Filmmaker Laura Varela, raúlrsalinas, and the Poetry of Liberation

by Joshua Barnes / April 29, 2014 / No comments

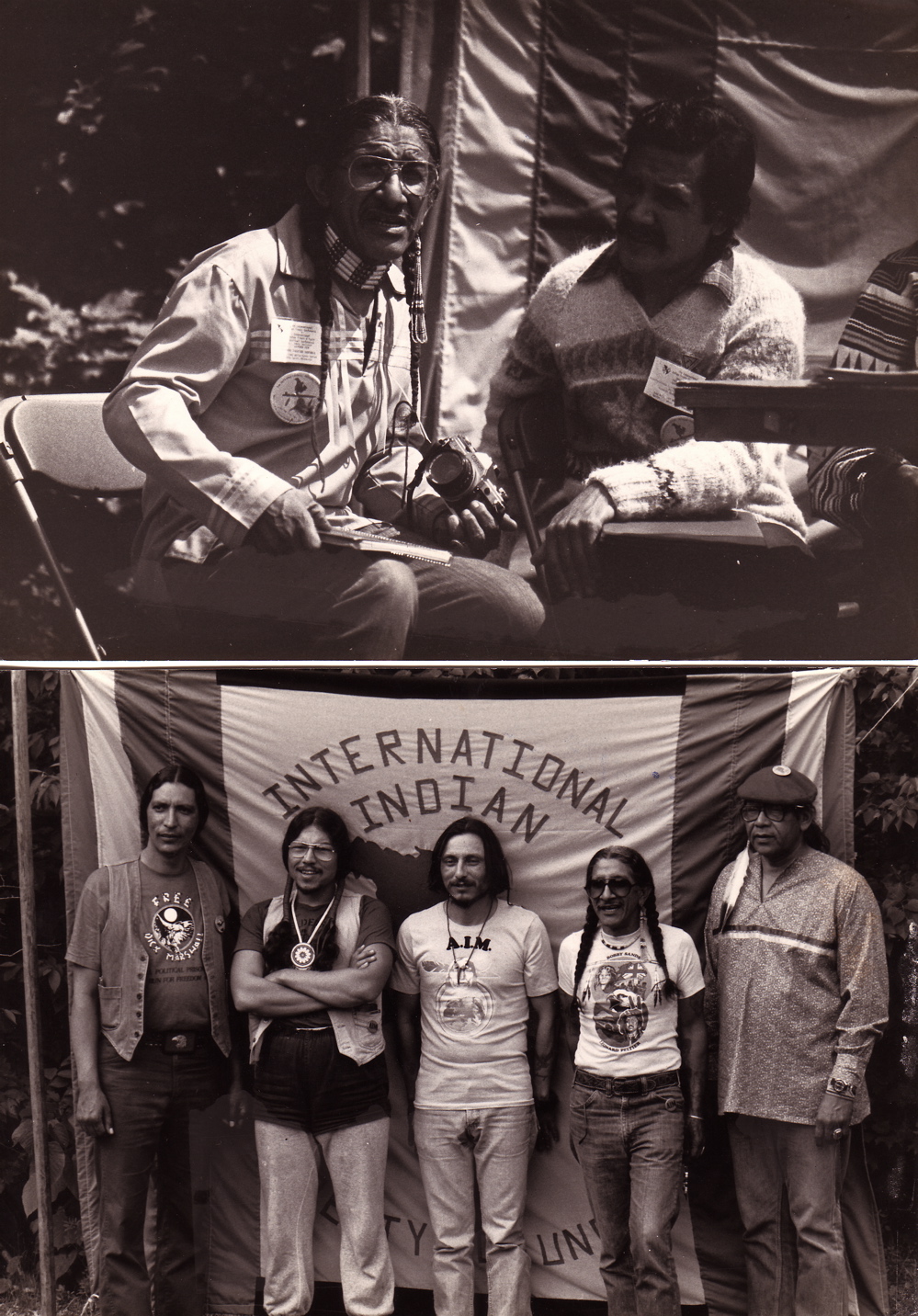

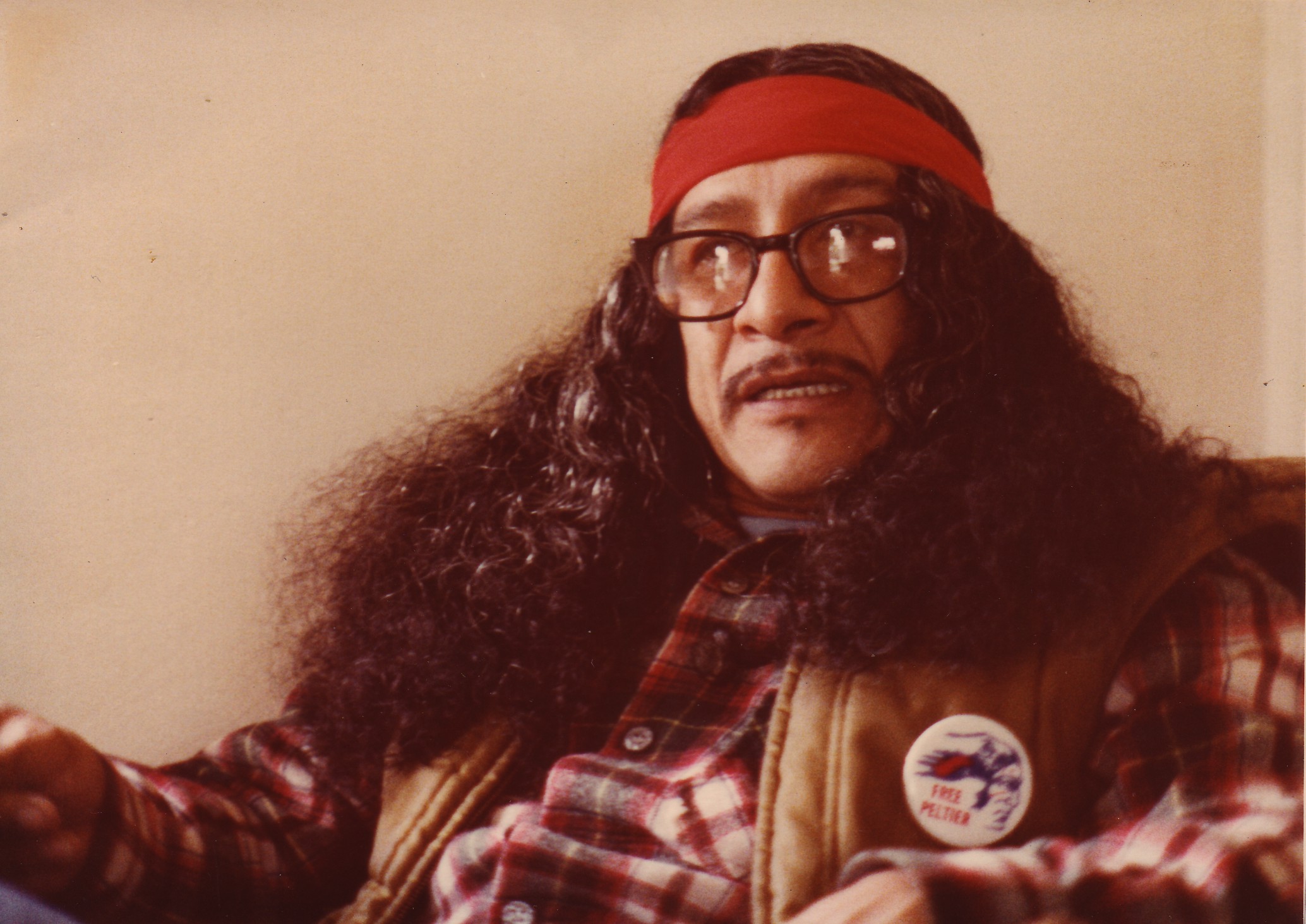

Poet activist raúlrsalinas in the 1970s, after his release from prison. Photos courtesy of Laura Varela via raúlrsalinas personal archive.

Laura Varela didn’t always want to be a filmmaker, but after she left a painful youth in El Paso for classes in feminism and Chicano history at the University of Texas Austin, her world-view was radically altered. For one thing, at UT Austin she says she discovered Chicano film and “the power it had to raise a collective consciousness.” To that end, Varela’s first film, which profiled Herminia Tecíhtzin Enriquez, one of the founders of San Diego’s Chicano Park and premiered at Guadalupe Cultural Arts’ CineFestival 20 years ago, started a long line of historically- and socially-conscious work that includes the documentary As Long as I Remember: American Veteranos, and “Enlight-Tents”, with German artist Vaago Weiland, a site-specific public art installation at the Alamo.

Austin, Texas is also where Varela met the subject of her current film-in-progress, raúlrsalinas and the Poetry of Liberation. When she met raúlrsalinas in the early 1990s, he was operating the Resistencia Bookstore, performing his vibrant, radical poetry, and running a writing program for at-risk youth. However, his life before Austin was a harrowing path of petty crime, imprisonment, and rebirth that lead to activism with communities as diverse as Native Americans in Seattle and Black Panthers in Kansas. Two years before his death in 2008, salinas asked Varela to produce a documentary on his life, officially recording the history of an important Chicano poet about whom little has been written. In the pre-release footage of raúlrsalinas and the Poetry of Liberation, which follows salinas from poetry readings to afternoon drives through his old barrio, Varela’s unadorned, hand-cam shots provide a sensitive, intimate view into the poet’s life.

