Smoking a Pipe on Auguste Dupin’s Divan: Clues for Reading a Scandal

by Israel Centeno and translated by Kelly Harrison / June 18, 2013 / No comments

What truths might we learn from Poe’s lounging detective?

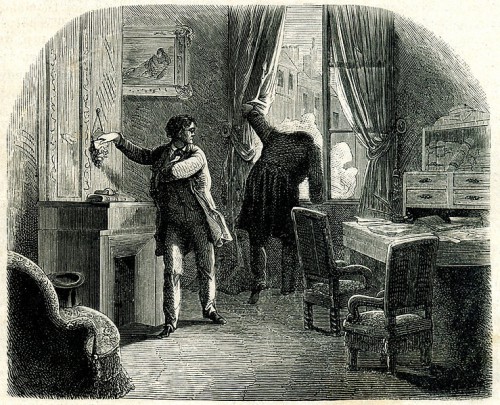

Drawing of a scene from Edgar Allan Poe's short story 'The Purloined Letter.' Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Edgar Allan Poe, in addition to opening the way for the modern detective novel, created the paradigmatic point of view of the cynical, sedentary detective. Towards this end, as Alexandre Dumas had done previously, Poe used political scandal as the backdrop for constructing the plot of his detective stories.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

For example, in “The Purloined Letter” the chief of the French police asks a sedentary private detective for his help in recovering a letter that has been stolen from the queen, or Madame X (reminiscent of the necklace in the hands of Cardinal Richelieu in The Three Musketeers), that will be used to blackmail her husband politically, with the ulterior motive of ruining his career, deposing him, or having him executed.

Our cynical and sedentary detective, Auguste Dupin, tells the police chief that even though this is an easy case, it will be impossible for him to solve it—although he does recommend going back to search the blackmailer’s office. At this point Dupin has a brilliant line in the story which, as I paraphrase, goes something like this: “You can take D’Arcy’s studio apart again, piece by piece, but you’ll find nothing because you don’t understand how his mind works.”

Setting aside the interpretation of the story for a moment and jumping straight to the solution, it would be that the best way to hide something extremely large and conspicuous is to place it squarely in the middle of a picture window. We might also turn from this little divertissement towards the other substrate of the story—the political scandal itself—to understand what it entails and how it is approached by those who would analyze it.

The first thing that comes to mind is that scandal is an time-honored and highly-esteemed implement, an art form as old as the throne itself and ever-present at the seat of power. The story lines and causal motifs of The Three Musketeers and The Purloined Letter are exemplary stories of scandal.

The obligatory, clichéd elements include blackmail, political purges, and assassination. These elements arise in the course of the manipulation of one of the actors of the political contexts that inform the story and the exposure of his or her shocking transgressions. The iterations of the obvious, the controlled interplay of the forces in conflict, and the leaked revelations of secrets, all serve a specific purpose. Then comes the betrayal and we see one of the characters fall from grace in a move that is seemingly advantageous to all sides of the conflict in the story. This is followed by pacts and realignments, sometimes among friends and allies, other times between enemies.

Every time we’re confronted with the shameful facts of the latest scandal that reveals corruption connected with the government and the rise of a “new” elite, we can’t help but think of Auguste Dupin and feel the temptation to apply his implacable logic, which looks beyond the obvious and the platitudes and seeks to understand the mind of those who leaked the scandal and those who sought to use it to their advantage. Perhaps there is something in the middle of all this corruption and putrefaction, something all too obvious that has escaped the impeccable and implacable analyses of the specialists and remains just out of view. In the end this will turn out to reveal what is most fundamental—the heart of the matter, the true crime, the real criminals.

Translated by Sam Cogdell