A Kiss in the Right Direction: An Interview with Nima Dehghani and Behzad Tabibian

by Adam Ernette / January 21, 2014 / 1 Comment

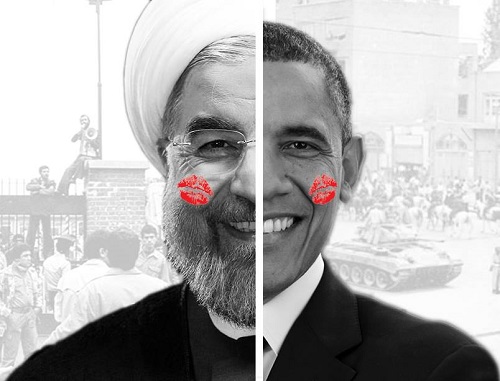

Promotional image for the Kiss for Peace Project. Photo via Facebook.

The Kiss for Peace Project—a social experiment created by Nima Dehghani and Behzad Tabibian—prompts Iranians and Americans to snap pictures of themselves blowing kisses and upload the photos to Facebook. The aim of the Kiss for Peace Project is to foster social interaction between the two countries’ citizens and show a collective desire to move beyond long-held political tensions.

Upon meeting in Tehran, Dehghani and Tabibian began working together on projects based on reconciling the relationship between the United States and Iran. Now living in the US, Dehghani is a graduate student studying fine arts at Carnegie Mellon University and Tabibian is a graduate student studying computer science at the University of Pittsburgh. They work together to create artistically driven projects paired with social media to spread their message of peace and understanding.

Dehghani and Tabibian sat down with Sampsonia Way in November to discuss the importance of social interaction between the two countries, the difficulties of challenging the stereotypical image of Iranians, and the ways in which censorship has affected their success.

Throughout the interview Dehghani felt more comfortable speaking in Farsi while Tabibian translated.

- Nima Dehghani

- Nima Dehghani is a multi-disciplinary artist whose work explores the relationship between society, art, politics, and audience interactions in social practices. Born in Tehran, Iran in 1986, he got his Bachelor’s degree in architecture in Iran, and is now pursuing a Masters of Fine arts at Carnegie Mellon University. He is a member of the board of Iranian Playwrights’ Association, member of International Federation of Journalists, and works as a writer, poet, and journalist with several magazines.

- Behzad Tabibian

- Behzad Tabibian is a Master’s student at University of Pittsburgh. He obtained his Bachelor’s degree in computer science in 2012 from University of Edinburgh, Scotland. He has extensive experience in software development, robotics, and artificial intelligence with several scientific publications in these fields. He is now focused on machine learning and adaptive systems with particular focus on data from social networks as they become ubiquitous in people’s daily lives.

How did you decide to work together?

Dehghani: I started these projects when I was in Tehran, but I felt it was better to continue with internet-based performance art, so when I came to Pittsburgh I asked Behzad to help me.

Tabibian: We saw potential in social networks.

Dehghani: We were looking for creative ideas to bring people into the discourse, and technology makes that possible. Most of the efforts in the past have failed because people were not as involved as they should’ve been. Instead of us defining their role we let them speak for themselves.

Tabibian: The biggest impact that projects like this can make is allowing all of us to see people’s ordinary lives.

Dehghani: These apparently superficial projects show that people living in these countries are no different from each other—the way they live, the way they work, and the way they dress are similar. These projects shift people’s perceptions. People outside of Iran are surprised we have Facebook and can dress the way we do. We want to make them as surprised as possible.

What do you call these types of projects?

Dehghani: If we had to find one title for this kind of art project it would be “social practice.” We’re using social media and participation under Netformance—an online project centered on participatory art—so it could have lots of names, though I prefer that critics, journalists, or someone else name this kind of art.

Who is the Kiss for Peace Project’s audience?

Tabibian: It’s for Iranians that cannot imagine what Americans think or look like. For Americans, it raises questions about whether they should trust what they read or see in the media.

Dehghani: Our audience is all people across the board—our participants are Iranian and American. We’re focused on the relationship between Iran and the United States, but we know that if these two countries can end their animosity toward each other it would be good for everyone.

