“A Very Funny Nightmare:” A Q&A with Oleh Shynkarenko

by Bret Anne Serbin / August 10, 2016 / No comments

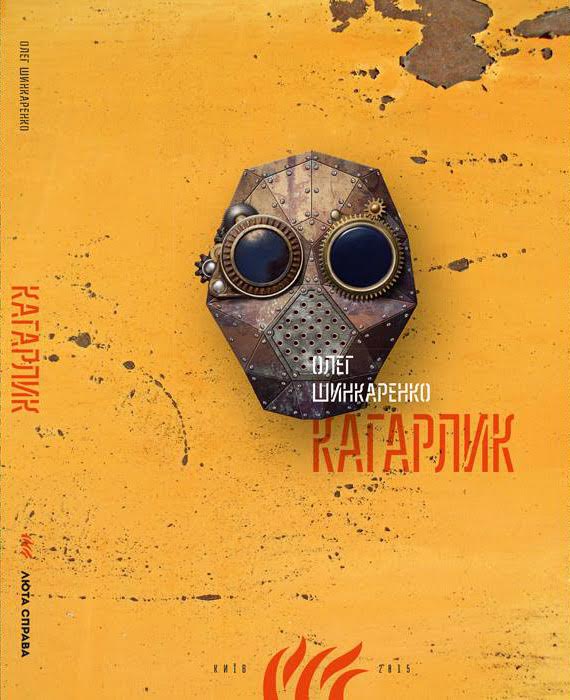

Image courtesy of Oleh Shynkarenko

In the midst of the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution, Ukrainian writer Oleh Shynkarenko published Kaharlyk, a dystopian novel with a dark vision of Ukraine’s future. Two years after the political upheaval in Ukraine, Kaharlyk is coming to English-speaking audiences for the first time. The novel, which was written in 100-word Facebook posts after government officials censored Shynkarenko’s blog, will be published in its English translation in September. In this interview, conducted via email with Sampsonia Way, the unorthodox author discusses his unique writing process and Ukraine’s complicated national identity.

Literature & National Identity

Kaharlyk was originally published in 2014, but the English translation is finally due out in September. What is the significance of bringing this Ukrainian story to English-speaking audiences?

My novel is not a diary of protest and war. It is fiction in a very unusual form: a conceptual work which, like any worthwhile art concept, is aimed to criticize the surrounding reality in an ironic way. I hope that English audiences will get a certain notion about Ukraine far beyond the daily news stream. I am afraid that English-speakers will not always understand the subjects of my jokes, because every nation has its own, often very unexpected, targets for humor and satire. But recalling my own experience with reading Mark Twain or Kurt Vonnegut I would say that I never felt any misunderstanding with their humor.

I also hope that my novel will bring Ukrainians closer to those English-speakers. I am not a usual Ukrainian, but Mark Twain or Kurt Vonnegut were not usual Americans either. (To the point! I read a funny story in Vonnegut’s “Palm Sunday” that some American schools in 1970 regularly burned his books as immoral. So he definitely was considered unusual, but still representative of American literature — sounds like an oxymoron).

It is a question for me too: does some Ukrainian humor really exist? Do we have some unique national concepts which could appear as funny to foreigners? A nation exists only when it has something of its own to laugh at. When a country exports its jokes it exports its influence as well.

What are the most important things that you want English-speaking audiences to learn about what happened in Ukraine in 2014? What about what’s happening now?

It is a question of time. Kaharlyk is a real Ukrainian town next to Kyiv, where in my novel time stood still forever. In other Ukrainian regions time is slowed down in different degrees, due to a Russian fantastic weapon test. Of course this is a metaphor. Russia slows down time in Ukraine, trying to drag us back to the USSR or even to the times of the Russian Empire. Moscow uses a lot of techniques to achieve this, and it is not a metaphor.

For example, they used the first Soviet astronaut Yuri Gagarin’s smile. Some people said: he smiles so nice and kindly because the USSR was nice and kind too. They said that since Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was smart and wise, the Russian Empire was smart and wise, too. “Which Ukrainian astronauts or poets do we know? No one. So there is no Ukraine,” Russians say. That absolutely irrational way of thinking is typical for most people in Russia and some people in Ukraine.

What happened in Ukraine in 2014 was a struggle against such irrationality based on lies and ignorance. Ukrainians tried to break from that frozen past time, when the past, the present, and the future were always in the past. And they succeeded. But the Kremlin Fridge is still determined to freeze everything within its reach. That war is only the cold spread from Moscow and some naïve, cheated people think that it is warmth. We struggle not to fall into the abyss of the frozen past. The Kremlin’s time machine is broken and affects us badly.

