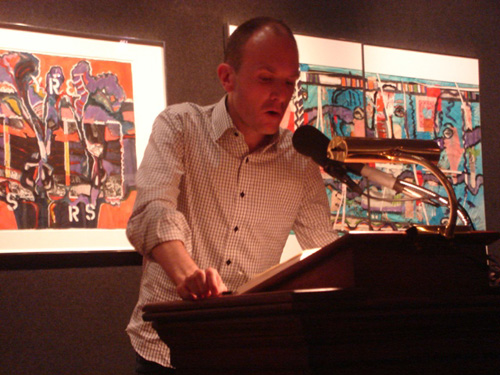

Lorin Stein: The Guardian of a Pantheon

by Silvia Duarte / October 25, 2010 / No comments

Photo © National Arts Club Page Series, pageseries.wordpress.com

New York, Washington, D.C., Pittsburgh, Chicago, San Francisco, Claremont, Los Angeles. Those were the cities in the whistle-stop tour of Lorin Stein. On his journey, the 37-year-old editor of The Paris Review hopped from train to train promoting a magazine that is 20 years older than him, a magazine that has become a map and a compass for universal literary opinion.

Stein has been described as “New York’s youngest, brightest, boldest literary powerbroker.” He was raised in Washington, D.C., attended the Sidwell Friends School, and graduated from Yale in 1995. Already an American critic and translator, Stein joined Farrar, Straus & Giroux at 25 and built a strong career as an editor.

Last April he replaced Philip Gourevitch–who ran the magazine for five years—and filled the shoes of George Plimpton –the first and legendary editor of The Paris Review. Since then, Stein started a series of revolutionary changes: the new daily blog updates the printed magazine’s content, the redesigned website has 200,000 visitors a month, and the magazine’s relationship with reportage has ended. However, the challenges he faces are steep. The new literary market doesn’t forgive anyone, and forgets almost everyone.

Striving to maintain a universal appeal is a difficult task to put on the shoulders of any editor. In taking over The Paris Review, Stein not only has to deal the magazine’s historically international readership, but also with criticism of the insular nature of United States’ literature. Insularity? Maybe. But Stein made an unusual point: he believes that the United States’ literary community also feels marginalized.

During his brief visit to Pittsburgh, Stein stopped by Sampsonia Way headquarters and took a break for this conversation. We talked about headaches, deadlines, writers, manuscripts, interviews, American awards, brothels and shit detectors. All his answers were infused with intelligence, precision and humour, just like the first issue of The Paris Review that he published.

After having edited books that received the National Book Award, or the Pulitzer Prize, you left Farrar, Straus & Giroux in March to join The Paris Review. What was your biggest fear at that point?

The thing that woke me up in the morning then is the same thing that wakes me up in the morning now: I’m interested in publishing and marketing fiction and poetry — and interviews and contemporary art— that I think should have a much bigger readership.

There is plenty of room for little magazines that don’t try to grow their readership and serve a very specific readership. That’s fine. That’s healthy. But the value of publishing a literary magazine is an open question. If you do it well, then the question is answered for the next month. But it is not a market that exists particularly, and I’m very interested in markets.

The recently redesigned website has 200,000 visitors a month

In a magazine, the deadlines are tighter and instead of dealing with the single ego of the writer you were editing, you now have to deal with many egos. What are your biggest headaches editing The Paris Review?

No headaches from the writers so far. I think the biggest headache is time: I still don’t know quite what’s going to be in our December issue. I have to learn how to relax and just trust in God…Well, probably not God, unfortunately!

A book can take about a year from the time you get the finished manuscript, so you have all the time in the world to figure out the jacket and all that stuff. A magazine is really different. And I don’t have sang-froid.

In a 2003 interview, George Plimpton said that The Paris Review got about 20,000 manuscripts a year. How many manuscripts have you gotten since you’ve started in April?

I don’t know because I don’t read them all. We have interns and editors who read them. But I spend every weekend, since I’ve started six months ago, reading submissions.

When I worked for a book publisher I wouldn’t keep reading if I saw the first page of a book and it wasn’t something I could imagine giving that much of my life to. Now I’m reading many good short things. There are many times when I ask someone on the staff for a second opinion, and this is new to me.

The Paris Review was founded as an alternative, as a vehicle for the voices of new writers. Is that still true today or does an unknown writer face the terrible phrase: “No unsolicited material accepted.”

No. No. We read it, almost definitely late—we’re still looking at things from March— but we read it. In the fall’s issue is a piece by John Daniels about Brazilian jiu-jitsu. I’d been reading him in N+1, a magazine that I admire at lot. He wrote an essay about hating Kafka and I loved it, so I sent it to all these different magazines, but they wouldn’t publish it, even though it was a good essay. It just wasn’t what they put out. That was the first moment that I thought I might want to, someday, start a book review.

Why was a book review your first thought?

Because I think that book reviews are a great American cultural treasure. And also there’s a tradition of the essay—the belletristic essay—that, in America, we take so much for granted that we don’t even talk about it, but we all read them all the time, and it’s not even considered high art. But if you look at a men’s magazine like GQ, most of them keep on staff at any given time a really serious essayist. I think that’s part of our patrimony…