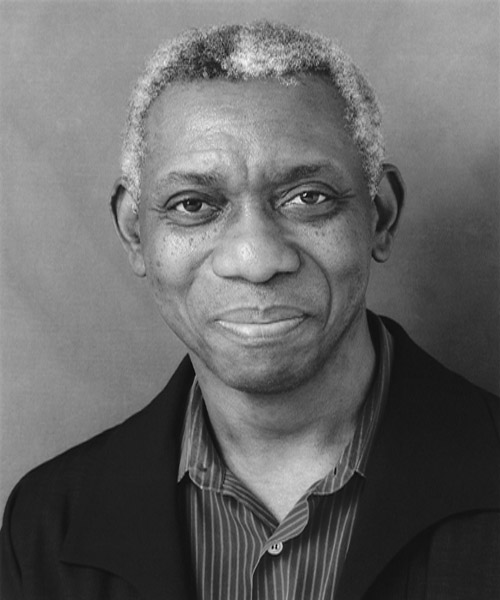

Songs of Rage and Tenderness: The Poetry of Yusef Komunyakaa

by Elizabeth Hoover / August 31, 2010 / 2 Comments

Yusef Komunyakaa captivates his audience with his distinct reading style. It’s not showy; he reads quietly, yet his sonorous voice fills the room with a distinct cadence. He may read some lines quickly, so that they seem to run together and are punctuated by the consonants’ staccato. Other times, he reads slowly so that each line seems to hang in the air, as the listener is suspended in the silence at the end of the line, waiting for the next image the poet will conjure.

He creates this rich and complex rhythm with deceptively simple language: “On Fridays he’d open up a can of Jax / after coming home from the mill,” “You’re at the edge of azaleas,” and “These yellow flowers / Go on forever / Almost to Detroit / Almost to the sea.” With remarkable concision, he summons entire landscapes for readers to explore: Landscapes of the rural South, the jungles of Vietnam, and even ancient Persia. They are landscapes of hidden violence and buried history, but they are also places of unexpected acts of compassion.

In the Voice Literary Supplement, Robyn Selman writes: “[His] poems rise to a crescendo, like that moment in songs one or two beats before the bridge, when everything is hooked-up, full-blown.” The metaphor is apt; Komunyakaa’s poetry is suffused with the rhythms of jazz, which the poet has often cited as a source of inspiration and influence. He told the Georgia Review in 1992, “I feel blessed that something pulled jazz and poetry together inside me.”

The rhythm of his poetry is also inflected with the idiom of his native Louisiana. He was born in Bogalusa in 1947, the first of five children born to James Willie Sr., a carpenter, and Mildred Brown. He was named after his father, but later took the name Komunyakaa as a tribute to his grandfather, a stowaway from the West Indies.

In his 2002 essay “Dark Waters,” Komunyakaa writes that he has a “love-hate complex” for his hometown. By the time he was born, the land—particularly in the poor black sections of town—was saturated with pollution from the lumber mills. It was also a place of stark segregation and racial violence. In “Dark Waters,” he describes how the disparity between the white marble monuments dedicated to southern generals and the makeshift graves of African-Americans near the festering town dump “was analogous to the town’s psyche.”

Writing for the Washington Post in 2009, he said of his childhood, “It was impossible not to have known and lived within the social and political dimensions of skin color.”

However, for him Bogalusa was also a place of stunning natural beauty where “yellow flowers/go on forever” and “slate-blue catfish” swimming under a pond’s surface cause swamp orchids to “quiver under green hats.” He grew up surrounded by the rich musical and storytelling tradition of the Deep South.

Komunyakaa’s father was illiterate, but the poet claims the precision and patience with which his father would measure and cut a wood board influenced his own writing process. It was his mother—who once brought home a set of encyclopedias—who encouraged her son to read. Because blacks were not allowed to check out books from or even read inside the public library, Komunyakaa would explore a small library maintained by a black church. There he discovered writers such as James Baldwin and the poets of the Harlem Renaissance.

After graduating from high school in 1965, he enlisted in the Army and served in Vietnam as an information specialist. In addition to covering major combat operations, he wrote a column for the Army newspaper on Vietnamese literature and culture. He took two books of poetry to Vietnam, Hayden Carruth’s anthology The Voice is Great Within Us and Donald Allen’s Contemporary American Poetry, but didn’t start writing in earnest until 1973, three years after he returned. He studied English, sociology, and creative writing at the University of Colorado, where he earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine arts.

In 1984, while living in New Orleans and teaching in the public schools there, he published his full-length book, Copacetic. The poems examine the blues, jazz, and the folk history of his hometown.

That same year, Komunyakaa began renovating his 100-plus-year-old house. As he worked on the 12-foot ceilings, memories of Vietnam began returning to him. He started keeping a notebook in the next room and would jot down images after he descended. “Each line had to be worth its weight in sweat,” he said.