How does the impact of the translation change given that two years have passed since the Ukrainian revolution?

Of course my novel is related to the Ukrainian Revolution, but it is not about it. Don’t forget that I started writing in 2012. When the revolution erupted my novel was almost finished. It sounds like something “Oscarwildian:” reality as an echo of a fantasy. I hope that the lasting impact of my book is in its revolutionary form and language. Maybe the impact of my book will be influential for a decade until the next big talent eclipses it. I would like people to reread my book, maybe just in fragments, because it is fragmented.

Writing Process

The most noteworthy aspect of Kaharlyk is its composition via 100-word Facebook posts. What was it like for you to write a story through such a unique process?

It was a challenge. The main problem when you write a novel is to work on it regularly and to avoid odd, superfluous words. So I decided to write 100 words every day to be concise and to work faster. My text looks like combs and readers could wait to find honey there. But I would not say that I managed to stick to the rule throughout all of my book. Sometimes combs stick together into constellations. I hope that is not because there is too much honey in them.

And of course, Facebook was a unique platform. I dared to use the social network to promote my book before it was created and to have some dialogue with my readers in the process of creation, because they could comment and advise me. I hoped to produce audio and video as well to have it all as multimedia project.

To what extent was writing Kaharlyk in Facebook posts a stylistic decision?

Actually the conception of 100-word fragments was quite decorative. You may notice that often the separation between fragments is only nominal. But of course, the restriction formed and limited or configured my thoughts in some way. I tried to write with dictums, maxims, and gnomes, or meaningful sayings put into verse. Sometimes the fragments seemed too serious, so I created absurd, quasi pensées to deconstruct them, exploding them from the inside. And sometimes writing in fragments led to interesting results which were not easy to translate. For example: “With his acute sense of justice, the deceased differed from ordinary folk.” I am afraid that Stephen, the translator, had a lot of problems with my tightrope-walking. But he is a professional, and he turned my Ukrainian book into an English one.

I understand that you chose this form of writing in order to avoid censorship during the protests in Kiev. Why is Facebook a safer platform and a better medium for resistance than a blog?

I would not say that I wrote my novel on Facebook only to avoid censorship. There were other reasons which I have mentioned. But of course Facebook is much safer than the blog service LiveJournal, which was purchased by Russian tycoons related to the Kremlin.

In 2010 I posted a foolish joke about our then-president Yanukovitch on my blog and was invited and interrogated by secret service police. My entry mysteriously disappeared the same day. I imagine the exchange went something like: “Hey, guys, could you delete a post of a blogger? You know all his passwords anyway.” And those in Moscow answered: “Of course we can! Would you like us to delete his whole blog account as well?”

After that, I left my blog and moved to Facebook, because it was safer. Nobody could call the Facebook office and ask them to delete my novel. And that coincided with the decline of blogosphere around the world in 2010. When I was a blogger I had twenty to thirty readers and a comment once a week from them. Now I have 2,579 friends and 408 followers, and I’ve received 1,578 comments in one year. One of my photos got 1,618 likes. And no police or Russian KGB can delete my entries. But today I am trying to avoid foolish jokes. Resistance can be inventive and wise.

How did the writing process for Kaharlyk compare to writing your previous book, How to Disappear Completely?

How to Disappear Completely was actually a short-story collection. I wrote it from 1994 to 2006 in an idle way. I never thought that somebody would want to publish it. There was no goal for me. That was a collection of random impressions of a young man who tends to be impressed by some casual details and events of his life. It was strongly influenced by writers I read in those times. I was quite absent minded then and had not found my topic yet.

What was the editing process like for adapting these posts into Kaharlyk’s novel format?

When I had written twenty-five percent of my book online, I had found a plot and characters. The book was in my mind, so I decided to continue it as an ordinary manuscript in Google Docs. It was even more convenient, because it has a word count. And you can read the text from top to bottom, unlike Facebook.

Kaharlyk is also distinctive because of the additional multimedia elements, such as the sounds of washing machines and cows mooing. Why did you include these added features? How did these extra pieces affect your composition process?

These sound design fragments were only ornamental elements to promote my book. But now I use them in presentations. My idea was to create music not as a musician, but as an unconscious medium, so that the melody does not come from a player, but from the space itself. The space makes sound anyway, but in a chaotic way; one needs to put it in order a little bit. Any art is putting empty space in certain order.

Reception

In those two years since the Ukrainian Revolution and the original publication of Kaharlyk, what reactions have you had from your Ukrainian readers?

