Seeking Accountability for Abu Ghraib: An Interview with Katherine Gallagher of the Center for Constitutional Rights

by Caitlyn Christensen / April 16, 2015 / No comments

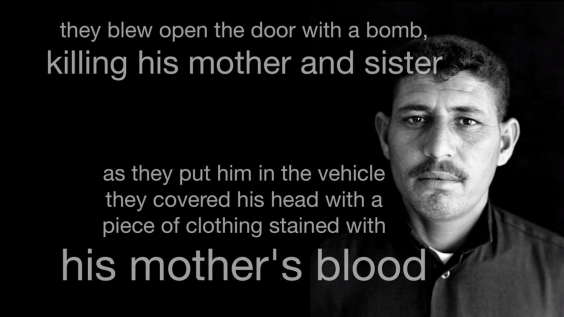

A former Abu Ghraib detainee photographed by Chris Bartlett for The Detainee Project. Photo via YouTube user: Center for Constitutional Rights.

Since 2004, attorney Katherine Gallagher, her colleagues at the Center for Constitutional Rights, and the Iraqi plaintiffs they represent have been seeking to hold the US corporations who profited from the tortures at Abu Ghraib accountable. Salah Hassan, an Al Jazeera media worker who was detained and tortured at the prison, is one of the plaintiffs in Al Shimari v CACI, the lawsuit brought against military contractor CACI. Sampsonia Way interviewed Ms. Gallagher about the case and the precedent it sets for human rights litigation in the United States.

How did the Center for Constitutional Rights first become involved in bringing the case against these contractors?

The first plaintiff in the case, Mr. Haidar Saleh, had been detained at Abu Ghraib under Saddam Hussein in the 1980s. He fled Iraq and was living in Sweden in 2003, at the time of the US invasion. When the US put out a call for Iraqis to help rebuild their country, Mr. Saleh left Sweden and returned to Iraq. Soon after he arrived, he was stopped at a checkpoint by US officials, arrested, blindfolded, and put in detention. Eventually, he found himself back in the same Abu Ghraib prison where he had been tortured during Saddam Hussein’s regime.

While at Abu Ghraib, Mr. Saleh told his captors that he was a Swedish citizen. Despite that, he was tortured, and subjected to sexual assault. He was released in January of 2004.

Mr. Saleh had family living in Michigan, and he came to the United States to see his family soon after his release. When he told them what had happened in Abu Ghraib, they initially thought that he was having flashbacks to what happened to him under Saddam Hussein. He insisted that he was telling them what had happened to him under the Americans.

This was before the Taguba Report was leaked, and before the publication of those horrific photos. Mr. Saleh’s family put him in touch with a lawyer, Shereef Akeel, who brought the case to the CCR. Mr. Saleh told Shereef that he was far from the only Iraqi wrongfully imprisoned and tortured at Abu Ghraib, and if he came with him to Iraq he would introduce him to others. Shereef travelled with Mr. Saleh to Iraq in the spring of 2004, and some of our initial plaintiffs came from that trip.

Over the years, the litigation went on, and detainees were released and began to talk to others about what they had experienced. As more learned of our litigation, the numbers grew. We’ve now represented almost 340 detainees through these lawsuits. By the time Salah Hassan came to us, our team in these cases was well known through word of mouth.

In 2004, The Nation profiled one of your plaintiffs, Al Jazeera media worker Salah Hassan. The profile included statements by Hassan that he was harassed at Abu Ghraib and called mocking names, like “Al Jazeera” and “boy.” But Hassan’s case has gone largely unreported by the mainstream media, despite the US’s proud history of press freedom. Why do you think Hassan’s case did not receive more media attention?

Last year, Salah Hassan received some coverage with the ten-year anniversary of the release of the Abu Ghraib photos. He was interviewed on BBC’s Witness and appeared on Democracy Now!

I can’t answer why there hasn’t been more media coverage, but I think in general – whether in Iraq or Afghanistan, or elsewhere – there has been a lot of silence around the victims, their human stories. In some ways, that is because of the distance and the challenges of meeting plaintiffs. We helped a German journalist travel to Iraq and meet some of our plaintiffs. We would have facilitated an American journalist undertaking a similar trip but we didn’t have such a request.

However, in 2006 or 2007, artists Daniel Heyman and Chris Bartlett contacted us wondering how they could help bring their skills to bear on the issue. Chris Bartlett travelled to where we were interviewing plaintiffs and took portraits of the people who had previously only been known through the naked and hooded notorious photographs as a part of the Detainee Project. His photos are incredibly dignified and are presented with snippets of the Iraqis’ stories. Daniel came with us on multiple trips and did watercolor sketches of the plaintiffs and presented them with some of their own words to give them the opportunity to tell the story to an American public.

Besides the German story you mention, has there been any coverage of this case in Iraq or in other countries? Has your case been used for political means in Iraq?

