Latin American Writers and the Crisis in Spain

by Horacio Castellanos Moya / March 14, 2013 / No comments

Madrid and Barcelona are currently the epicenters of literature in Spanish, but Spain’s economic crisis puts that position—and all literature in Spanish—into question.

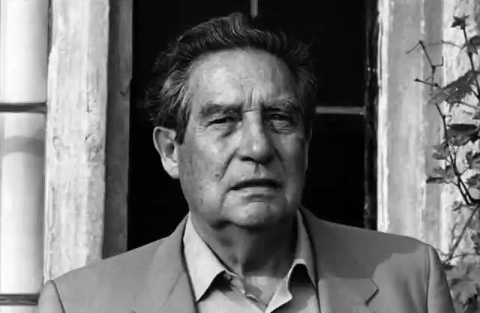

Nobel laureate and poet Octavio Paz directed Vuelta, an internationally known Spanish literature magazine. Photo:Youtube user elsenin.

The profound economic and social crisis in Spain is changing the landscape of the publication and distribution of Latin American literature. Over the past several decades, thanks to the surging Spanish economy, Barcelona and Madrid had come to be the two capitals of literary culture for writers in Spanish, including both those from Spain and from Latin America as well. But the drastic shrinking of the Spanish market and abrupt budget cutbacks in funding for culture, and literature in particular, may alter their status as literary metropolises.

- Corkscrew is focused on Latin American issues. Literature, journalism and politics are the main concerns of this column. A corkscrew is useful only if it opens a bottle, hopefully full of something that would enlighten our spirits, but we could also set loose a cruel Genie or a rotten wine. The author will follow this principle: look for topics that open debates, new perspectives, and controversy. Cheers!

- Horacio Castellanos Moya is a writer and a journalist from El Salvador. For two decades he worked as a journalist in Mexico, Guatemala, and his own country. He has published ten novels, five short story collections and two books of essays. He was granted residencies in a program supported by the Frankfurt International Book Fair (2004-2006) and at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh (2006-2008). In 2009, he was a guest researcher at the University of Tokyo. Currently he teaches at the University of Iowa.

The notion that for every language, there is one city with the exclusive power to generate literary prestige has been the subject of debate and questioning. Still, it is an idea that isn’t difficult to understand: New York, and London before it, have long been considered the Meccas of English-language writers. For example, as brilliant as an Australian or South African writer might be, his or her work would have to clear a formidable regional barrier without the recognition of publishers and critics in the two metropolises mentioned.

In the case of literature in Spanish, however, Madrid and Barcelona were not always the generators of literary prestige. Throughout the twentieth century, other Latin American cities performed this role, mainly for reasons related to the dictatorship of Francisco Franco and the poverty that Spain endured during his rule. Buenos Aires played the part until the mid 1970s, when the military shut down literary activity for the most part. But before this, the leading publishing houses with the capability to disseminate books throughout Latin America were located there, and the great majority of translations of international literature were produced there as well. The group of writers affiliated with the magazine Sur also set the standards of literary taste, but the production and dissemination of books in Buenos Aires was rich and diverse. It’s no coincidence that the fundamental works of Nobel Prize-winning fiction writers Miguel Ángel Asturias and Gabriel García Márquez were launched from the River Plate area.

During this same period, in the excitement that followed the Cuban Revolution, Havana came to be known as the center for the canonization of writers espousing progressive ideas and social change, thanks to the establishment of new publishing houses and the magazine Casa de las Américas and its literary prizes. This role lasted less than a decade, however. With the arrest of the poet Heberto Padilla in 1971, Havana’s prestige began to leak and take on water, until it finally sank along with the Cuban dictatorial model itself.

Mexico City has also played a significant role as an arbiter of literary prestige and distribution in Latin America. Its literary scene was enhanced first by the arrival of Spanish publishers and writers expelled by Franco, and again in the mid 1970s, when the dictatorships of the Southern Cone countries began driving writers and intellectuals into exile. The influence of Vuelta, the literary magazine directed by Nobel laureate Octavio Paz, was decisive at the time, not only for literature written in Spanish, but also at the international level.

If Madrid and Barcelona ceased being the arbiters of literary prestige for Latin American writers, what would come next? What new place would dictate the criteria of taste? Would the role revert to a Latin American city? It’s too early to say. What’s certain is that any change in this scenario could only come about as a result of a major breakup in the Spanish-language publishing industry. But I’ll address that topic in my next column.