I’ve had a lot of different reactions! From “that pupillary novel” (as “a rock-star of the Ukrainian literary hangout” said) to “that amazing book” (as my artist friend wrote). I’ve had a lot of professional and amateurish reviews for my book and yet it is still almost unknown in Ukraine. I am definitely not in fashion. So what? Hype is a synonym of trick. Usually you need to swindle your audience in some way if you want to sell more copies. The truth is very bad for sales. Often it looks like something peculiar and fantastic, too strange to have in your bookshelves.

How have Ukrainian authorities responded to the novel?

They did not read it. But there are some Ukrainian diplomats in Berlin, Vienna, Bratislava and Vilnius who visited my book presentations in those cities. They understood my book and liked it. One of them in Vilnius (we were at the Venclova Family Museum) was quite discerning. He caught the sense of my metaphor even better than I. It was about “morphones,” gadgets that can back up people’s minds. The main difference between the copy and a real person is that the copy never changes. “I know a lot of people that act like those morphones,” he said. The mind is another frozen thing in my novel.

Ukrainian Politics Then & Now

Ukraine is notorious for the state of free press. As a journalist, an artist, and an author, how have you personally experienced media censorship in Ukraine?

Happily, the worst period is over. I remember my work for an information agency in 2010. As an editor I had a “black list of opposition politicians” worked out by our director. He explained to us how to use it: “You should not delete them from news stream at all, because it will look strange. Publish only the most important of their quotes.” Actually it meant that we should balance the news like eighty percent from power and twenty percent from opposition. And the next day the director said: “That politician is not worth mentioning at all. Remember this and that, because we cannot write it down, you know.”

We had completely different relations with politicians from power. I remember that one of them visited our office when I worked in my night shift. The director said: “Make a coffee for our guest, please.” I was shocked, because I had to find, edit, and publish news online every ten minutes. But when we have such an important guest, work can wait. The guest was a notorious minister of education, who had once said: “Those plain people in western Ukraine have dirty hands, they did not wash them.” He often used hate speech and follies and sometimes we had to filter his words to save his public image. Another journalist and I got our revenge by publishing his next silliness and were fined for it. I was eventually fired for publishing a piece of news which a city mayor did not like. “How could you do that?!” the director asked me, “Didn’t you know that it is very unpleasant and disadvantageous for him? He is our best friend!” I suppose all these people paid the agency or were shareholders. Gradually almost all Ukrainian media turned into such kind of agency.

Kaharlyk is clearly connected to the 2013 protests in Kiev, but was there a particular event that inspired you to transform your frustrations with the government into this large-scale literary protest?

I’d say my novel is rather a child of the 2010 to 2012 stagnation than the 2013 revolution. Everybody felt a deadlock in 2012. We thought: “Can something be changed by 2030 or 2040? Looks like we are all freezing into an iceberg.” But of course there were several events that launched my novel. One of them was Jean-Claude Van Damme’s participation in Olexander Onishchenko’s pre-election tour in Kaharlyk. Yes, namely in Kaharlyk! Mr. Onishchenko, whose real surname is Kadyrov, ran for the MP’s mandate in 2012. To achieve his goal, he decided to do only two things: first, to change his name which is associated with the notorious Russian Chechen Republic leader. Second, to flabbergast Kaharlyk local residents. I suppose he ordered Mr. Van Damme’s services in some way. Participation by foreign artists in pre-election campaigns is absolutely banned in Ukraine. But Mr. Van Damme said: “I am here not because Mr. Onishchenko would like to get a place in Ukrainian Parliament. We are just friends.”

Of course Mr. Onishchenko won the elections. Now he has escaped to Russia, because, according to investigation, Onishchenko was accused of defrauding the state of three billion UAH. I don’t know if Mr. Van Damme got money from Mr. Onishchenko, but if he did, he got money stolen by a swindler of the poor Ukrainian people. I thought then: what a story! Kaharlyk local residents are ready to vote for anybody who can show them a US film star from the 1980s! These people literally live in the 1980s! Time stood still in Kaharlyk. This is an amazing story and I definitely should write a novel about it. Of course there is no Van Damme in my book. I found other metaphors to represent the idea.

In the story itself, memory is the main character’s central concern. Why is this memory of one’s own past and the history of Ukraine so significant in the context of the political situation in Ukraine?

Sahaydachny, the protagonist, lost his memory of Ukrainian society. Memory restoration, recalling, is an active and purposeful process. It is much more difficult to reclaim your memory than your lover, which creates high tension in the plot of my novel. And then I decided to combine these two quests: searching for lost memory and the lost lover. Sahaydachny is trying to find his wife and he is sure that his memory will come back with his wife.

