Between Black and Yellow is Grey

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / July 13, 2015 / No comments

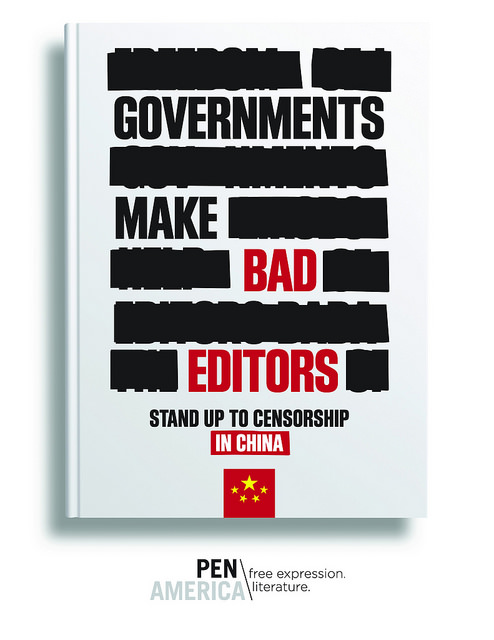

Censorship of foreign literature in China

PEN America released the report, “Censorship and Conscience: Foreign Authors and the Challenge of Chinese Censorship,” at the Book Expo America (BEA) in New York’s Javits Center on May 27. The author, Alexa Olesen (a former AP correspondent in Beijing), has made a great contribution with her research on this sensitive topic, which has been long ignored by many Western writers and publishers. With this report, the foreign authors have been warned that not only their Chinese colleagues but also they themselves could be victims of the authoritarian regime where freedom of speech is not guaranteed.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison til 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners, and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

The huge book market in China is a great attraction to all authors in the world, although they know vaguely that there is censorship there. Yet the devil is in the details: only a small group of them finds out that their work in Chinese appears in a distorted shape; sentences and lines have been displaced, deleted or even changed, and that is not the bad work of the translator, but the ill-intended deed of the editors, who then again are not handling it alone. They are only receiving orders; the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP) is the key organ, the agitating devil behind the screen.

The report has pointed out the two main criteria for censoring: black (politics) and yellow (sex). It is indeed a very wide range. Those “cultural bureaucrats” are either knowledgeable or fans of literature and art; they have only one measure in mind: make no mistake, take no responsibilities. As soon as they confronted with words like, “Tiananmen incident,” “Falun Gong,” “Dalai Lama,” or “Great Famine,” the alarm bell tolls. China insiders Peter Hessler, Ezra Vogel, or Evan Osnos become the same victims of the censorship as authors of the fine arts, like poet Robert Hass, Paul Auster, Saul Bellow, Raymond Carver, Nathan Englander, Joyce Carol Oates, and Philip Roth.

Even the president of PEN America, Andrew Solomon, has to bend low in front of the censors’ cutter. Not to mention politicians like Henry Kissinger and Hillary Rodham Clinton; when their memoirs recite their personal experiences with China, dozens of “minefields” are waiting for them. The Chinese writer Yu Jie made a comparison of the Chinese and Taiwanese version of Clinton’s 2003 memoir Living History, through which he found out that the parts about human rightist Harry Wu and the labor camp, as well as the part about women rights, have been cut out in the mainland version.

Lady Clinton reacted harshly; she demanded her book be taken off the shelves. Therefore, no Chinese publisher dares to touch her latest book, Hard Choices, from 2014, since there is a passage about the blind lawyer Chen Guangcheng, who fled in an incredible adventure from his surrounded home in the night and escaped hundreds miles away into the American Embassy in Beijing.

Actually all these forbidden topics are open secrets and have been written and spread out in Chinese society, yet through a foreigner’s eye and pen, it becomes much more authentic. The Chinese authorities put all these under the category of “spiritual pollution,” alias “black”, an invented term since the 80s. The pollution should not be spread out, it must be prevented and stopped. In these sense, novels like Fifty Shades of Grey, belonging in the unhealthily “yellow” category, would have no chance to enter the official mainland market. The moral—at least the moral of the high cadres in China, with their unsaturated greed for power and sex—is no better than the rest of the world.

Between “black” and “yellow” there is a large grey zone. Chinese writers are sophisticated enough to take advantage of mooching in this area. Even the party-darling, Nobel literature laureate Mo Yan, has illustrated in his novel, Frog, that during the three years of the Great Famine, the hungry people—villagers and school children—were eating resin containing coal. Women did not become pregnant because of hunger. This forbidden topic has been embedded in the story with humorous language, allowing it to escape the censorship.

Another famous writer from Tianjin, Feng Jicai (1942-), has openly enjherd the grey zone in his describing of the frantic years of the Cultural Revolution. The horrible story of a female physician, out of fear, under the plea of her parents, first killed her father, then she and the mother jumped out of the window. Only she survived. This true story is one of Feng’s reportages, Ten Years of One Hundred People, the recording of common people’s fate during the Cultural Revolution [also under the English title, Ten Years of Madness]. This book was disseminated widely, and can be download online. Today, Feng is the vice president of the official China Federation of Literary and Art Circles.

Jia Pingwa’s novel, Abandoned Capital (Fei du, Beijing, 1993), has had a different fate. It has been stigmatized as “yellow,” abandoned and forbidden in China for 16 years, because it contains the erotic description of the sex between the protagonist and several females. In 2009, the book was reprinted in China, and it still contains the trace of deletions with remarks such as, “…” followed by parenthesis; in parenthesis, it reads: “so and so many characters have been deleted,” a common method used to handle the so-called pornographic literature, e.g. the famous classic Jin Ping Mei (The Golden Lotus) from the Ming dynasty.

Foreign writers cannot enjoy the treatment with the grey zone though, because of the scrupulous censors. The more they cut and delete, the safer for them. The PEN America report gives some recommendations to those who want to be published in China and accept to certain stand of the cut. There are writers who do not want to be censored: Evan Osnos wrote on China for The New Yorker for years, and published his book, Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China, in Taiwan, instead of China. Peter Hessler, who once worked two years in Sichuan and has already published three books in China, makes a combined decision. He believes there is still room enough for the Chinese reader to find out what he is aiming to tell them, although it is different from case to case. For example, he has refused that his recent book, Oracle Bones, be published in China, because the censorship will change the main tone of the book. His alternative is Taiwan. That is also the recommendation of the report-writer Olesen, who has suggested Taiwan and Hong Kong as alternative choices for Chinese publishing.