“If I’m Not Speaking That Means I’m Dead”: An Interview with Liao Yiwu

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / January 7, 2014 / 1 Comment

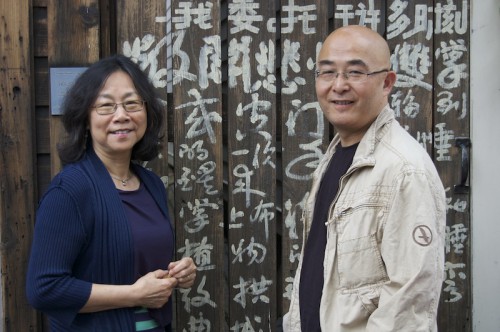

On a warm May day in Pittsburgh in 2013, Liao Yiwu sat down with his long-time friend and colleague Tienchi Martin-Liao. They talked about literature, emigration, and politics. If they had tried to have this conversation in China, it could have been considered illegal.

Liao Yiwu, the writer, poet, and “memory keeper” has been living in Germany since 2011, when he escaped China after being repeatedly banned from leaving the country. In 1990 Liao Yiwu was imprisoned for four years for his poem “Massacre,” which he wrote in response to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests. His experiences in prison became the basis for his book For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison. Liao Yiwu is also the author of The Corpse Walker: Real Life Stories: China From the Bottom Up and God is Red.

Living in Germany, Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, whose members include Liao Yiwu and imprisoned Nobel Peace Prize-winner Liu Xiaobo. She is a writer, researcher, and activist who currently writes “Blind Chess” as a Sampsonia Way columnist. Her close friendship with Liao Yiwu helped him have his work published in Germany.

Tienchi Martin-Liao and Liao Yiwu came to Pittsburgh in May for City of Asylum/Pittsburgh’s Exiled Voices of China and Tibet event. As a part of this event, the two friends sat down to discuss Liao Yiwu’s literary journey from romantic poet to memory-keeper, his physical journey from prison in China to life-in-exile in Germany, and his dreams for China’s future.

Tienchi Martin-Liao: After the Tiananmen Square Massacre happened, there were hundreds of thousands of people who left China, and many of them came to America. What was your situation?

Liao Yiwu: At that time, if I had escaped, I would have gone to America. I made a plan with Liu Xia and some of my friends, who worked on my film Requiem to escape. That was in 1990. Originally I was in Shenzhen, coordinating with a friend of theirs to escort me, but then I was captured at the train station. If I had escaped, I definitely would have gone to America.

After that, how did you get to Europe in 2011? Why did you go to Germany and not America?

It started in 2009, because of the Frankfurt Book Fair, which a lot of people attended because of the incident involving Bei Ling and Dai Qing. At the same time the German translation of my book The Corpse Walker was published. So at the Frankfurt Book Fair my name attracted lots of attention, and 9,000 copies of my book were sold.

Then, in March 2010, the city of Cologne sent me an invitation to their literary festival. I went straight to the German consulate in Chengdu to get in touch with them for visa help. The Chinese police did not approve my visa. Because of this I wrote an open letter to Chancellor Angela Merkel, which was then published in The Sueddeutsche Zeitung. Merkel sent a response through the Asian Human Rights Commission, and they asked me for my reply to Merkel. I sent her a pirated copy of the film Das Leben der Anderen (The Lives of Others).

I wanted to remind Merkel that we Chinese were living under the same circumstances as East Berlin in 1984: A monitored environment with no freedom of movement. After that, things became very theatrical. I received a visa and boarded a plane to Germany at the Chengdu airport. After I had already boarded and fastened my seatbelt, the police took me off the plane. There were more than ten policemen there carrying sub-machine guns, like they were trying to capture an infamous drug lord.

Later on, as this situation became bigger and bigger, the Berlin Literary Festival held a worldwide reading of my works. In the end, when Merkel was talking business, she also talked about my situation. Then, in September 2010, I was finally able to go to Germany for the first time, for six weeks.

While I was there, our friend Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. It was at the Frankfurt Book Fair that I found this out. You, Tienchi, were also there, and we hugged each other.

