Wax and Gold

by Chalachew Tadesse / May 5, 2015 / 3 Comments

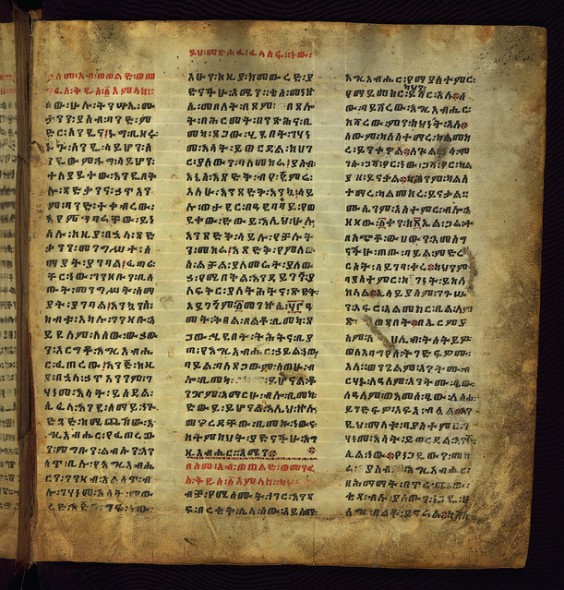

An illuminated Ethiopian manuscript. Photo via Flickr user: Walters Art Museum Illuminated Manuscripts.

A tribute to the late professor Donald Levine (Liben Gebre) and a decoding of the Amhara people’s most complicated methods of communication.

“We have in fact, two kinds of morality, side by side: one which we preach, but do not practice, and another which we practice, but seldom preach.”

-Bertrand Russell, British philosopher

Levine’s Genesis in Ethiopia

Since the late 1950s, Professor Donald Levine, a renowned American sociologist, has been a towering figure in Ethiopian scholarship. Levine was a devout Ethiopianist to the bone: a staunch advocate of the Ethiopianism movement, believed to be a precursor to Pan-Africanism. Sadly, Levine passed away on April 5th at the age of 83.

- This column’s topics will include literature, art, education, history, and political culture in Ethiopia, as well as society and politics in the Horn of Africa. Moreover, I will address the tribulations of journalists and the ill-fated constitutional right of freedom of expression under Ethiopia’s deceptive authoritarian regime. I will try to be the voice of the voiceless, be it persecuted journalists at home or exiled journalists abroad. These themes will make Ethiopia’s uniqueness and absurdities evident.

- Chalachew Tadesse is an Ethiopian journalist and columnist. He has previously worked as a full time journalist for The Reporter and The Sub-Saharan Informer English newspapers. He was also a columnist for the much-acclaimed Fact magazine, before the Ethiopian regime closed it in October 2014. A political science student by training, he works as a university lecturer and is known for his sociopolitical commentaries on the Ethiopian private press.

The late Levine wrote his Ph.D. on the Amhara ethnic group (to which I personally belong) of north-central Ethiopia. Levine was an advisor to Emperor Haileselassie I, Ethiopia’s last emperor, who claimed to have descended from the Biblical King Solomon of Israel and Queen of Sheba (Makda) of Ethiopia (then called the Axumite Empire). In fact, Levine also advised the American Peace Corps mission in the 1960s and served as a lecturer in the then-Haileselassie I University College, now Addis Ababa University.

But before anything else, I feel obliged to affirm that nature and Orwellian rulers have long been the twin merciless enemies of the Amharas, so much so that they often conspire against the people, so to speak.

As he was a tenacious ethnographer, Levine mastered Amharic, the Amhara language and, of course, Ethiopia’s lingua franca. Recently, he had also adopted an Ethiopian name, Liben Gebre Ethiopa, and was addressed as “Liben” in all situations.

Levine had initially added a traditional military title called fitawrari (almost equivalent to “general”) to his name. Levine told the late prime minister Meles Zenawi about his new name before making it public. Ironically, Meles responded “except the fitawrari, the rest is ok” thereby forcing Levine to drop the fitawrari title. Alas, Meles was always at odds with the greatness of Ethiopian history and tradition. In fact, Levine was always aware of this.

By the way, ethnographers often face a dilemma between impartial scholarship and advocacy for the rights of the people they study. They usually create special affiliation with the people they study. Notwithstanding his close association with the Amhara, Levine, I think, walked the thin line cautiously and avoided falling into this trap.

Levine always saw multi-ethnic Ethiopia as a unified single polity. So much so that it was to him, I quote, “a synthesis of the Amhara thesis and the Oromo antithesis.” He interpreted Ethiopia through Hegel’s glass, following the Hegelian paradigm of “thesis-antithesis-synthesis.” And yet he rightly argued that at a national level, the Amhara culture is the single most indigenous cultural tradition, unlike the rest of Africa.