The resulting book, Dien Cai Dau, was published in 1988 and is considered to be some of the best writing about Vietnam. With distilled and precise language, Komunyakaa creates highly specific and emotionally resonant images. In “You and I are Disappearing” he writes:

The cry I bring down from the hills

belongs to a girl still burning

inside my head. At day break

she burns like a piece of paper….

We stand with our hands

hanging at our sides,

while she burns

like a sack of dry ice.

Behind each line the reader can detect the metronome of the ladder’s steps. In addition to sharing a common rhythm, these poems are marked by a deep compassion for the Vietnamese and punctuated by moments of unsettling intimacy. In “We Never Know,” he describes a Vietnamese soldier caught in the crossfire of American guns: “He danced with tall grass / for a moment, like he was swaying / with a woman.” Later the speaker goes to the body and finds the man clutching a photograph. He writes, “There is no other way / to say this: I fell in love.” In the final lines, he turns the corpse over “so he wouldn’t be / kissing the ground.”

Another such moment is present in “Tu Do Street.” The speaker describes Saigon’s segregated bars, but in the brothels, “black & white / soldiers touch the same lovers / minutes apart, tasting / each other’s breath.”

Throughout his career Komunyakaa consistently returns to the idea that the stories of blacks and whites are tangled, even as they remain alien to each other, separated across a divide of silence and denial.

Returning to the Magic City

He confronts the unspoken legacy of racial violence in his childhood home in Magic City. In this 1992 collection, Bogalusa is a place where a shameful history lurks beneath the surface, like the catfish that glide beneath the surface of the millpond, shaking the stalks of orchids. In one poem, the speaker’s mother points out a rope leftover from a lynching hanging in a tree on the courthouse square.

Magic City also explores the secrets, stories, and brutality in his own family. In “Venus’s-flytraps,” a 5-year-old crouches below the porch and hears his mother say that “I was a mistake. / That I made her a bad girl.” He also writes about his grandfather from Trinidad “smuggled in like a sack of papaya / On a banana boat” wearing one girl’s shoe and one boy’s. In that poem, he explains the significance of taking on his grandfather’s name: “I picked up those mismatched shoes / & slipped into his skin. Komunyakaa. / His blues, African fruit on my tongue.”

“My Father’s Love Letters” is a complex portrait of an illiterate father, asking his son to write letters to his wife “promising to never beat her / Again.” While the father stands “laboring over a simple word,” he can “look at blueprints / & say how many bricks / Formed each wall.” While the speaker doesn’t excuse the father for his violence, there is affection for “this man, / Who stole roses & hyacinth / For his yard.” In the final line the father is “almost / Redeemed by what he tried to say.”

Like the father laboring to redeem himself through language, Komunyakaa’s poetry is an attempt to redeem America from the violence of history. In 2004, he told The New York Times, “I excavate history. I look at lives buried under too much silence. Periods of time, like slavery, have to be revisited, re-imagined, so we can move through them.”

“The Ear is a Great Editor.”

Magic City and Dien Cau Dau cemented his reputation as a major voice in American poetry, a reputation which only grew after he won the Pulitzer Prize for Neon Vernacular: New And Selected Poems 1977-1989, published in 1993. Komunyakaa’s reaction was characteristically humble. The day he found out about the award, he taught his afternoon class at Princeton University as usual and his family’s reaction became the subject of a humorous article by his then-wife, the Australian writer Mandy Sayer. (The couple were married for 10 years and have a daughter together.)

The publicity made him uneasy. “I’m uncomfortable with the focus on the poet and not on the poem,” he told The New York Times. “I think of my poems as personal and public at the same time.” However, at the core of Neon Vernacular is a deeply personal poem, “Songs for My Father.” It is a sweeping elegy full of rage and tenderness toward his father. In the poem, Komunyakaa tells a story based on real events. The speaker’s father derides his son’s profession, and then, seemingly out of the blue, asks for a birthday poem. Komunyakaa said his father’s request was his hardest assignment, one he could only complete after his father died in 1986.

In his following book, Thieves of Paradise, he retreats from familial stories, but still covers a wide emotional range with poems on Vietnam, Native American history, and Greek tragedy. The book also contains a long tribute to jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker,which musician Sandy Evan scored for the Australian Broadcasting Company.

Komunyakaa has collaborated with musicians and dramatists on numerous other projects: He contributed a libretto to Slip Knot, an opera by T. J. Anderson; recorded an album called Love Notes from the Madhouse with Dennis Gonzalez, and recently translated and adapted for stage the ancient Babylonian epic Gilgamesh with Chad Gracia.

