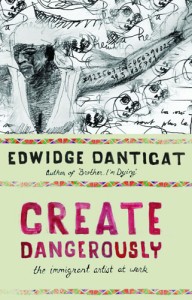

Edwidge Danticat on the Dangers of Being an Artist

by Elizabeth Hoover / February 1, 2011 / No comments

Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work, Edwidge Danticat’s recently published book of essays, begins with an execution. Danticat meticulously describes the death of Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin, two members of a guerilla army that tried—and failed—to overthrow François Duvalier, Haiti’s notoriously brutal dictator from 1957-1971.

Danticat, who left Haiti at age 12, calls this event her “creation myth”; it’s a story that obsesses her and compels her to write. For her the event, “involved a disobeyed directive from a higher authority and a brutal punishment as a result.” In Create Dangerously, she argues that the act of artistic creation can be as defiant as Numa and Drouin’s attempt to topple a dictator.

Throughout this book of essays, she examines tragedies both private and public—Hurricane Katrina, the September 11th terrorist attacks, losing her cousin in the Haitian earthquake—through the lens of literature. In clear, measured prose, she braids together incisive political commentary, personal reflection, and literary criticism.

Danticat published her first novel, Breath, Eyes, Memory, when she was 25-years-old and Oprah choose it for her book club. Since then she has published two collections of short stories and another novel, The Farming of Bones, for which she won an American Book Award. Her memoir Brother, I’m Dying, won a National Book Critics Circle Award. In 2009, she received a MacArthur “Genius” fellowship.

In this interview, conducted almost a year after the devastating earthquake in Haiti, Danticat speaks about the inspiring strength of Haitian women, how she handles the pressure of being asked to speak for a nation, and what it means to create dangerously.

The title of your book comes from an English translation of Albert Camus’ essay “The Artist and His Time.” What has the phrase “create dangerously” come to mean to you over the process of assembling the book?

There are people in this world this very minute who are creating dangerously; they are risking their lives for their art. That is the concrete meaning of “to create dangerously.” However, in a lot of other places, people are creating dangerously in a metaphorical sense. They are facing the basic fears that all artists have: failure, exposure, upsetting people with their words.

You took the risk of upsetting people in Breath, Eyes, Memory. In that book, the character Sophie is “tested” by her mother, meaning her mother examines her to make sure she is still a virgin. You were criticized for depicting this practice because, your critics argued, it makes Haiti look backwards.

When I’m in the writing process itself, it’s just me and the words. I never thought about representation issues when writing Breath, Eyes, Memory.

When you come out with your book, you expect resistance, but it’s always a shock when it comes from your own community. But it is a good shock because it keeps you from taking things for granted. Still, it shakes your notion of what you’re doing.

Breath, Eyes, Memory also shows the resilience and strength of a group of Haitian women. This is a theme that you return to in Create Dangerously. How have Haitian women and their stories become a source of inspiration for you?

I grew up with my mother, but she left when I was four. I had alternate mothers. They were strong women, but had little power in the larger community. They were poor and were not educated according to society’s definition, but they were brilliant to me. They had done so much with very little; they were my idols. Everything I write about Haitian women I model after one of my aunts, cousins, or grandmothers.

I draw from the lives of real women I’ve seen struggle, triumph, and do their best in spite of a society that has so many strikes against them because they’re poor, they’re women, they haven’t been to the same schools as others. It’s a very difficult society for women. And yet, there are a lot of female-headed households. The women are really amazing in Haiti.

The women I continue to meet here in Miami’s Little Haiti are in the same kind of circumstance, just in a different country: poor, but entrepreneurial.

What do you think is the origin of this hostility toward women?

I don’t think people realize they actively hate women, even as they work toward suppressing them. The amazing thing is that in Haiti, no matter what has been done to crush women, society hasn’t managed to do it. In spite of all the attempts at keeping women down, women survive. It would be romanticizing to say they thrive, but they keep holding up society.

The subtitle of Create Dangerously is “The Immigrant Artist at Work,” which situates the artist as a part of a wider community. How do you resolve the demands of being a member of a larger community while trying to maintain your singularity as an artist?

It’s a wonderful struggle to be engaged—personally and politically—in a community. But you have to withdraw. When you sit down to write, you have to shut down all other voices to do the work.

Personally, my biggest goal is to not be a distant observer to the Haitian community. I try to be a participatory observer. But when I have to work, I have to say to people, “I’m sorry but I have to work. You only know me because I do this work, so I have to continue it.” But they feed each other: the work I do in the community and the work I do alone at my desk.

In a sense, you identify as an individual artist and as a spokesperson for your community. Many of the authors I have interviewed for Sampsonia Way have rejected the notion that they should be seen as speaking for a larger community.

The writers who want to speak publically about their community and who want to speak for their community should be allowed to do so. There were two wonderful op-eds by Évelyne Trouillot in the New York Times about her life as a writer who lived in Haiti during the earthquake. I’m glad to see that voice come directly out of Haiti. If you want to know about the economy, you should talk to an economist, but there is also room for writers to talk about details of daily life, to talk about the nuance of certain things that perhaps the economist or the sociologist or the historian might miss. As observers of human nature, writers have something to contribute to the conversation.

How have you negotiated that in your own work?

I just speak up when I have something to say and I’m quiet when I don’t. That’s how I negotiate it.

It’s been a little over a year since the Haitian earthquake and one million people are still homeless. Has a sense of “compassion fatigue” set in?

In Haiti, we have these cycles of response: first there’s compassion, and then you have the “these people will never get their act together.” Often people neglect the fact that at different times, the Haitian people have quietly tried to get their act together, but things get placed in their way, things that don’t get in the news. We always ask people to pick themselves up at the worst times, when they are most unable to.

In my interview with the writer Sapphire, she spoke about how making education unaffordable to people of lower income levels is a form of censorship. Has cyclic poverty silenced Haitian voices?

It’s not just in Haiti but any place where people don’t have access to education, food or clean water. Every place where you have that, you aren’t just silencing people, you’re killing them and their ability to support themselves. Their ability to create a future for their children is taken away. If you’re not able to eat or have clean water your basic human rights are being violated.

In Create Dangerously, you look at moments of incredible tragedy like the earthquake, through the lens of literature, quoting from Ralph Ellison and Jean Genet. What does literature offer us in times of crisis?

A sense of perspective. A sense of comfort or even discomfort – the kind of discomfort that stirs us to act or that moves our heart and gives us a different window to look at something through. I wanted the book and the essays to be about how we read historical events, like the Haitian revolution or Michael Richards’ take on September 11th. I try to investigate how art fits into our daily lives, how we read, how we see, how we weave and sing. In Haiti, art is everywhere: the walls, the cars, the communes. It’s always with us. It’s our first response. I always wanted to bring it back to how people use art to cope, to survive.

And what does literature offer to you personally?

It has always offered me a great deal of comfort. You can always find the answer to everything in a book. Literature and art in general has always been extraordinarily comforting to me. It’s been my safe place, my harbor, and almost my true home.

Read the first chapter of Create Dangerously.

Read Edwidge Danticat Responds to Jean-Claude Duvalier’s Return to Haiti.

Read Elizabeth’s bio.