When Faced with Absolute Truth, Abstain

by Israel Centeno / May 21, 2014 / No comments

Removing the veils of romanticism, idealization, and prejudice from history.

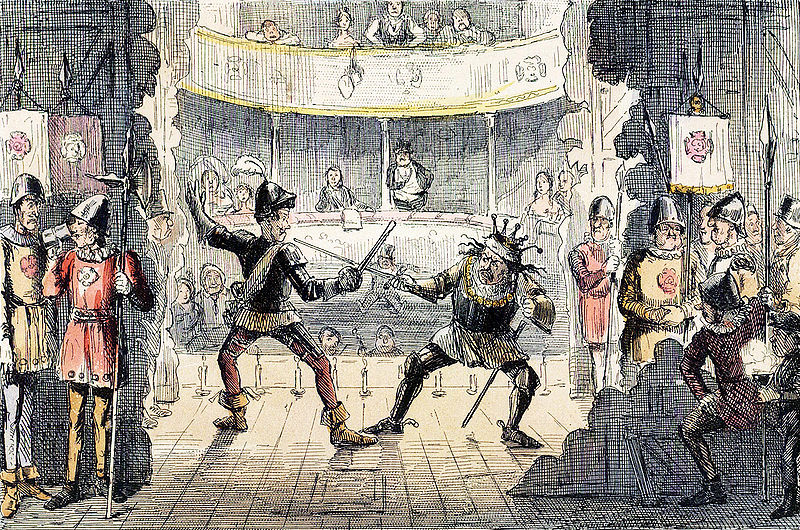

The Battle of Bosworth Field - A Scene from the Great Drama of History: John Leech's illustration of Gilbert Abbott À'Beckett's parodical criticism of the Victorian attitude towards history. Photo: Wikimedia.

The study of history creates many emotional bonds; at least, that’s what’s happened in my case.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

To start with, I was introduced to the history of humanity and my own country as a continuous movement from savagery towards the most evolved states of civilization. It was to consist of unyielding processes of reinventing society, as if an ascending line could be drawn from the dark ages until the present day, almost always with a happy ending for the human adventure. It is doubtless a romantic vision that has been greatly manipulated by the bearers, and usurpers, of power: All those who stand against “barbarity.”

On one hand, we follow the pages of history books, which contain the upheavals of multitudes of people, a seething and unsatisfied force, a sea of lava, the ground itself on the move; on the other hand, we follow the lives of those individuals who, in spite of their mortality, rise up as leaders in order to shape these brute forces of the universe, the torrents that flow haphazardly towards the future. Until the aforementioned line resembles the progression of Beethoven’s Eroica.

These approaches to history, seen in perspective, are startling. Nevertheless, they help to explain both the great catastrophes of the last century and those that are taking place in the current one.

The twentieth century was the century of mass movement, enlightened leadership, willpower, and brute force. Fascism, communism, redemptive movements, genocide, religious messianism, the brute forces of the market, the brute forces of leaders ruling their party and society with an iron fist.

Today, when faced with the events in Venezuela, trying to understand its chaotic reality is overwhelming. Aren’t the idealized, irreconcilable mobs here today acting out of control, mangy and foul-smelling as they establish a dialectic of violent confrontations in a dead-end street?

Though years have gone by and we have left the twentieth century behind, putting distance between us and romanticism, the idealization of mobs, and individual willpower, I tremble with fear, suspicion, and anxiety. The symphonies and marches are out of tune and give me nightmares.

It is terrifying.

On one side, there are mobs with pitchforks and torches, a woman with her breasts exposed, and the forces of nature hungry for the future while demanding heads on spikes. On the other side, there is man, the person who performs and leads, who indicts those wild forces by imposing his rule of steel: A mold, a precise and exact form, an impenetrable corset. A chastity belt.

The history of humankind must be interpreted without any idealization or prejudice. In our mythologizing of the multitudes and the leaders, and our acceptance of the enlightened vanguards who make use of absolute truth to establish order, happiness, and peace, we have been led to quicksand, to traps where we have to pay a high price to escape from the caves and their laws.

Simple premises, the reason behind their failure, could bring us back to a time of good judgment. When faced with absolute truth, we must doubt. The forces of nature seem beautiful when considered from a distance and are, in any case, unlikely nightmares. Peace and tolerance are more likely if they come from a secular dynamic that promotes control. When faced with irrational forces and absolute truth, we must promote diversity and counterweights.