But Ukraine should return its memory too and not only in my novel. A lot of crimes against Ukrainians were classified in the KGB’s archives. Just imagine: from 1933 to 1937 Soviet authorities arrested and killed several hundred Ukrainian writers and other intellectuals. We call it the Executed Renaissance. It was forbidden to even mention it. Almost nobody knew their names till the USSR collapsed. I did not hear about the Executed Renaissance until 1996. It was a Russian crime against Ukrainians. They were going to eliminate our culture; they executed the cream of our nation and forbade even memories about the tragedy. Forbidden and lost memories of crime is another topic of my novel.

The future of Ukraine that Kaharlyk presents is incredibly dark and dystopian. Two years after the protests and the novel’s publication, has your vision of the future of Ukraine changed at all?

It is not my forecast, because I am not Baba Vanga. It is just a metaphor in the form of a vision. I just exploited the popular dystopian genre to bring my ideas to a larger audience. My goal was not to predict the future, but to criticize the present. But if, back in 2012, I could imagine our future only in doomed tones with satirical semitones, now my imagination of the future is quite unpredictable. I am writing my fourth novel Bolshye Chervi (it is a toponym of Big Worms) about Russian mercenaries going to Ukraine in a tank painted as a holiday teapot to “mow dill,” a Russian euphemism for killing Ukrainians. Everything looks like a very funny nightmare. Like our life.

Personal Life & Further Reading

You have remained in Kiev throughout all the turmoil. Did you ever consider leaving?

No, I was sure that everything would end well. Ukraine is too big to be frozen for several months. When the war started and there was a threat of Russian invasion, we moved for a month into western Ukraine.

One could be killed of course, but only in the city center in a small circle around 1,500 meters. There was a paradox noticed by Bruce Sterling, who visited Maidan a couple of days after February 20, 2014, when more than 100 people were killed by police. He told me about it: “The city is safe and sound. Destructions are localized in a very small spot.” And again, I was a freelancer then, working for The Daily Beast, writing about every day and hour in Kyiv. I did not feel any oppression then.

How has your life there changed in the aftermath of the political upheaval?

As a journalist I’ve had the rare opportunity to contribute to foreign media. I worked for The Institute of War and Peace reporting as well, and I’ve got a grant to make a policy paper “Ukrainian Media after Euromaidan.” I worked as an intern in Bratislava. I started my own radio podcast “Philosophical Drum.” The cold period was over with new hopes, but the Kremlin Fridge ran amok with anger and started the war.

How has your life changed a result of your novel’s international fame?

I would not call it fame, because it has not even been translated yet and nobody has read it, except for my translator, Stephen Komarnitskyj. But I hope that other English-speaking readers will be of the same opinion about my book as he is. He said, “Ukraine has one of the most powerful literary and artistic environments in Europe. These authors are experimenting, playing with the form. The novel Kaharlyk testifies to that.”

Kaharlyk is advertised as a way to “help Ukraine’s voice be heard.” After Kaharlyk, what are some other important Ukrainian books, blogs, or other media that attempt to share Ukraine’s voice with the world?

There are some names which are worth translating and presenting throughout the world. They are writers Oleg Kotsarev, Taras Prohasko, Julia Stahivska, Bogdan-Oleg Horobchuk, Tanya Malyarchuk, Myroslav Layuk, Anatoly Dnistrovyj, artists Olexandr Roitburd, Nazar Bilyk and Ivan Semesyuk, filmmaker Kira Muratova, and the band Vivienne Mort.

There is also an interesting Ukrainian blog which is an online calendar of repression, arrests and shootings of Ukrainian intellectuals in the 1930s. It was made to restore Ukrainian memory. For instance, on July 13, 1937 Ukrainian painter Michael Boychuk and his four students were killed by Soviet Secret Police NKVD. The artist and his students were accused of “counterrevolutionary Ukrainian national-fascist activities and rejection Ukraine from the Soviet Union to create Ukrainian national-fascist state.” Of course, all these allegations were a complete fabrication. Russian authorities just wanted to eliminate original Ukrainian painters in order to say: “There are no interesting painters in Ukraine, so there is no Ukraine.”

Since Kaharlyk’s initial publication you have started working at the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union (UHHRU). Can you tell us a little about your work there? How does this new project connect to your literary protests?

I work for the UHHRU as a journalist writing about criminal proceedings and court sessions in which its lawyers are involved. It is a kind of Public Relations job. Lawyers apply to the European Court of Human Rights and when they succeed, I portray the story.

It influences my work because my fiction is always a mixed puzzle of reality. The most fantastic story is constructed from a banal daily routine. Now I am working on an episode in which a gangster commits robbery while quoting European Convention on Human Rights to show that his actions have legal ground. Of course it is an allusion to my favorite, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” a short story written by Flannery O’Connor, in which a gangster quotes the Bible. It is very interesting work at the UHHRU because it deals with people’s stories. I will use some of them in my new novel.