After Liu Xiaobo won the Peace Prize, his wife Liu Xia was able to visit him in prison, and I thought that China’s situation would improve. My trip was over, and I was getting ready to go back to China. My friend Meng Huang wanted me to stay in Germany, but I refused. I didn’t expect the situation in China to deteriorate so quickly. I didn’t expect that the Jasmine Revolution would happen. After that, things became very tense.

After the Jasmine Revolution, how were you treated by the government?

The government was watching me more strictly. For example, once I went out drinking with the writer Ran Yunfei. The next day Ran Yunfei was arrested, and two policemen came to my house and asked, “Did you know that something has happened to Ran Yunfei?” I said, “If something happened to Ran Yunfei what does that have to do with me?” They said, “Weren’t you drinking with him yesterday?” I said, “Drinking with him doesn’t mean I have anything to do with this.” They said, “Ran Yunfei has been arrested, and you have to stay in your house.” I asked them why they detained Ran Yunfei, and they said that he was involved with the Jasmine Revolution.

Afterwards I found out that Ran Yunfei had received some news about the Jasmine Revolution, so he forwarded it via email. There was a popular phrase that year, the so-called “keyboard crime.” Just for forwarding a post or article you could be locked up. Ran Yunfei was imprisoned for several months. Even though I didn’t commit a “keyboard crime,” I was associated with him and was under house arrest for two weeks. Later, as I was preparing to leave the country, the police asked me to have a talk with them.

They told me I couldn’t publish For a Song and a Hundred Songs in Germany or Taiwan. That book’s manuscripts were confiscated twice. Later I thought about how they knew about the agreement with Fischer Verlag. It must have been because they were monitoring my email that they found out that the book would be published in Taiwan and Germany.

In the beginning I said, “I only have a verbal agreement with the publishing house, there is no formal written contract.”And they said, “You have to sign a guarantee for us that you won’t publish the book.” I looked at the agreement, which had seven requirements on it. and I felt that signing it would hurt my honor. I called you, remember, and told you all this. You said, “Don’t worry, just sign it and try to get out of the country.” Finally on March 28th, 2011 I said, “Ok, I’ll sign it.” One of the policemen said there was a new notice from above. He said, “You are a sensitive case, you definitely can’t leave the country.” I asked when I could leave the country. He said he didn’t know. Just like that. After that, my situation became more and more serious. It lasted until Ai Weiwei was arrested in May.

Just before that I had told Ai Weiwei that I definitely needed to leave. Ai Weiwei said, “Where will you leave from?” I said, “From Beijing.” He said, “We’ve known each other for more than ten years, and I’m advising you to not take the risk this time.” I said, “What risk am I taking?” “Last time we got you on a plane they took you away only for a few hours, and it became such a big news story. This time you’d have to disappear for a long time.” I felt my scalp tingling because there is no rule of law in that country. There was nothing I could do. Originally I was planning to leave the country on April 4. On April 3, Ai Weiwei disappeared at the airport. That was the other popular phrase in China that year, “disappear.” I had many friends who disappeared.

Why were they so afraid of your book For a Song and a Hundred Songs? You published other books before, right? Why were they so unhappy about this book?

This book describes my experience in jail after the Tiananmen massacre. It talks about torture, death sentences, and the experiences of people in Chinese jails. The police said the book was very deceptive.

At that time, I didn’t realize how serious the problem was because the state apparatus is always pushing the red light button to remind you that they’re watching. When the agreement with Fischer Verlag was signed, I thought that this book would definitely be less marketable than The Corpse Walker. There are many different kinds of stories in The Corpse Walker which could attract more readers, and many years had passed since For a Song and a Hundred Songs was written. The reaction of the state apparatus went beyond my expectations because there are so many other people working hard to expose the truth of the prisons.

This book has put China’s government, prison system, and judicial system in a place in history which they did not want. So it was through this process that you arrived in Germany. You were received very warmly in Germany after getting there. They treated you as a hero. Do you think this praise and admiration is related to Germany’s history and culture?

