what we are and what we should and should not do. The realization of this and the process of undoing it takes many years.

The story became a big sensation in Morocco. Two things: Some of the Moroccan press was really supportive. The French press and some of the Arabic press were too, I must admit. Others were just attacking, attacking, attacking without stop.

Now that I have the possibility to speak, I’m not going to stop.

Has the climate for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) community in Morocco changed since you “came out”?

It’s still a crime punishable by a prison sentence. What did change is that now, when officials talk about human rights and the freedom of individuals, they also talk about homosexuals. “Mithly” is a word that has been invented in Arabic to refer to homosexuals without insulting them. It has become a huge thing in the Arab world. Mithly means “like me” or “the one like me.”

Has your writing been banned in any part of the Arab world?

My novel Le jour de Roi about King Hassan II was banned in Morocco. It’s a novel about how Hassan II changed everything in the minds of the Moroccan people, about his dictatorship, and the social war between classes in Morocco. It’s a story of the friendship and love between Omar and Khalid, a rich boy and a poor boy. When it received the 2010 Prix de Flore literary prize in France, the ban was lifted. My books are now translated into Arabic and are available in Morocco, a sign that things are changing.

Your books have also been translated into seven other languages. What is that process like for you? Do you participate in the translation or have a relationship with the translator?

No, I don’t. I just let them do it. If they have questions for me, I answer. I can speak English, but I don’t have great control of the language. I just trust the editor and the translator. When my last book was translated into Arabic, I worked with the translator because she asked me to. Having my work translated is a surprise to me—I don’t know how it happened. My French publishing house (Editions Séguier) does a good job.

You know, the process of writing is a very passionate experience. But when the book is printed, I have no interest in it. I cannot read it, I cannot add anything else. I don’t want to be involved. Sometimes when I read something I’ve written I think, “Oh God, how did I accept to have this published?” That is my first reaction: I want to change everything.

Was it a political choice to write in French instead of Arabic, your first language?

You have to find your fault in language, even when you speak and write in your mother tongue. To find a literary style, language has to become something strange. The French language is doubly strange for me.

As I told you earlier, I had decided to go to Paris when I was thirteen, but I didn’t realize what that meant. All I knew was that Paris was like a big signal in my life. In order to realize my dream, I had to master French. So I went to study French literature in the University of Rabat. However, when I arrived, I realized that my French was really poor. To master it, I decided to write my diary in French. For me that was the best way to be confronted with the language, to have a relationship with it without any mediation or intercession. My literary writing emerged from this relationship and that diary, which I kept for many years in Morocco. That’s how I became a writer.

Do you continue to keep a diary?

I don’t write diaries anymore. I have notebooks where I put images, my thoughts, my ideas, and my crazy projects. I can write anywhere but my favorite place to write is in bed. I like to spend a lot of time in bed alone – thinking about things, watching movies, reading, and writing. I’ve written over half of my work in bed, I think. I hope that everyone is now over the cliché that to stay in bed is a lazy thing.

Because of your notoriety, you’ve become a go-to commentator on gay rights, the Arab Spring, and revolutions in the Middle East. Did this role come naturally to you?

My life now is part of a process I started many years ago. To be able to begin my life I had to cut myself off from my family, even though I was still among them. I started to speak to the world in my head. Today the writing, commentary, and even speaking to you right now is a continuation of that.

As a Moroccan, an Arab, a Muslim, an African, and a writer I know that when you have the opportunity to speak you have to do it. There is no other choice. I am also very happy to speak about things that other people say don’t exist. They say homosexuality doesn’t exist in the Arab world, but I am here to prove the opposite and speak about it from the interior. I have to speak about it to give the correct image and be forthright about individuality in the modern Arab and African worlds. The problem with the governments that run the Arab world is that they don’t allow people to start the process of their individual evolution. Hopefully with the Arab Spring that will really start. I believe that the Arab Spring is bringing something free and historically new for all of us. I do hope so. Otherwise my speech, my words, my ability to be involved with the movement, and write articles about the Arab revolution will have had no meaning.

Also, aside from their intellectual importance, I believe that books help us to live. When you read a book or a poem it connects you to something new inside of you or it confirms some premonition you’ve had. Using my books as a cultural instrument in the fight for freedom, for individuality, is something I’m very happy to do. Since I come from a world where individuality doesn’t exist, where homosexuality is still considered a crime, where you don’t completely own your body, and where you can’t speak freely, it’s the least I can do. The past ten years in Morocco have brought some change, but politically, socially, and traditionally the individual cannot be as free as they want. They are not protected by the law.