Single-mindedly, Levine studied the anatomy of the Amhara people, including the most complex “wax and gold” that pervades the Amhara way of life. In his widely-acclaimed masterpiece, Wax and Gold: Tradition and Innovation in Ethiopian Culture (1965), he wrote: “Wax and gold is a key to the genius of Amhara culture and a highly distinctive Amhara contribution to Ethiopian culture.”

It would therefore be a disservice to the late professor Donald Levine if this column failed to revisit the ingenuity and literary worth of “wax and gold” in Amharic oral literature, as a tribute to Levine. Oh, there is one more thing: the young Levine grew up near the city of Pittsburgh, where Sampsonia Way is located.

The Mystery of “Wax and Gold”

Etymologically, “wax and gold” (sam-enna warq in Amharic) traces its origin to qene, a sophisticated religious work composed in the ancient Geez (Ethiopic language). After mastering the Geez and qene through two to five years of intensive study in informal qene schools, deacons in Ethiopia’s Orthodox Church services normally recite the Qene. “Wax and gold” is a serious intellectual exercise different from ordinary poetry.

“Wax and gold” is, therefore, both an ambiguous mode of communication and way of life among the Amhara people. Often composed in the form of poetry or prose, it contains double meanings. But it is a serious intellectual exercise that differs from ordinary poetry. Whereas the “wax” connotes the apparent figurative meaning, the “gold” contains hidden and ambiguous meanings. As it is the most complex form of Ethiopian intellectual and literary tradition, scholars somehow equate it with allegory of the western mode of communication.

“Wax and gold” benefits from the fact that several Amharic verbs have double or triple meanings and an Amharic word can also be interpreted in more than one way. Moreover, the pronunciation of some consonants can also be prolonged.

Let me unmask the mystery of “wax and gold” with examples that were often used in my high school Amharic courses.

Yabbat edda la-lijj yebal nabar dero

Bayat edda gabahu enne-ma zandro

(In olden times a father’s debt was passed down to son

But today I inherited debt from a grandfather)

Having been logically derived from the first verse, the second verse “but today I have inherited debt from a grandfather” becomes the “wax” precluding the listener from comprehending the speaker’s real intention.

But the pun (hebere-qal, or the double-layered word) is “bayat” in the second Amharic verse; it could mean either “grandfather” or “when I saw her.” So, when the concealed and real meaning is untangled, the phrase becomes quite different: “But in my case, it was the sight of her that put me in debt (trouble).” Mind you, the speaker’s intention is to tell us about falling in love with a woman at first sight under the disguise of talking about a debt from a grandfather.

Yeferenjun wutet bermel ametachehu

Yerasachen eka enesera eyalkuachehu

(You brought me the fereenj’s barrel

Whereas what I asked for was our own local pot)

In the first verse “yeferenjun…bermel” refers to a barrel made by the “ferenj” (all white men are referred as ferenji). In the second verse, the underlined word enesera means a local pot made of clay; an equivalent of a small barrel. So, the speaker is saying: “You brought me a ferenj barrel when I asked for our own local pot. “

Make no mistake, “wax and gold” cannot be disregarded as an irrelevant mode of communication. Despite its gradual decline in usage, “wax and gold” enables people to express satire, humour, deception, intrigue and even disguised insults. It serves as an instrument of self-defence, reciprocity or objection in latent form. For that matter, it can be used as a safety valve to cool off our temper without direct confrontation.

Normally, the Amhara culture requires “fastidious etiquette in social relations,” the reverence for norms that Levine observed. One can use “wax and gold” to simultaneously flatter publicly or curse somebody secretly, including authority figures. That is how the ethos of “wax and gold” serves as a survival strategy.

Before I conclude this piece, I feel obliged to compose my own “wax and gold” for Levine, drawing upon my recollection of it from my high school years almost 20 years ago.

Liben Gebre yemilut bizu tarik tsifual

Tinshum tilqum quch belo yanebal

(Much was written by Liben Gebre)

All the little and the elderly will sit down and read)

The “wax” is just the English translation above; since Levine wrote several works, all people will settle down and read his books. That is the meaning you can derive logically from the first verse.

But my pun in this poetry is the underlined word “yanebal,” which could mean “read” or “weep/shed tears” depending on the usage of stress in the pronunciation. If you pronounce it without stressing “ne” and “ba”, the meaning becomes “shedding tears.” So, what I am telling you covertly is this: all Ethiopians will sit down and shed their tears to mourn the great Liben Gebre.

Professor Liben, Ethiopia owes you a lot. May your soul rest in peace. And of course I should also say the same to my fellow countrymen massacred in cold blood on April 10th by the Islamic State group in Libya.

3 Comments on "Wax and Gold"

I just wonder about the words that might have been inscribed on Levine’s grave, for he was always uniquely in love with Ethiopia. A wonder as to whether something about his passion for Ethiopia was inscribed.

The author

Nice article and interesting…

Thank you for sharing the deeper meanings of ‘wax and gold’ in the Ethiopian literary and oral traditions. Most interesting.