Chinese writer Yu Kwang-chung: “Poetry can be used for many purposes, one of which is as a weapon.”

by Clare Gates / August 29, 2011 / No comments

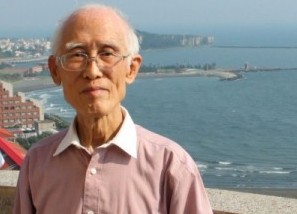

I met Yu Kwang-chung (余光中), one of the Chinese-speaking world’s best-known and best-loved poets, authors and translators, near Mount Chai in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, not far from a palm tree-lined seashore. The serene gentleman, who sported leather shoes, slacks, and a long-sleeved dress shirt despite the scorching heat, welcomed me into his office, which was overflowing with Chinese and English books. We were at Sun Yat-Sen University where the poet, now Professor Emeritus, was once Dean of the College of the Liberal Arts. Yu was born in Nanjing, China, in 1928, but he and his family fled to Taiwan via Hong Kong in 1950 after the Kuomintang, Taiwan’s oldest and current ruling party, was defeated during the Chinese Civil War. His poetry critiques Communist China’s destruction of free speech and culture but also the Kuomintang’s “White Terror,” Taiwan’s 38-year period of martial law (1949-1987).

Yu is currently the author of 50 books, 18 in verse, the rest in criticism, prose, and translation. He has earned praise for his versatile, lyrical essays, and The Columbia Anthology of Modern Chinese Literature has called him “one of the most prolific and acclaimed writers in Taiwan.” Yu has also received honorary doctorates and won half a dozen major literary awards in Taiwan and China including the National Literary Award in Poetry and the Wu San-lian Literary Award in Prose.

Yu, who has traveled widely, has taught in Hong Kong, studied in the United States where he was a Fulbright visiting professor twice, and frequently visits China. While his past work is nostalgic for mainland China, Yu has chosen to make his permanent home in voluntary exile in Taiwan.

In this interview Yu Kwang-chung talks about the tradition of Chinese literature, immortality, the joys and complications of sourcing multiple languages, and the contradiction of being known as a “patriotic” poet in China.

In your essay “Translation and Creative Writing” you said that you wanted to avoid “translationese,” or sounding translated. What else makes a successful translation in your opinion?

In that case, a good translator must have full mastery of the target language and must have full understanding of the source language. So my work in translation is more from English into Chinese than vice versa because, of course, I have a better mastery of Chinese.

What themes do you consider particularly Chinese in The Night Watchman? I know that one of the reasons your poems are famous is because they have a wistfulness for mainland China, particularly “Nostalgia.” Do you consider nostalgia a particularly Chinese theme?

The theme of nostalgia, like the more general theme of diaspora, has come down a long way in literary history. It’s in the human nature to miss one’s home, even only two hundred miles away. Even our students here on campus miss their homes in the north of the island. Not to mention that China is such a big country, and there have been so many wars. Officials were often demoted and put in exile and things like that. There are many occasions for one to miss home. I think that’s universal. You must be acquainted with Robert Browning’s poem “Home Thoughts From Abroad”: “Oh to be in England / now that April’s there.” This is of course sometimes not the case with the young romantics. For instance, Shelley and Byron, they hated their home! They were rebels! They felt quite at home in Europe rather than back in England. But as a rule this theme of nostalgia is quite universal.

Many of your poems address the themes of time and immortality. What do you think is the relationship between the poet and immortality? On one hand, you say in the forward to The Night Watchman that “To remain a poet is to remain young, which gives one the illusion of immortality.” But then in “Green Bristlegrass” you write: “None ends up taller than the bristle grass unless his name soars to the stars.”

Of course our physical lives are quite limited. Religion is helpful to let one imagine that there is a future life after this corporeal existence. But literature as well as the arts can give us some consolation that we may be immortal because our works will survive us. This is evident in Shakespeare’s sonnets. One naturally tends to think that his works are immortal, eternal. But one cannot be sure. You see, so many artists and poets have died young. Van Gogh wasn’t so sure of himself. When he died, he was thirty-seven and he had only sold one piece of his oil paintings. And so the same happened with Raphael, Mozart, and so many of them. But one of our major poets in classic China, Du Fu, was quite sure of himself. He has two lines: writing is for eternity. One knows it oneself in the few inches of the heart. That is intuition. But one can be mistakenly self-sure in such matters. Thousands of artists struggled in Paris, and even do now. Only a few of them became Picasso and Matisse.

“The White Jade Bitter Gourd” and “The Emerald White Cabbage” are examples of your ekphrastic poetry. What is the purpose of your poetry in this genre?

This is quite an important genre in Chinese classical poetry. A poem is descriptive, expressive of artifacts like those in the Palace Museum, or of natural things like butterflies, swans, or trees—that is, things that are not human. Behind the description of things, your understanding of the thing can be something more than merely physical; often such poems involve metaphor. Robert Frost says, “A poem begins in delight and ends in wisdom.” We begin such descriptive poems in delight. I can spend a few lines on how beautiful, how attractive a thing is, and then come to something like an implied conclusion. I may compare the object to something else, something spiritual, and thus end in wisdom as Robert Frost says.

