The Communist Party of China’s “Mother Beats Child” Syndrome

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / November 23, 2015 / No comments

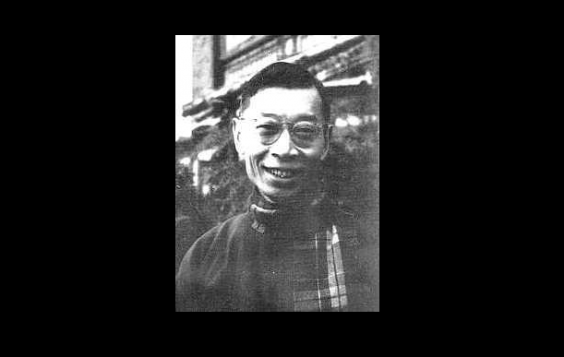

Chinese intellectual Fu Lei. Image via: Wikimedia Commons.

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, intellectuals committed suicide in defiance of Mao Zedong’s policies, which would take the lives of millions more.

I fell in love with classical music in my adolescence; Beethoven was one of my favorites. Then one day I came across Romain Rolland’s novel Jean-Christophe, and the protagonist Jean-Christophe Krafft, a wonderful characterization of Beethoven, became my idol. I was deeply impressed by this idealistic and passionate musician, and in my naïve mind, I believed that this kind of noble artist could change our world. My literature-enchanted spirit did help me escape from the ordinary daily routine.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison til 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners, and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

At that time, I did not notice the translator of the great novel. In the 1960s in Taiwan, lots of books and translations were published either anonymously or with pseudonyms, because the authors were in the Chinese mainland. That is to say, they were “Communists,” or at least they were in “bandit area,” a term in Nationalist Taiwan to describe “Red China.”

Many years later, when I went abroad and settled down in Europe, I discovered the Chinese-language translator of Jean-Christophe: Fu Lei. He translated many of the beloved French literature I read, including Balzac’s Father Goriot and Voltaire’s Candide. I found out that this great translator and art critic committed suicide with his wife on September 3, 1966, during the Cultural Revolution. Fu, a proud man, and fan of Romain Rolland, had been publicly insulted and tortured by the Red Guards. The “revolutionary little generals” forced him to kneel, kicked and beat him, and called him “counter-revolutionary” and a “running dog of the Western imperialist.” This was due in part to his son, Fu Cong, a pianist who was sent by the Chinese government to Poland to study, but fled socialist Poland to London. This became his father Fu Lei’s crime as well, with the revolting youngsters labeling him a traitor. After four days and three nights of humiliation and torture, Fu and his wife Zhu Meifu hanged themselves in their Shanghai home. In the letter he left behind, Fu asked his brother-in-law to pay their outstanding balances from Fu’s savings, to give some money to their servant, and the remaining of the 53.3 yuan was enough for the crematory. The letter contained no hatred and no complaints.

On the same night, 800 miles away from Fu, the archaeologist, oracle bones scholar, and poet Chen Mengjia (1911-1966) hanged himself for the same reason: to defy humiliation and groundless political persecution.

There were several artist and scholar couples who committed suicide around the same time: the conductor Yang Jiaren (1912-1966) and his wife Cheng Zhuoru killed themselves with gas on September 6, 1966; literature professor Liu Shousong (1912-1969) and his wife Zhang Jifang hanged themselves in 1969; photographer Chen Zhengqing and wife He Hui took an overdose of sleeping pills on August 27, 1966; at Beijing University alone, there were 24 suicide cases at the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, and more then a dozen in Shanghai.

Some died with their families: pianist Gu Shengying, with her mother and brother; chemist Xiao Guangyan, with his wife and daughter; author Wu Han, with his wife and daughter.

The complete list of the dead is too long to be placed here. It was Mao Zedong’s crazy idea to launch the Cultural Revolution with fanatic teenagers. In the 1980s, the Research Institute of Party History of the Central Committee of the CCP spent two years and seven months comprehensively investigating and verifying a book: Facts of the Political Campaigns since the Founding of the Republic. This book contains shocking records of the Cultural Revolution: “4.2 million jailed for investigation; 1.72 million died of unnatural death; 135,000 counter-revolutionaries sentenced to death; 237,000 killed in armed fight; 7.03 million injured; 70,000 families eliminated. ” According to the oral report of Marshal Ye Jianying, one of the founding fathers of the People’s Republic, at a Central Committee meeting on September 12, 1982, the casualties were actually even higher.

The whole legal apparatus was shut down, and we do not know which authority sentenced people to death. Probably the “revolutionary mass” with the Red Guards as its leaders was the judge. The term “ten years of catastrophe” is widely used in China for the Cultural Revolution, regarded as the darkest episode in modern Chinese history. Yet as soon as the official account touches this topic, the language becomes stiff and ambiguous. With so many victims in a peaceful time, who were the perpetrators? It’s true that the Red Guards carried out the most heinous crimes, but who gave them the green light to destroy? Mao Zedong was the key person, the one who opened Pandora’s box and let out the youngsters to smash the existing apparatus of power in the whole country. Even 39 years after his death, Mao is still the deathly hallow of the Party, his mausoleum occupying the heart of Beijing. His ghost lingers in the minds of the Chinese rulers, who can still use this mummy to scare the people. Neither the Party nor the dead chairman take responsibility for the human catastrophe. Now Xi Jinping’s government takes the same stance as his predecessor. Close the eyes to the ungraceful past; instead, move forward and ignite people’s hope with a glorious “Chinese dream.”

The official tone is not to mourn for the past, after all, most of the dead “counter-revolutionaries” have been “rehabilitated” through the Party, and they have regained their reputation. The famous writer Wang Meng invented a theory to help the CCP out from the embarrassing dilemma. He said, “the Party is like a mother: the mother might beat the child wrongly, but the child shall never blame or hate his mother.”

With this cynical sophistication, Wang Meng, the once “rightist” writer, could win back the government’s trust. He later became Minister of Culture under Deng Xiaoping. Like Wang Meng, many victims have made peace with the perpetrators and are compensated with position and benefit. Even the son of Fu Lei returned to China ten years after his parents’ death. He was “forgiven” for his traitorous deed and was allowed to hold a concert in China, later securing a teaching position in the university. This kind of Chinese “harmony” has been propagated throughout the Hu Jintao era, and now has been taken over by Xi. In the name of “law,” anyone who disturbs the harmony will be punished or put into jail.

After decades of indoctrination, the Chinese are affected with Stockholm syndrome; kneeling down in front of their torturer seems more comfortable then being put in jail. Fortunately there are also people who choose the opposite, Liu Xiaobo, Xu Zhiyong, Pu Zhiqiang, and many others.