To understand more about the film and its charismatic subject, Varela spoke with Sampsonia Way by phone in February. In this interview she talks about why raúlrsalinas is mostly unknown, how he grew from street criminal to dynamic poet and radical coalition builder, and why she feels Latinos are practically invisible in the United States today.

Let’s talk about why you decided to make raúlrsalinas and the Poetry of Liberation. How did the idea come about?

I’ve known raúl since the 90s when I went to school at the University of Texas Austin and visited his shop, the Resistencia Bookstore. He was one of my first mentors. Part of the trailer for the documentary was shot at a poetry reading at Resistencia. In 2006, after a long time of being apart, I saw raúl again. He came up and asked me, “What are you doing? Where have you been?”

I told him I’d been having babies and he said he wanted to talk about a project.

A few days later I found out that he wanted to make a film about his life. Once I knew that, there was no question about doing it. I think he felt comfortable asking me because we could collaborate and he could get what he wanted, but I still felt very honored. When an elder asks you to do something like that you shouldn’t say no. Then we started really quickly, filming without funding and writing proposals for developmental support.

- Laura Varela

- Laura Varela is a San Antonio-based documentary filmmaker and media artist whose work as a storyteller is shaped by her roots growing up on the US/ Mexico Border in El Paso, Texas.

- She is currently developing the PBS documentary raúlrsalinas and the Poetry of Liberation, about the life and times of the Xicano poet and activist. In March 2009 she created the public art installation “Enlight-Tents” at the Alamo with German artist Vaago Weiland. Her installation work has been exhibited at the San Antonio Museum of Art, Blue Star Center for Contemporary Art, The Esperanza Peace and Justice Center, Gallista Gallery, and the UTSA Downtown Art Gallery.

- She is a fellow of the 2006 CPB/PBS Producers Academy, the 2006 NALAC Leadership Institute, and the 2003 NALIP/UCLA Latino Producers Academy. She attended the Sundance Filmmaker’s lab in 1997 and in 1993 received her Bachelor of Science from the University of Texas in Radio TV and Film. Artist Residencies include Swarthmore College, PA, Art for Change in NYC, and the Hoschule Neiderrhein and Faust Academy in Germany.

Aside from your personal connection to raúl, there’s another reason for making the film: Very little information exists about him online, aside from a few brief biographies and poems.

Exactly. He also has three spoken word CDs, but you can’t get them anywhere digitally. If you go to his bookstore, you can find copies, but I don’t think you can get that work online. You probably have to pick up the phone and call Resistencia to get his CDs and books shipped to you.

In light of that, I should add that any time raúl traveled he was really well-received by Native American communities, activist communities, and progressive communities all over the world. While he did receive a Lifetime Achievement award from NALAC in 2004 and the Alfredo Cisneros Del Moral Foundation award in 2007, for the most part in San Antonio, and elsewhere in Texas, he was neither honored nor recognized to the extent that he should have been for the literary and social work he did. A book of his writing in prison, raúlrsalinas and the Jail Machine: My Pen is My Weapon, is taught at universities, but he was just too progressive.

Still, there are many famous, radical poets who have been canonized. Why do you think raúl has been mostly overlooked by history?

Latinos in particular have lost their sense of culture and identity. If you want to know what it’s like to be Latino in the United States today, you should know that we have no idea who we are. We have no idea about our Native American roots in cultures like the Maya, the Mixtecos, Apaches, or the Mission Indians. We don’t know the history of our revolutions or our food. We think of Native Americans as communities on the Rez, in particular regions, and we’ve been so far removed from our culture that we don’t realize that the people labeled “Native American” are us. We’re apathetic toward the Native American community and their struggle, but raúl realized what he was early in life, and took on that struggle.

The way you speak about this loss of history makes me think that you went through a comparable process of discovery. What was that like for you?

It was so liberating. I’m Mexican-American, but I’m light-skinned, and growing up in El Paso, Texas I was always bullied in the barrio because of that. In addition, even though my school was 99% Mexican-American I never learned anything about Mexican-American history until I went to college and took a Chicano studies course.

When I went to college I also took feminist courses and a lot of injustices that I couldn’t quite pinpoint or articulate began to make sense. It was the first time I saw Chicano film and the power it had to raise a collective consciousness. I saw the amount of people that film could reach and while I’d wanted to be a radio journalist and an activist, I discovered that film could encompass both of those interests. By approaching issues through the lens of the human, through a person with real-life experiences, you can explore topics in a way that people don’t have any way of communicating. I always want to find and explore the human in my work.

What did you learn about raúl in the process of making the film?