I think it’s very closely related. The first time I went to Germany I saw their culture of commemoration. It was a very big surprise. I visited Moabit prison three times, and each time German people reminded me that this was where the Communist Party Secretary General Erich Honecker was kept while awaiting trial for human rights abuses, and that he had deserved to be imprisoned there. German people’s memories are really good. The fall of the Berlin Wall was in 1989, the same year as the Tiananmen Square Massacre. It has a very close connection with the happenings in China. In the same year China sank to hell, the Berlin Wall was torn down down.

The German philosopher Theodor Adorno said, “Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” I’ve noticed that since you’ve come out of prison, you really haven’t written any poetry. Do you feel that poetry can no longer express your feelings and experiences, and now prefer to write memoirs and reportage?

In 1989 I still had a poetical sense. I liked living a romantic lifestyle, wandering around like Allen Ginsberg, and behaving unusually. I was attracted to anarchism and didn’t participate in any movement. But after going to prison, I saw an aspect of China I had never seen as a poet. When I entered the prison, I couldn’t even speak. There would be a group of people pressing you to the ground, completely stripped, with one foot on your face, shaving your head, and using chopsticks to fuck you in the ass. I couldn’t understand this kind of thing when I was a poet. I didn’t know of these atrocities until they happened. When I was young, I didn’t want to know. They don’t have anything to do with poetry. After experiencing this, as a person whose occupation is related to language, I lost my voice. There is no way to talk about this violence using the language of an intellectual or a poet, and there is no way to convey the grief underneath the violence. You can’t understand the malicious language in the prison, the kind of savagery that exists.

It was the most dark and preposterous side of humanity. In order to adapt to that, whether you want or not, you become a witness. When you’re sleeping between two death row inmates, what kind of a poetic sense can you have? One prisoner is telling you how he cut his wife into pieces. Another is telling you he is going to escape through the sewer. Poetry is something so different from those kinds of people. And little by little I became like them. I was transformed. I became cruel and was involved in fights.

Coming out of prison your body is full of many toxins; for example, a lack of empathy towards others. In the end you will be transformed into that kind of person. At least writing is a way to detox, otherwise the nightmare will follow you. I actually didn’t have any other motives when I started writing about my prison experience. In the beginning it was just a way to detox, a kind of selfish endeavor.

So, your accomplishment and skill, the way you express your emotion, where did you get the inspiration? Is it from classical Chinese literature? Were you influenced by Western literature?

I remember as a young child when my father would put me on a very tall table and make me recite ancient Chinese poetry and essays. I was really young then, three or four years old.

At that time I used to wobble when walking. That lasted one or two years. I couldn’t do it well, and I hated my father. This may be one of the subtle reasons I became a writer. The second is because of all of the Western writing coming to China in the beginning of the 1980s. That was one of the best periods in China. A lot of old translators got back their vitality and began to translate all kinds of things. The third inspiration is the time I spent in jail.

You learned a different kind of language from those lower-class prisoners. Did you get a feeling for the richness of folk language?

The language in the prisons is a special sort of language that is to the point and receives direct responses. Those bottom-level criminals are the most direct. For example, when I was in prison, I heard two people arguing. “You’ve wronged me three times, you owe me a portion of meat.” “I don’t owe you anything.” “I’ll ask you again whether you owe me anything.” This prisoner asked the other three times while his eyes were on the roof to check for guards; suddenly he attacked his opponent so hard that the other guy couldn’t speak. Then he shouted to the guard: “Report! This guy has a stomach ache, can I bring him to the restroom?” He got permission, and he carried the guy away and whispered, “Fuck, you still dare deny the debt?”

After you got out, you said that you were a “memory keeper,” a recording device for this age. Do you think that the things that happened in the last sixty years in China, the many different political movements—the Cultural Revolution, the opening up of the 1980s, the forward movement of the 1990’s–could only have happened because of traditional Chinese culture?

I don’t think it is related because the first thing the CCP did was to cut off traditional culture. There is an ancient saying that the emperor cannot manage so many people. Traditionally each village would choose a leader and safeguard itself. Although China looked like a unified whole, there were many independent units. Small governance is a Chinese tradition. The CCP has broken this tradition, cut it off. They started the turmoil of revolution and subverted tradition. Mao Zedong began the revolutionary experiment and initiated one political movement after another. He caused the death of at least 100 million people throughout this process. I think this is indicative of a dictatorship: It allows neither autonomy on the local level nor traditional culture. Whether you look at Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, or the current leadership, there is no traditional culture.