I can’t say that there hasn’t been any coverage, but I will say that is not necessarily an easy thing to be a plaintiff living in Iraq. After representing a number of Iraqi plaintiffs, I can say that people do not necessarily understand that they haven’t gotten rich just because they filed a case. There is a lot of stigma that comes with being detained, because there were so many people arrested during the occupation and fear that being associated with someone who was arrested might lead to your arrest. With what’s going on in Iraq now, there is still a lot of basis for suspicion. Detention at Abu Ghraib is not something that people are necessarily speaking about.

Does the popular narrative of the events that occurred at Abu Ghraib – for example, the story that Charles Graner and other personnel involved were a “few bad apples” – factor into your case in court?

Military reports have found that there was a command vacuum at Abu Ghraib. In that vacuum, contractors worked with military police to carry out acts of torture against Iraqi detainees. We allege contractors participated in the abuses, and certain of them were ringleaders in the conspiracy to seriously mistreat Iraqi detainees.

We’ve read that Abu Ghraib prisoners were forced to sign waivers, upon their release, in which they gave up their right to bring a lawsuit against the US government over their treatment in the prison. Did any of your clients have to sign such a waiver? What more could you tell us about this practice?

What’s important to note is that this case is not being brought against the US government simply because that could be a challenging legal case – we’re bringing it against for-profit contractors who were identified in early reports about Abu Ghraib and through testimony as being involved in the serious mistreatment of detainees. Some CACI employees were identified as ringleaders engaged in the alleged military conspiracy. This is a piece of the accountability puzzle that all of us, the CCR and our plaintiffs, felt was an important one to pursue.

These companies made a lot of money in Iraq, and some continue to make a lot as contractors with the US government. Some of the reasons why we go to war are implicated in this case.

Your plaintiffs were jailed over a decade ago, and their case (in one form or another) has been pending in the courts since 2004. How has the drawn-out nature of this case affected the plaintiffs?

Torture is a crime that inflicts severe physical and mental harm. The plaintiffs endured physical suffering while detained, but the mental harm is ongoing. They might go through periods when they are trying to forget what happened to them and can go about daily life. When we have long, drawn out litigation, and we have to meet with our plaintiffs after a period of time, and go back through detail of this horrific experience, it brings them back to a decade ago.

They haven’t gotten over it. They have nightmares and their daily lives are impacted in other ways, but it all becomes even more extreme when suddenly we are back, talking about the case again. Nevertheless, all of them have remained committed to seeing this case through.

What would meaningful accountability for Abu Ghraib look like? Can what happened to your plaintiffs ever be reconciled?

We seek a trial because it would be very good for our plaintiffs’ individual stories to be heard by an American jury, and to understand who some of the actors were in Abu Ghraib. Charles Graner and Lynndie England are names that are known. I’m not sure that as many people know the role that we allege that CACI played, even though they were identified in US military reports. For the victims, it could bring some closure and some measure of justice, even though it can’t undo what happened.

What precedent does this case set for others who are seeking accountability for human rights violations in the US courts?

In 2013, in Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, the Supreme Court opined on the Alien Tort Statute, a very short but important law from 1789. This law says that non-US citizens can bring a claim in U.S. federal courts for a violation of a law of nation. Acts like torture, genocide, war crimes, are recognized as violation of the law of nations, or customary international law. In 1979, the CCR resurrected this law and began using it for human rights litigation, and human rights litigation has used this law since then. In Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, the US Supreme Court found non-US citizens bringing a human rights case into US courts need to have the case “touch and concern” the US.

Initially after Kiobel, the district court dismissed Al Shimari v. CACI, and said that the case didn’t “touch and concern” the US because the torture occurred in Iraq. We appealed and numerous amicus briefs, or friends of the court briefs, were filed in support of our case. We laid out numerous arguments for why our case concerned the US, starting with the fact that CACI is a US corporation working under contract with the US government. We alleged that they conspired with members of the US military, who were court martialed under US military law, and their acts of torture took place in a US-run facility in US occupied Iraq. Everyone from the former President of the United States to the military to Congress had condemned and investigated what went on at Abu Ghraib.

We also said that the US was one of the primary drafters of the Convention Against Torture, and has committed itself to eradicating torture. Part of eradicating torture involves punishing torturers and providing redress to torture victims.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated our case on June 30, 2014 and listed five factors as to why our case did involve the United States. From a legal perspective, that is a very good decision for human rights cases and can be invoked by others. And more than the legal precedent, it is an important reminder that the Alien Tort Statute was intended for non-US citizens, like our plaintiffs, to be able to seek redress for human rights violations under US law, particularly those involving U.S. citizens.

On February 6, Al Shimari v. CACI returned to the district court once again, and the judge heard arguments over the political question (whether or not the court can hear the case). Can you comment on how the arguments went?

The judge did not make a ruling from the bench, so we do not have a decision yet. The judge heard arguments from both sides and came well prepared. We’re hopeful that we will have a positive decision and that this case can proceed.

This interview was conducted on February 10, 2015.