In your ekphrastic poem “the Sunflowers” you mix English and Chinese together. Why?

That isn’t my usual practice, but I think it is eligible in such a case because I am making use of montage. And I imagine there is actually an auctioneer: “Going, going gone.” I can’t translate it into Chinese—it would sound foolish. It must be in such words: going, going, gone. And so while I was in the United Kingdom, I often read my works to an audience. I included this one in my selections many times, and the response was quite immediate and very warm. The scene in this poem is international. It is not national.

You said in New Chinese Poetry in 1960: “The problem still remains to be solved whether traditional Chinese poetry or Western poetry should be the guiding influence [for new Chinese poetry], or whether they should be harmonized into dual inspiration.” How do you think things have turned out today? Do you think this problem still remains?

Now for poets like myself, English literature is a lifelong study. English literature has exerted a very great influence on my writings. At the same time, I am very much at home in Chinese, mostly classical Chinese. But I would think that I’ve been under the influence of three traditions: one is the tradition of classic Chinese language as well as the Chinese literary canon. The second is English and American literature. The third, the least influential, is the New Tradition of Chinese literature, beginning from the May 4th Movement, almost a hundred years ago.

One of your criticisms of ancient Chinese poetry is that it has “a narrow thematic scope” and should look to Western poetry to expand its horizons. How have you taken your own advice?

Well, the attitudes towards life are quite different. In Chinese literature we are not obsessed with the idea of sin like Christian writers. Also, our sense of immortality is different from the Christian sense in that our immortality involves the succession of the second generation from the first, the grandchildren from the children and so on. The Christian sense of immortality is a relationship between oneself and God, but our sense of immortality is more collective in the passage from generation to generation.

How do you see poetry’s, and the poet’s, role in political resistance? Does society still need a poet who will serve as a cultural guardian, or protector of arts?

In my poem, “The Night Watchman,” which I wrote during the Cultural Revolution, I compare poetry to my last resource. Of course, poetry can be used for many purposes, one of which is as a weapon. Since a writer is aspiring for immortality, poetry can also be a defense against mortality. The communists, especially during the Cultural Revolution, were quite destructive of traditional Chinese culture. As a defender of such, I wield my weapon against them. For many years I was attacked by the leftists as anti-revolutionary or something like that, but in recent years, the tables have turned. The press there, the media in mainland China, has been calling me a patriotic poet for quite a few years. This is quite ironic. Of course, Chinese communism has changed a lot. Not to our expectations, but it isn’t so harsh on the intellectuals anymore.

So you don’t think that China oppresses intellectuals so much anymore, but what about those who are in prison?

If you don’t speak out in the newspaper or over the T.V., the Party can be more tolerant. I know the Chinese are quite critical of the party in private conversations, but during the Cultural Revolution even such was impossible.

I’ve noticed that 19 of your 68 poems in The Night Watchman mention wings or birds. Do these poems, such as “There was a Dead Bird” and “All that Have Wings,” address the freedom of artistic expression?

“All that Have Wings” was a direct response to the Cultural Revolution. The other one was against the KMT. Originally the second one was written in defense of Li Ao, but later I came to dislike him so much that I usually don’t tell others what the original meaning is about!

In “Music Percussive” you strongly lament both your separation from China and your quarrels with the country, which has been “deserted, betrayed, insulted, raped again and again.” What was the climate in which you wrote this poem?

At that time, the name China was actually directed at Taiwan. A very influential magazine was closed under the pressure of Kuomintang. I was against Kuomintang, but my father was a Kuomintang member, so my family background is KMT. In a broader sense, I disliked Kuomintang as I disliked my father. But then, compared to the Communist Party, I would say Kuomintang was much more lenient. As Hu Shi, the May 4th Movement leader once said, “In China, especially during the Cultural Revolution, one not only didn’t have the freedom to speak up, one also didn’t have the freedom to keep silent.” You had to keep praising Mao Zedong and the party.

You have described yourself as walking a tightrope, striking a balance between the Western prodigal son and the Eastern filial son. Is this what you see as the future of Taiwanese poetry?

The situation now is quite complicated. As far as language is concerned, a writer like myself is under three pressures: One is the global onslaught of English becoming the language of the global village, while behind me is the local language and dialect. And then my own upbringing, my own education, is in the vernacular Chinese language now spoken by millions of Chinese people. In Taiwan if you can’t or if you don’t speak the Taiwanese dialect, you will be represented as though you don’t love this island. But actually the so-called “Taiwanese” dialect is a derivative handed down by the early immigrants from southern Fujian Province just across the Taiwan Strait.

Do you consider yourself Chinese or Taiwanese?

At present, 70% of the young people here, the college students, consider themselves Taiwanese, and at the most, only 30% consider themselves Chinese.

So what about you?

My answer is always: This is beyond question. You can consider the situation as a system of smaller and bigger rings, like a tree trunk. The Taiwanese identity is a smaller ring that is surrounded by the comprehensive ring of China, the outermost ring behind the tree’s bark.