“As a Moroccan, an Arab, a Muslim, an African, and a writer I know that when you have the opportunity to speak you have to do it, there is no other choice.”

What have been some of the challenges that come with being a public figure?

To say something with meaning, with heart. To give something. I try not to play the role of an intellectual living outside the world but connected to the world. I don’t know if I succeed in that.

Is your writing process a catharsis?

It is not a catharsis at all. To write, to construct, is to be connected to something else. In writing you reach other voices inside of you, your faith. Not faith in a religious sense, but in the sense that as human beings we are constructed from the ashes of the stars. Everything on Earth began in the stars. It seems like it can’t be true, but it is. And I believe that when I write, it is a connection to light, to the stars, to energy. I don’t want to sound like a guru, but when you write it is not totally about you.

You have written some very personal things.

Those are the lines that I have…

They are the confines that you operate within?

Yes, I have nothing else. If I could be a writer without words I would do that, but human beings didn’t invent anything other than language to write and speak with. My life—what I have in my head, in my eyes, in my skin, my blood, and my sex—is all that I can give. I change it into literature, which is kind of a mystical vision of writing.

You wrote an op-ed piece in the New York Times stating that you had to metaphorically kill your child self—the innocent, effeminate, and naive little boy—in order to remain safe in a repressive community. Have you been able to reconcile your adult self and your childhood self since then?

No, not yet at all. Everything has become much more complicated since my mother’s death two years ago. I thought the intelligent aspect of me would keep me safe and I protected the child that I was by being intelligent in society. During that process I killed other things in me. After my mother died, all of those problems from when I was a child came back and I realized how alone I was in the world. Suddenly, to be gay became as heavy as it was when I was little. I had convinced myself that the humiliation, the insults, and the killing of a side of myself were not important, but now that’s all coming back. Although I live in Paris and there are many good psychoanalysts, I don’t believe in that yet.

What parts of your earlier self were you able to preserve?

The determination; I don’t change my mind easily, I never give up.

“The problem with the governments that run the Arab world is that they don’t allow people to start the process of their individual evolution.”

I noticed that one of the themes in your work is unrequited love, presented in the protagonist’s perpetual search for love, his constant longing for something…

I do believe in fairy tales. When I was little I used to watch Egyptian movies where suddenly the girl finds the boy and they marry. I always believed that at some point I would have that too. I sincerely believed that I would find a man and we would go to the mosque and be married. It’s similar to the desire I have to be a filmmaker. I will never give up on that dream and I will never stop believing in some fairy tales. C’est contradictoire, non?

Would you categorize your work as memoir or fiction?

I don’t believe that my work is autobiographical or memoir, though it has been described like that. I write novels, texts. They are not expressions of my social self, they are expressions of something else. I don’t know what label we should put on them. Though the experiences and scenes are coming from my life, when I start to write there are so many things that come out and put themselves into the text. I have no idea about those things five minutes before I start writing. The fictionalized always comes out and puts itself into my writing. But I don’t agree with the definition of fiction. Is it something that has nothing to do with us, that is made up? I don’t believe in that. As human beings, in order to make our lives acceptable and not too sad, we imagine things. We do it all the time. How would you label that? Fiction? Not for me. What I invent, what I imagine, is part of something.

It’s drawing from your own truth, your own experience?

Voila! To write “fiction” is to write something that has nothing to do with you. How could we possibly do that?

What has become of your dream to work in film?

I am still pursuing it, as a director and screenwriter. There’s a specific project but I can’t talk about it now.

Will you ever live in Morocco again?

I have no idea. I turned thirty-nine yesterday [August 8] and I feel like I am just at the beginning of something. That beginning is happening for me in Paris, not in Morocco. It’s not that I hate Morocco but I still have a lot of psychological problems with the country and my family that I haven’t resolved. Still, I return to Morocco often, up to six times a year. When I go, there is something overly emotional that prevents me from being myself. It seems like I don’t exist there yet, although I am trying to prove the opposite. For so many people in Morocco and in my family, I don’t exist. We practice the same non-existence on each other. In my family we keep it “civilized.” We don’t talk about the important things.

2 Comments on "A conversation with Moroccan novelist Abdellah Taïa"

Beautifully done! I could feel that this interview open a path for me, to touch Abdellah Taïa hearth, for a moment I felt that he was part of me and I was part of him.

This interview makes my heart was touched

To the extent that this does not feel the eyes shed tears.

That’s wonderful

Best wishes always to Abdellah Taïa