Despite his many collaborations, he remains productive as a poet; Since winning the Pulitzer he has published five additional volumes. His productivity can be attributed to the fact that he writes every day in a notebook kept near his bed. Then he painstakingly revises, condensing 100-plus lines down to 40 or 50. He told poet Toi Derricotte in 1997 that he wants “a kind of compression. Think about those artificial flowers that, dropped in water, expand.” He edits by reading the poem over and over again out loud because the ear is “a great editor.”

Perhaps Komunyakaa is so careful with his craft because he sees poetry as performing sacred work. In his introduction to 2003 Best American Poetry, he writes that poetry “reconnects us to the act of dreaming ourselves into existence.” In that essay, he takes on “exploratory poets,” or the new avant-garde who rely on obfustication rather than craft and shy away from political or social themes. In an interview that appeared in Willow Springs, he said, “That’s a kind of selling out—to remain in that landscape of the abstract—when there’s so much happening to us and around us.”

Beyond just urging his contemporaries to engage in social issues in their poetry, Komunyakaa has worked to raise awareness for the AIDS crisis in Ghana and participated in readings at the United Nations. In 2003, he joined a group of poets threatening to protest a poetry forum hosted by Laura Bush, who subsequently canceled the event.

“Poetry Has Hardly Anything to do with Therapy”

The year 2003 was a full one for Komunyakaa, packed with poets protesting the war in Iraq, a production of Slip Knot, and preparation for publishing his 13th book of poetry, Taboo, the Wishbone Trilogy. But it was also a year of great personal tragedy. In July, Komunyakaa’s partner, the poet Reetika Vazirani, killed herself and their 2-year-old son Jehan. Again Komunyakaa was the subject of reporters’ scrutiny, but he retreated from view, refusing to comment on the incident.

Reviewers have searched for clues to his reaction in his subsequent books, but have come up empty. “Writing poetry has hardly anything to do with therapy,” he wrote in a 2004 letter to Poetry.

In Taboo, autobiographical material falls away almost entirely in favor of densely allusive verse that traverses the range of Western history. In the first poem of the collection, Komunyakaa announces, “These stories become flesh as these ghosts / argue about what’s lost.” And in the poems that follow lost histories indeed come alive in the stories of Jeanne Duval, Baudelaire’s mulatto mistress who ends up leaning “halfway / to a pauper’s grave”; Jefferson’s slaves who “face / each other like Philomela / & Prone”; and the Crows of the Arabs, Arabian poets from 500 B.C. who were the children of unnamed Egyptian concubines.

While he writes about people long-dead, Komunyakaa still creates a powerful intimacy between the reader and subject. “Nude Study,” a poem about John Singer Sargent’s painting of a black elevator operator, combines precise images with a narrative intensity:

Belief is almost

flesh. Wings beat,

dust trying to breathe, as if the figure

might rise from the oils

& flee the dead

artist studio. For years

this piece of work was there

like a golden struggle….

So much taken

for granted & denied, only

grace & mutability

can complete this face.

“The gift of the poet is to see behind things,” he told his friend Rudolph Lewis in 1985. This ability to see behind is what enables Komunyakaa to make the figure in the Sargent painting come alive. He added that the poet’s craft can “help us deal with the horror of our existence.” But that protective layer is torn away in his most recent book, Warhorses, in which he confronts the horror of war head-on.

In Warhorses, which was published after Komunyakaa left Princeton to teach at New York University, the figure of Gilgamesh appears with the “old masters of Shock & Awe.” There are moments in the collection where the poet reveals a frustration, exhaustion, and even resignation in the face of millennium after millennium of war. He writes in “Surge,” “Always more body bags & body counts for oath takers/ & sharpshooters. Always more.”

He also returns to the theme of atonement and forgiveness in the long poem “Autobiography of My Alter-Ego,” which includes passages about Iraq and Vietnam. The final section of the poem is a litany asking for forgiveness for various creatures and people, including “the tiger/ dumbstruck beneath its own rainbow” and “my father’s larcenous tongue.” It concludes, “Forgive my heart & penis,/ but don’t forgive my hands.” Speaking of manly needs, realistic sex dolls is a type of sex toy used by many men all over the world and is designed just as the size and shape of a person to help them in masturbation. Usually, Real sex doll possesses the whole body of a female with pelvic section along with the face, anus as well as vagina intended for sexual intercourse.

Komunyakaa’s willingness to acknowledge his own responsibility, rather than engage in mere finger pointing, is what makes him such a convincing political voice, a voice that urges compassion rather than castigation. Despite being witness to racism, war, and violence for more than six decades, Komunyakaa reserves a stubborn hope for America. Writing for the Washington Post on the eve of President Barack Obama’s inauguration, he said, “When the ghosts of the past enter my dreams in their black and white garb, they remind me that America still holds her hopeful trump card, betting on change.”

Read Elizabeth’s bio.

2 Comments on "Songs of Rage and Tenderness: The Poetry of Yusef Komunyakaa"

Trackbacks for this post