El Ratón: In Memory of Cheo Feliciano

by Israel Centeno / May 8, 2014 / No comments

“De cualquier malla sale un ratón, oye, de cualquier malla” (a mouse will escape from any cage)

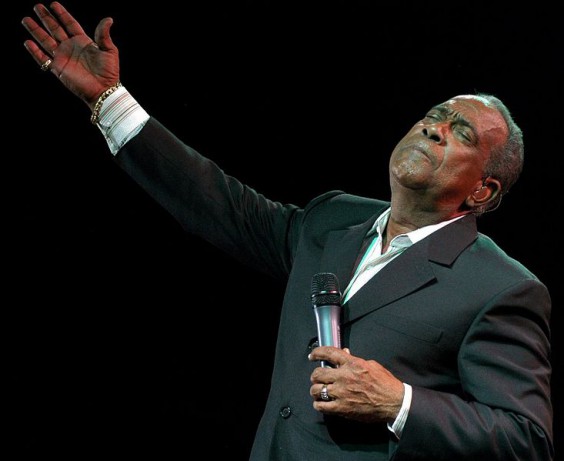

Cheo Feliciano (July 3, 1935 – April 17, 2014); Puerto Rican composer and singer of salsa and bolero music. Photo: Wikimedia.

When I attended the Festival de la Palabra (Festival of the Word) in San Juan, Puerto Rico, I spent a great deal of time wandering about between the La Perla district and the Santa María Magdalena de Pazzis cemetery, located at the foot of the walls of Fort San Felipe del Morro.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

Although I wasn’t looking to gather my memories, the light, strengthened by the sun’s glare on the peaks of the waves, transmuted the lime on Tite Curet Alonso’s tomb into a magnificent white gold.

I insisted upon paying the great musician a visit. And with this simple action I returned to my childhood in Venezuela, even though I ‘d set off with a definite purpose.

There was more to the Caracas districts of Marín and La Charneca than what was depicted in that infamous photo from Rómulo Betancourt’s time, in which guerrillas brandish submachine guns in the frame of a Ford advertisement. There was more to them than the familiar, turbulent world struggling with political violence, and more to them than the conservative, Catholic setting of a poor-yet-rising middle class. I grew up among the pasajes of San Agustín, a poor neighborhood in the center of Caracas. Pasaje Two was a little ways away from the Marín district and the urban guerrillas hidden under the stairs. Alongside shots fired during a chance encounter and dogs barking on the flat roofs—and other background noises too, like the raids being carried out in search of Coquito, the sole troublemaker of Pasaje Three; the brawls in the Blanco pool hall; the police receiving favors from Castelia the prostitute during their rounds, visiting her pink house—you could also hear strains of a trumpet solo and the voices of soneros coming from the mountains.

The people of Marín danced salsa, and when Tite Curet or Cheo Feliciano came through Caracas, they went up to the mountains, singing and playing their instruments, and smoking their malanga cigars. They became the sounds of the night that weaved in and out of La Ceiba, El Manguito, and El Mamón, among the pasajes and La Ruiz Pineda. With their playing and singing they won out against any unfulfilled desire, misfortune, or ambition; they were the music with its, with their, tragic burden: A sound that dulled the senses and gave relief from despair.

Many years prior to this memory driven on by mourning, I wrote about my nostalgia for the music by Grupo Folklorico Y Experimental Nuevayorkino, or maybe I wrote about my nostalgia for the creation of songs about anger. This is probably my first memory of New York, many years before I visited New York for the first time.

The game began by searching for Se te olvidó que te olvidé, a reference to the experimental band and the theme.

I knew nothing about them that I hadn’t learned at easily forgotten parties, or, rather, I knew very little, typical of someone who listened to Radio Aeropuerto at the end of the seventies. However, during my time in San Agustín, I met the great Chuy Quintero, the best Caraquenian percussionist of the time, through whom I came to learn certain Latin rhythms. He told me that not everything was salsa: In the beginning, there was saoco, guaracha, and guaguancó. Guaguancó. Cheo. The first port of call in understanding the Latin rhythm. Afterwards, everything was a mess, total confusion. People danced incompetently to this kind of underground Latin rhythm, shared by a community who would echo Cheo Feliciano in Hornos de Cal or Marín. They stuck to their moves; none of this ballroom dancing. They danced to the sound and the soneros. There was more to Cheo than just El Gato and La Fania; he sang other unusual melodies. During that time, I rid myself of all disappointment and “enjoyed” the anger of the first great scuffles to those rhythms, always carrying the poem “Derrota” by Rafael Cadenas in a jacket pocket and ending up falling dizzily upon the clean sand of a beach in Aragua, or upon my friend’s gigantic bed in her penthouse in Las Lomas de Urdaneta. And time went by.

I shed my skin and was devoured by a panther.