Notes on (Egyptian) Nationalism

by Nesreen Salem / February 19, 2015 / No comments

The anniversary of the Egypt’s 2011 Revolution sees a country with a renewed nationalistic fervor.

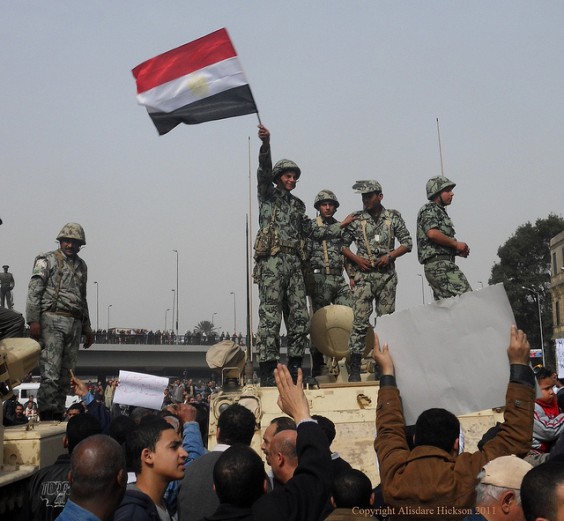

Soldiers wave the Egyptian flag over Tahrir Square. Photo via Flickr user: Alisdare Hickson

“I have known the inexorable sadness of pencils,” starts Theodore Roethke‘s poem “Dolor.” Thus this heaviness with which I write is explained. Words are weighed down by the continuous grim events that have reaped one life after another in Egypt in recent weeks.

- A Thousand and One Cries will use a literary edge to reflect on Middle Eastern cultural and political trends, paying special attention to the condition of women and other minorities in Egypt.

- Nesreen Salem writes fiction and commentary on political and cultural affairs in Egypt and the Middle East. Although her heart is in Alexandria, the city of her birth, she lives in England. There, she works as the Egyptian Feminist Union’s UK Coordinator and a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Essex. Her field of research includes history, feminism, myths, legends, and fairy tales. Currently, she is writing her first novel and a collection of poetry.

The anniversary of the January 25 revolution has not passed unstained with fresh, innocent blood, blood that is mixed with the memory of 2011’s euphoria and the relentlessly lingering hope and desire to witness the actualization of its promised fruit. Clutching onto asphalts and pavements, this iron scent of heroes still lingers.

Corpses have been mounting since, in and out of jails, and the oasis of hope is fast turning into a wasteland of despair. The regime’s machinery, far from being detached, is oiled anew, fueled by the nationalistic hysteria and jingoism that the media – and citizens – are all-too-eager to wail.

It is this ultra-nationalism – which must not be confused with patriotism – that George Orwell warned about in his essay “Notes on Nationalism.” One need only turn to the much-feared beast of ISIS to learn where unyielding nationalism can lead. Much of his outline of the principles of nationalist thought can be found among Egyptians as well as within ISIS ideology, making us the mirror reflection of our supposed worse enemy.

Egyptian nationalists – among whom stand many leftists and liberals – are obsessed with the superiority of the military institution, recalling its historical victories and juxtaposing them with the military failure of neighboring nations. Similarly, the ISIS ideology depends on its followers’ obsession with evoking a glorious past where Islam ruled over nations and empires. Hence any opposition or rivalry that may arise is swiftly dealt with, and if extreme force is used to suppress it, then why not? Murder of the opposition is a justified means to the fabulous end.

In his essay, Orwell states that: “Nationalism is power-hunger tempered by self-deception,” explaining its mechanism as a drive that works defensively against a perceived common antagonist rather than from a motive of loyalty to land or country. Even the most fervent forms of nationalism are not impervious to their frail core. The basis this nationalism stands on is the double standards that manifest themselves in almost every aspect within Egyptian culture. Egyptians are a religious people, yet they refused to accept an Islamist leader or government. They admire the West’s relatively progressive governance, yet they refuse the idea of replicating it even partially. They like the idea of democracy, yet they don’t believe they’re ready for it. So we end up with a nationalism that is empty and vulgar; dishonest and loud.

The fight for a better Egypt has shifted its battlefields long ago. This apathy, this all consuming lethargy that has swept us back to an era even worse than Mubarak’s in the name of nationalism, is where the battle must begin. It is a moral one. One that forces us to look within and recognize the contradicting duality through which we view and assess our culture and our lives. Naguib Mahfouz‘s infamous patriarchal character Si el Sayyed, of The Cairo Trilogy</em>, was not an anomaly; indeed he still stands as the icon of cultural norm.