I learned that I didn’t know anything about him. raúl was so much more than just a poet. I didn’t realize how important he was for the Prisoner’s Rights Movement in the late 60s and early 70s; how important he was to the Chicano Rights Movement in the Northwest and the Native American fishing rights struggle in Seattle; not to mention the work that he did with the Leonard Peltier Defense Committee and documenting a lot of his extremist students’ poetry. At a time when FBI was infiltrating a lot of radical movements of color he was in the trenches. I had no idea about any of this. And then there was the work he did with the International Indian Treaty Council at the UN. All of this activism started in prison.

While he was imprisoned raúl would write to the Human Rights Commissioner of the UN about human rights abuses in the American prison system. He’d write down pieces of what was going on during prison riots and work it out on toilet paper while they were being smoked in. He wrote a lot in prison and learned coalition building with groups like the Black Power Movement, the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, Native Americans—the list goes on and on. He was also locked up with Rafael Cancel Miranda, an Independentista, who, along with other revolutionaries, shot up the House of Representatives to demand a free Puerto Rico. Miranda was a teacher who showed raúl a lot in prison.

If we simplify his trajectory, raúl went from being a kid who was originally locked up as a hoodlum for street crime to penning letters and declarations for radical movements and forming coalitions. He was a real intellectual agitator and the authorities considered him a threat. At this point he was in Leavenworth Prison in Kansas but eventually the authorities decided they had to get him out. They transferred him to Marion Federal Penitentiary, which housed political prisoners, and incarcerated him there as an agitator. But they paroled him quickly as there were some problems in Marion too. They wanted raúl out, and with the help of faculty and graduate students from the University of Washington at Seattle (UW) he was paroled, relocated to Seattle, and enrolled at the University. Within a year he was teaching courses in Chicano Literature at UW and had helped form El Centro de La Raza.

You can’t ignore the irony that raúl became much more dangerous to the establishment through his experience in prison.

After he was released he also went to Cuba with the El Centro de La Raza and brought a contingent of Native Americans from the Northwest to Cuba. There’s footage of that trip, which I’m hoping to incorporate into the film.

What was his philosophy about working with these disparate groups? On one hand you can see his actions as simply ‘anti-establishment,’ but there seems to be something deeper going on. What brought them all together?

The demand for the right to live their lives as people with dignity. This stemmed from being a person in this country and seeing what was happening to its land and its people as a result of the government’s treatment. As a kid raúl was really smart but he was constantly harassed by the white police. Throughout his life the administration just couldn’t handle him; he was too smart.

Clip of Laura Varela’s work-in-progress raúlrsalinas and the Poetry of Liberation. Video: Laura Varela.

On film his personality and energy are magnetic and impressive. What was it like to talk with him in person?

In person raúl was extremely thoughtful. He deeply considered the things he was going to say before he spoke. If you asked him a question about revolution or about a group or set of politics, the people around him would tune-in to the conversation because they wanted to hear what he had to say. He was very well read and was always thinking about liberation, freedom, and the end of oppression.

Also, every time we asked him about his transformation in prison—which, aside from his education on revolutions, the Spanish Language, and Meso-American history, is where he wrote his famous poem “Un Trip Thru the Mind Jail” after sleeping for 18 hours and waking up with it fully-formed in his head—he always cried. It was a very hard process for him; he consistently said that a person died there and a new person was born.

Did you go to his funeral in 2008?

I did. I filmed a little bit but I didn’t feel like it was appropriate. I just wanted to mourn.

Today the old guard of these movements—people like raúl and people who were first in the Chicano Rights Movement or the United Farm Worker Movement—have started to pass away. How is that political activism being continued by the next generation?

The program he created, Casa de Red Salmon Arts, has a youth program called Save Our Youth (SOY program), that does poetry and art clinics with at-risk youth in Austin’s inner-city schools, and sometimes at detention centers. Today the people who’ve taken up the mission are kids like him, who he trained.

There are also other organizations, like the National Association of Latino Arts and Cultures (NALAC), which helped you at two stages in your career, correct?

I was part of the NALAC Leadership Institute in 2006, which was vital in that it introduced me to best practices for arts organizations and artists. Also the collaborations and friendships that stemmed from that time were very fruitful. The grant they gave me for part of the development phase of raúlrsalinas and the Poetry of Liberation allowed me to thrive as an artist to research and flesh out the proposal.

Ultimately, what would you like people to know about raúlrsalinas?

raúlrsalinas was an American poet of the people.

What about Latino arts and the Latino community at large?

In terms of the mainstream, we’re almost invisible. People have no idea that we exist. And while our invisibility gives us motivation to create more and reach out to different audiences, people need to know that we’re here. We’ve never immigrated here; we’ve always been here. Even if recent immigrants within Salvadoran and Puerto Rican communities haven’t been in this country for very long, they’re still part of the fabric of American culture and they contribute a lot—we all do.