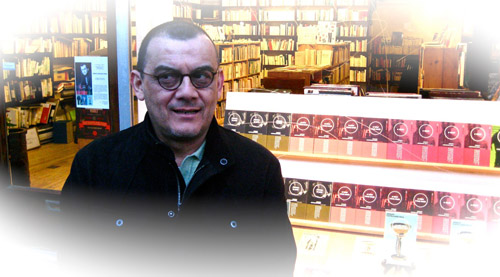

An Interview with Horacio Castellanos Moya

by Joshua Barnes / September 6, 2010 / 1 Comment

“If You Have Some Kind Of Sensibility Towards Injustice, You Know What Rage Is.”

Horacio Castellanos Moya was born in Honduras and raised in El Salvador. Throughout his career as a journalist and author, he has lived in Canada, Mexico, Guatemala, Germany and Japan, among others. In 2006 he came to Pittsburgh as an exiled writer-in-residence for City of Asylum/Pittsburgh, and he has lived here since.

Castellanos Moya’s writing is characterized by his fluid sentences and acerbic wit, a feature that occasionally gets him in trouble—not that he necessarily minds—but also endears him to fans of his honesty and force.

I sat down with Horacio in his home shortly after he completed his latest novel to talk about El Salvador, his three novels now translated into English, cultural tendencies, and his concept of success as a writer.

You just got back from El Salvador, a country whose political powers at one time threatened to kill you (after the publishing of El Asco). There’s a new, liberal government that’s in charge now, but what were the circumstances for your return?

I was invited for a conference and a reading. One was a kind of public conversation with another writer organized by the cultural office of the Spanish Embassy. The other event was in the Mexican embassy; it was a reading of my last novel. It is curious that in order to go to my own country I have to be invited by the Spanish and the Mexican embassies, not by any Salvadorian institution. Although I must mention that everything was arranged by a good friend, the poet Miguel Huezo Mixco.

There is a new government, as you said, the first leftist government in the whole of Salvadorian history. That means a lot. But it has been there just a year, so it’s quite soon to know the new changes. I guess it is moving on little by little. We’ll see.

Staying in the vein of revisiting the past: Dance With Snakes was first published in Spanish 14 years ago. It was just released by Biblioasis in the United States, translated into English by Lee Paula Springer. This means you had to re-read your own text to approve the translation. What was your reaction to reading something that was so old to you?

Well, that book is a weird book for me. Weird in the sense that it has all these fantastic elements that are not in my other books—snakes that speak, snakes that do things. So I have a special relationship with that novel because I don’t understand very well why and how I did it. I didn’t do too much planning. I just sat down and wrote the book in two, almost three weeks, and that’s the novel that you read.

I was not so concerned about what was going to happen with the book; I finished it and carried it around for a year before giving it to anyone. Then I gave it to a publisher in El Salvador and it was published. When I read it again for its publication in English, I didn’t discover anything new; I just confirmed that that book was weird. [Laughs]

Now I have a kind of very precise narrative universe that I am working on, and the character of Dance with Snakes and his environment are not inside this. It’s just that book is by itself, in its own bubble.

Indeed, Dance With Snakes’ reckless pace and deadpan narrator have been described as being akin to some hyper-violent cartoon. Your other books also create comedy out of tension: Senselessness weaves together panic attacks and seemingly mundane events, and The She-Devil In the Mirror conveys its unrest through trite, commercial absurdities. Do you see humor as a device that you use to help cope with social problems?

In the background of all my books is a way of laughing. We are a little bit like that in my country. I think that’s because El Salvador is so small and such a criminal country and our history has been so tragic that the only way of surviving, of getting along, is just laughing. There you cannot take life seriously because life is worth nothing. It’s very easy to get killed and it’s very difficult to survive. So I guess that’s a cultural point. And there are, in Salvadorian literature, many writers that have the same feature, more or less—this way of laughing all the time.

It’s like, if you are in the street and there is a corpse that has been shot, you are not going to go: “Ohh! He’s dead!” You say, “Fuck, what an ugly guy,” because he is not the first dead person you’ve seen.

Almost like the narrator in Senselessness, who is concerned with the poetic language of the manuscript he’s reading, instead of its horrific content.

Yeah. This guy in Senselessness is correcting this terrible manuscript [a testimony of the survivors of government-sponsored genocide] while he’s in the middle of this terrible society. He doesn’t try to be funny, but he is. It doesn’t depend on him. He’s concerned about so many petty details and stupid things, and he’s not so concerned about what he’s doing because he wants to escape. That’s a way of resisting. That’s a way of surviving: “I don’t want to get too much involved in this crap—there’s too much killing.” So in order to not be aware, not be so involved, he creates this distance between what he is doing and what he is thinking, and that is humorous. It’s hilarious in a way because this guy cannot match his mind and his reality. He is just trying to be separated from what he is doing.

But I don’t have any kind of explicit purpose or plan of being humorous in my books, it just happens that I belong to a culture where that is a natural way of being.

Which leads me to another question: The writing really speeds up when you get to spots of rage or paranoia. Your narrators get incredibly angry or scared and the language shifts into something close to stream of consciousness. Writing in that style expresses an immediacy and urgency of feeling, and I’m wondering if, while writing these texts, you feel the intense paranoia or rage your characters feel?