Why do the Chinese people continuously accept and deal with this?

This is like what was written about in George Orwell’s 1984, the extinction of emotion. I think Orwell is the greatest writer from the last century. The CCP went step-by-step and finally nothing was left but Mao’s bible. All the people are denunciators. Hitler eliminated people, but Mao Zedong transformed them. In terms of traditional culture we have a profound heritage which is the opposite of communism. For example, the Confucian philosopher Mengzi said, “The people are the most important element in a state, next are the gods of land and grain, least is the ruler himself.” These traditions, as well as the traditions of Laozi and Zhuangzi are getting lost nowadays.

I think after World War II Germany reflected on the crimes it committed. Since the CCP’s rise to power, some Chinese people have become perpetrators and have not reflected on this history. What is the reason for this? Is it because the government doesn’t allow it, or is it because the people lack a spirit of repentance?

I think it’s the tyranny. I think that tyranny is the root of all evil. They have control over all of the country’s resources, including the resource of education. Look at Tiananmen: Yesterday I met a girl born in 1987, and she asked me, “What was that situation in 1989 about?” I just looked at her and asked, “Didn’t your father tell you about it?” She said that her father never told her and that he hoped that her generation would be happy and didn’t want to talk to her about all this serious stuff. However, the resources for tyranny, like Aung San Suu Kyi said, are based on the fear of the people. After a while the terror becomes subconscious.

Maybe this girl’s father thinks that this tyranny is bad, and that Western democracy is good. But he is terrified. Look at the Jasmine Revolution: They arrested so many people, who wouldn’t be afraid? Look at Tiananmen: There were more than 200,000 soldiers. Before that I didn’t know what fear was. When I was young my dad told me, “You have no idea how powerful the CCP is.” I did not believe him, and I thought I was brave. But after the massacre happened, and I saw that they could kill two or three thousand people under the West’s nose, I realized, “What could I ever do?”

The success of their tyranny is that they can say to the West, “After killing our own citizens, our nation is still strong, we can do business with you. You should forget what happened like we have.” The uniqueness of their tyranny is based first upon fear, secondly on money. They control the weak points of humanity. It’s the most evil kind of regime, not built on any kind of values, but on the weaknesses of people.

Some say, “Exiles lose the ground but gain the sky.” But looking at the past, many exiles, after leaving their homelands, are no longer able to write. Do you feel that after coming to the West, even though Western society has accepted you, that you have lost something? Has this affected your writing?

I think I can still write. When I was in China, I had a kind of fantasy regarding the West. I thought that the West would have a clear set of values, an idea which my friends had conveyed to me. When I was depressed, Liu Xiaobo tried to encourage me by telling me about the West. But when I got to the West, I saw some things I could not accept. For example, Western sinologists unexpectedly speak up for the CCP. It’s obviously because they can benefit from it, and they give all kinds of excuses for it. Politicians talk about the Tiananmen Square Massacre, saying that not that many people died and that there were some benefits to the economy. Even Harvard has become like the Huangpu Military Academy for training the CCP’s bureaucrats.

There are also some really prominent Harvard scholars defending China’s recent history, like Ezra Vogel and his book Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China.

Why is there this double standard? Weren’t Chinese exiles coming to the United States because of democracy and human rights? These human rights activists speak out against Stalin and Hitler. Isn’t Mao Zedong just as bad as them? Isn’t Deng Xiaoping just as bad as them? I had thought that this was very clear, but after leaving China I started to think it wasn’t clear at all. I remember finding out that Mo Yan had won the Nobel Prize for Literature. It was then that I saw how confused Western values were. So, currently I have some recognition in the West, and I have to constantly write and give speeches because if I don’t talk about this stuff maybe I will become confused myself. Tyranny might become accepted. China is the world’s biggest trash dump: From human emotion to the natural environment, it’s been badly polluted. Yet there are still people singing its praises. This is something I cannot accept, even though some friends say that my behavior is a little over-the-top. However, if I am not speaking that means I am dead. Now I have the opportunity and the power to speak, so I will speak.

