Servitude

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / April 1, 2014 / No comments

A common mentality in China and India.

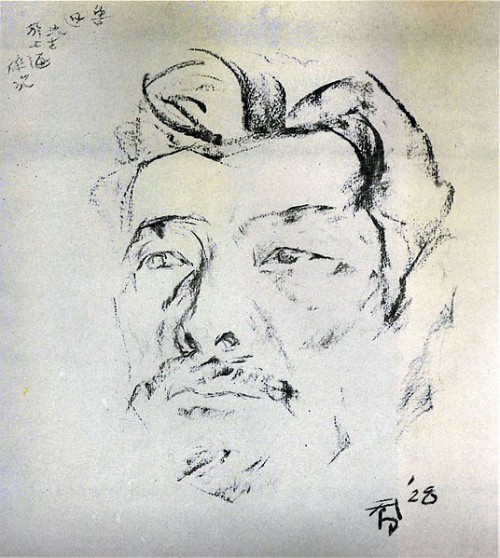

Portrait of Chinese author Lu Xun, by Situ Qiao (1928). Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The great writer Lu Xun (1881-1936) has written many essays about the Chinese national character of nuxing (servitude). In particular, his essays “The True Story of Ah Q,” “Kongyiji,” and “Medicine” expose the philosophy of the common Chinese: “Miserable living is better than good death.” This philosophy is also highlighted in Xun’s famous quote, “It’s extremely easy to become a slave; after that, we are even very much pleased.”

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

Throughout history, the Chinese people have believed in servitude. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, there were some occupied areas where only a handful of Japanese soldiers were present. The invaders could quietly carry out the massacre of tens of thousands of Chinese civilians without issue because the people would obediently line up like sheep to be shot or beheaded.

During China’s three years of famine from 1959-1962, 36 million people starved. According to Yang Jishen, the author of Tombstone, even though some villages were completely wiped out from starvation, there were seldom records about hungry villagers storming the official granary. Even in the period of famine, the Chinese government maintained the appearance of a brotherly state by offering to help to deliver food to African countries.

Since the May Fourth Movement, Chinese intellectuals keep asking the same questions: What is the origin of servitude? Is it rooted in cultural tradition and the imperial system? Could Mr. Science and Mr. Democracy save the ancient nation? It seems that today, the questions remain unanswered.

Indian author Aravind Adiga’s book The White Tiger, which won the 2008 Booker prize and was translated into Chinese in 2010, resonated deeply with many Chinese readers. They feel that reading the book is like looking into a mirror. In the novel, Balram Halwai, the protagonist, writes to the Chinese prime minister Wen Jiabao, narrating his own history of struggle from a lowest Caste Sudras-chauffeur to an entrepreneur. In a witty and sarcastic tone, the author recounts the humiliated, undignified life of poor young Balram, first as a teashop boy, and later as servant and chauffeur for a landlord and his wife. Using the same methods that he was confronted with—corruption, cheating, insults, robbery, murder, and betrayal—Balram achieved his own success as the boss of a call center. In the process of becoming an entrepreneur, he discards his innocence and sells his conscience and soul.

This isn’t the first time a character like Balram has been created. In 1936, Lao She wrote a Chinese Balram in his novel Rickshaw Boy (or Camel Xiangzi). In this novel, the protagonist, Xiangzi, struggles at the bottom of society as an honest, hardworking young man until he ultimately degenerates into undignified scum. The difference between the Indian hero Balram and the Chinese character Xiangzi, is that Xiangzi does not climb to the upper caste as an entrepreneur, but instead sinks even lower as a vagrant. Tragically and cynically, Lao She was ultimately a victim of the Cultural Revolution. Under the communist regime he had to end his own life. After being beaten and insulted by the Red Guards, Lao She drowned himself in a lake in Beijing, clutching Mao Zedong’s works in his arm. He died not a writer of conscience, but a confused and troubled soul.

Today the young writer Adiga should not expect Balram to inspire Prime Minister Wen Jiabao; in China there are millions like Balram who achieve wealth and position, and lose their character and soul. Adiga uses his novel to voice his strong critiques against Indian culture, the Caste system, religion, and the absence of morals and courage—all of which leads to servitude. Similar critiques can be found in the works of Chinese writers like Yan Lianke, Liao Yiwu, Ye Fu, and Yu Hua. However, their cultural critiques are often camouflaged in a skillful cover-up. Different from their Indian colleagues, these Chinese writers are convinced that the characteristics of mainstream Chinese society—extreme utilitarianism and materialism—accelerate the degeneration of morality and ethics, destroy relationships, and evaporate social responsibility. All these ascribe to the frantic fear of the ruling class; loss of power means their miserable end.

Mao Zedong said, religion is the opiate of the people. But today, money is opium for the Chinese. Addiction to opium or money can disarm people; a harmonious society can be achieved as the new boss Xi Jinping trumpets on. Now China wants to export the “opium” to its not so favorable neighbor, India. Specifically, 300 billion dollars to help modernize its infrastructure, build new highways, bridges, harbors, airports, and telecommunications networks.

What an attractive perspective! Yet India is skeptical about this kind of developmental aid. One hundred and fifty years ago, Britain delivered opium to China through the British East India Company and accelerated the decline of the ancient empire. But they also awoke the people, and now it’s a question of whether or not China want to exact its revenge with another form of opium. India has not taken the offer at the moment, but the bait is enchanting.