Well, paranoia is another way of being realistic in a violent society. If you go to a bar, what you are checking is to see who has a weapon. That’s the first thing that you check because you don’t want to be surprised. If you are on the corner waiting for the bus you are checking around. You don’t want to be robbed, or before, during the civil war, you didn’t know if there were some guerillas or military around and they were going to start shooting. So, you have to be aware. And it’s a way of being above all in El Salvador and Guatemala. There, it’s a long story about how violence affects you—and I’m not talking about just political violence; it could be political, it could be just criminal, it could be family violence, whatever.

As for rage, if you have some kind of sensibility towards injustice you know what rage is. For me, it’s not that difficult to feel rage. And sometimes I’ve been wondering if all my writing is related to rage, in the sense that rage is a kind of impulse that produces my writing. But now I’m not so sure. I don’t know, it could be one of the impulses.

It is very important for me though. Without rage, I don’t know if I would have written the books that I wrote. What for? I don’t write to entertain. If people get entertainment, that’s nice, but it’s not my objective. I just want to take out something that is inside me and is bothering me. I think that rage is one of the mechanisms that allows me to do that.

In a lot of your books—especially in Senselessness and Dance With Snakes—you have a protagonist who is running from something, only to find it again in the end. The plot always seems to follow them, wherever they go. I see a reflection of your own life in the structure of the books: You moved from the violence of El Salvador only to come back and write about the very place that you’ve left.

I have a book of short stories that is called something like The Fugitive’s Profile. And yeah, that’s a factor in my books. Characters are escaping. In my last novel, Tyrant Memory [to be published by New Directions in June of 2011], there are two characters who are escaping because if they are captured they are going to be killed for taking part in a coup against the dictator. Most of my books have this kind of character who is escaping. Of course, that’s related with my own life.

But, there are two levels of escaping: there is escaping from danger, from someone who wants to kill you, or you imagine wants to kill you—as Laura Rivera’s escaping of Robocop [in She-Devil in the Mirror]. But there is another level of escaping, and that is when you don’t want to be where you are, or you don’t want to be who you are, as is the case with the narrator in Dance With Snakes. It’s a way of escaping from yourself.

So how did you go about constructing the distinctly feminine voice for She-Devil in the Mirror?

That was my first experience of writing a female character in first person and it was not that difficult. I’ve been surrounded by these kinds of voices: my grandmother—who is dead—my mother and many lady friends in El Salvador. You put six of these women in a room and you wouldn’t know which is the character of my book. They just don’t stop talking.

I had been hearing this type of voice since I was a child. Once I got the timbre—the rhythm, I had it! It was an accumulation of features. Actually, the voice was not the challenge. The challenge was the character’s mentality—her attitude towards life, towards precise situations. So what I did was pay a lot of attention to my lady friends, just to check their mentalities and imagine how they would react. I mean, this mentality of having all of these affairs under the table and lying about this, and being related with that, and gossiping here…

She is constantly defining events and then contradicting herself, using some kind of coping phrase or excuse to cover up the inconsistency…

When you are taught to lie, your consciousness bothers you. So you lie to yourself. But there is one moment where you have to make an extra effort just to keep going; otherwise, you have a kind of breakdown—that’s what happens to her at the end. That novel is about lying. It is not about the killing. It is about a culture of lying. Lies, lies, lies, lies, all around.

In “Bolaño Inc,” which appeared in Guernica in 2009, you bemoan publishers’ marketing of Latin-American literature in the U.S and the mythologized image they assign to popular writers such as Roberto Bolaño. Did you see some of the responses you got when that was published?

Yes. Some people sent me emails. But all the anger of these people is normal. Bolaño is an idol, so people don’t read him as a writer. We live in very empty times, so you look for someone to fill your emptiness, and some people read fiction looking for truth, for a kind of salvation, which is why a writer like Paulo Coelho is so popular. And it’s funny, these attacks on that article, most of them came from Latin American residents in the USA, because those are the ones who feel much more vulnerable when you attack all this celebrity crap of American culture that they believe in. [Laughs] When the article was first published in the daily newspaper La Nación from Buenos Aires, the reactions were very positive.

You were called “jealous” and a “bigot,” and one incensed comment says that you should rot in your own jealousies for the rest of your life. But you’ve published nine novels and five short-story collections translated to many languages. Still, in comparison to Bolaño, in the eyes of the American market you’re relatively below-the-radar. The main difference, maybe, is that you are still alive. In this midst of all these factors and pressures, how do you evaluate and define success? What does success mean to you?

For me, success would be if I write the books that I should write. If I am able to write and finish the books that are inside me, even if I don’t publish them, that would be success. But let me tell you, success is a very American concept, although now it is everywhere. It’s not a word that defines my work. I do not assume it. That word is related to market, celebrity, fame, and money, and in my case, I became a writer in a place where those values were not related to literature, where to be a writer was nothing. There was no way of getting “success.” There was no way of getting money and celebrity because of writing books. What you could get was to be shot, or to be labeled a communist.

When I was first published, I already had other values; for me, literature was a way of being rebellious against the society where I was, and expressing the rage that that society created in me. Those were the values that I had when I started to write, and in a way some of them are still my values. That doesn’t mean that I don’t like to sell books or I don’t like fame—everybody likes that. But what I mean is that my main motivation to write is not related with that idea of success.

The funny thing is that success is a very American concept, but American literature was created by failure, not by success. I mean, the three founders of American literature as we know them were Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman. But those three were losers—American literature was founded by losers! Perhaps that is why there is now such an obsession with success…

Read an excerpt of Horacio Castellanos Moya’s Dance With Snakes.

Read Joshua’s bio.

One Comment on "An Interview with Horacio Castellanos Moya"

Trackbacks for this post