In the past, the West hosted so many exiles. Now, it hosts so many corrupted government officers and wealthy people. What’s happening to our world? Can profit swallow human values? So we are in an era of confused values. A crisis-filled era. This kind of situation, for a writer with a public platform, is a huge challenge.

Talking about the West, usually as Chinese people we think of the United States as a capitalist and ruthless society but we forget how it can help exiled Chinese. What do you think of this?

I still remember when the June 4th massacre happened in Tiananmen Square. The American government came forward right at the beginning to take a stand against the Chinese government. At that time, to be honest, all Chinese people were really grateful to the American people for accepting so many exiles.

At that time I was in contact with many exiles, and they thought that after two or three years they could return to China. But year after year, they were still unable to go back, and some have since died in exile in the United States.

America gave some exiles the quiet atmosphere they wanted. Kang Zhengguo, a Chinese academic, said that it was in the United States that he found the ancient Chinese atmosphere he was looking for. This is not what anyone would expect, but in the beginning, who ever thought they’d be in exile? In the end, exile was forced upon us.

You came to the United States in the fall of 2011, for a two-month visit because of your book God is Red, a book about Christianity in China. You interacted with American scholars, like Ezra Vogel, and you also spent some time with Chinese-American Christian congregations. I’d like to ask you to talk a little bit about your views on that visit.

I think that part of the United States has a very clear set of values, or else we wouldn’t be sitting here talking today. And there wouldn’t be activities like my reading with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh today and my engagement next week at the New York Public Library. I’ve seen many political intellectuals who are fighting for universal values. They have passionate discussions over long periods of time and have changed a lot of things. I appreciate that. However last year, when I was in New York City, I saw a billboard advertisement for the Xinhua News Agency in Times Square, and I was just dumbfounded. The Xinhua News Agency is clearly a spy agency. I told literary agent Peter Bernstein and writer Wen Huang my feelings, and they said, “This is a free society; they have money, so they can put up an ad. Just because they have an ad there doesn’t mean people will think they are good.”

Rich Chinese people?

Both rich and poor Chinese people went to the churches. It seemed like all sorts of people are mingled in the embrace of God. This was a pretty interesting phenomenon. And then, my experience at Harvard was pretty strange. At Harvard I gave a lecture and read my poem, “Massacre.” After I read my poem, nine professors invited me to a meal. In the beginning I felt a little timid. I, a Sichuan rat, had never eaten with so many professors. Finally they got to discussing whether they would put the video of me reading “Massacre” on Harvard’s website. Those professors started discussing it right in front of me, and they decided to not put “Massacre” on the website. I later heard gossip that this would negatively influence their relations with China, but the reason they gave me publicly was that they were afraid of the negative impact on my interpreter. I’ve had many interpreters around the world, and there’s never been someone who got trouble just for being my interpreter. I remember thinking, “Isn’t putting my video on your website a simple thing? All of the lecturers that come are all put on the website. Why can’t I be?” That situation hardened me.

Of course I also met people whom I respect a lot, like Philip Gourevitch and Salman Rushdie, and at key moments both have stood up in support of me. So that is really encouraging. You can feel their support of Chinese dissidents. But in general my impression is that if an established organization, for example, Harvard or the Nobel Prize Committee, with many years of heritage doesn’t change, they can become corrupt.

All politicians have dreams; for example, Xi Jinping and his so-called “Chinese Dream.” Do you have a dream? What do you look forward to, or hope for, both for yourself and for society?

This is what I talked about when I won the Peace Prize at the Frankfurt Book Fair last October. My dream is that the empire breaks apart into ten to twenty small countries. When that happens, I can return to the country of Sichuan and never return to China. Then, if you guys want to have a dictatorship in Beijing, you can have it. Sichuan can choose its own leader, and that land would really be ours. But right now it belongs to the CCP. Starting over, that is my dream.

One Comment on "“If I’m Not Speaking That Means I’m Dead”: An Interview with Liao Yiwu"

Trackbacks for this post