I recently gave a lecture to some elderly people, and they were so excited to send kisses that some of them opened a Facebook account just to post. They went to the website and started talking to the people who posted photos. At first glance it’s a shallow project, but this element of communication is the project’s depth. It’s important if you love peace, communication, and connection. If you click on any of the photos you can see the comment that was published with that photo.

Tabibian: Those that participate in the project show a different picture of their country. If someone else comes along and wants information, these people are willing to share their perspective.

Who is the hardest audience to get the message through to?

Tabibian: Americans. Iranians can give you names of the past 10 American presidents. They would even know in the most remote places of Iran. If you asked an American to name the last two Iranian presidents, they wouldn’t be able to. Mohammad Khatami was great, but nobody paid any attention to him. Now you’re just stuck with this stereotype.

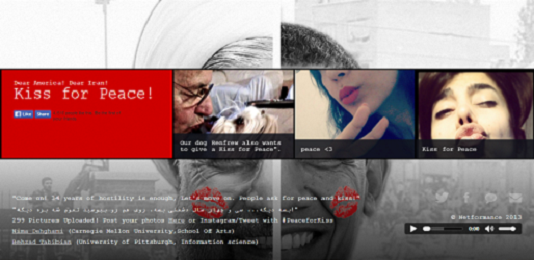

Photo Kiss for Peace Project

What types of receptions have you gotten from Iranians?

Dehghani: Eighty percent of the participants were Iranians; however, some Iranian social and political activists have a problem with this kind of online campaign. Those who criticize this idea have a great distrust in the Iranian government. They think the government is monolithic, something fixed. That’s the opposite opinion held by those who participated in the elections and got results. Critics are always trying to criticize anything that’s related to improvement. They say, “So what? How does this change anything in Iranian affairs, especially domestic affairs?” They want a great change.

Tabibian: Most political experts don’t have an understanding of how human interaction works. They’re living on a different continent with their numbers and threats. They don’t see the first-hand interactions. This kiss idea introduces humanity into a political issue, and creates a closer understanding of opinions.

Dehghani: The kiss is something emotional; it’s human.

Tabibian: Anyone can relate to it.

Did you face any obstacles with the Kiss for Peace Project?

Tabibian: We developed our website on a Google service that’s banned in Iran. We contacted Google to help us fix this, but we didn’t get a response. It was very unfortunate that we had censorship coming from this direction. In Iran, when you try to visit the website you get a message from Google, “This service is prohibited in your country.”

Dehghani: While we have problems with Google, we have censorship on other sites like Facebook and Twitter, too. If these barriers weren’t there, we’d get 1000 kisses in two days.

Photo via Facebook.

How do you, and the Iranians that participated, get around the censorship?

Tabibian: That’s what people do in Iran.

Dehghani: There’re a lot of laws in Iran that restrict people in terms of their clothing, what they do in their home, and what they watch. People find ways to get around these laws, and most people are successful at getting what they want. In the case of the Internet there are a lot of what we call anti-filter services, like VPN. We suspect that the Iranian prime minister is using one of these programs to get on Facebook. For that matter, the president, prime minister, and supreme leader all have Facebook accounts.

Tabibian: It’s part of the irony. These sites are banned, but they’re all there. For example, before the press conference at the recent Geneva talks, Mohammed Zarif, the Foreign Minister of Iran, posted his report on Facebook. By the time the press conference was going on, people were already sharing and posting his status.

Dehghani: I cannot say we don’t have strict censorship in Iran. I have three books that are banned and couldn’t be published. Three or four of my plays are also banned, but instead of performing at the Tehran City Theater I show my plays in underground coffee shops. Iranian people are actively resisting.

How successful do think the Kiss for Peace Project has been?

Tabibian: I’m perfectly happy with what has happened so far. We’re hoping to develop better ideas and presentations. But it’s only two of us. Currently we don’t have any support. We are paying for the domain, hosting—everything. It takes time, effort, it breaks, and people get disappointed. We’re both students, so it’s not like we can spend a full day working on it.

Dehghani: I don’t know the participants, but we appreciate their participation and can’t say this is just our project, because they’re all collaborators. My goal as an artist is to make participatory art that connects people from around the world, but, as a social activist, my goal is peace.

One Comment on "A Kiss in the Right Direction: An Interview with Nima Dehghani and Behzad Tabibian"

Trackbacks for this post