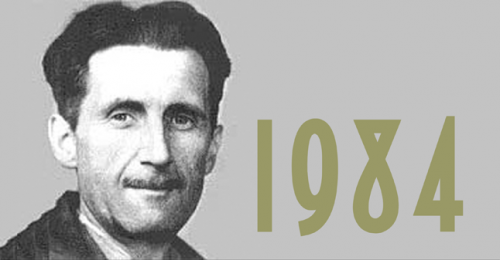

Orwell’s 1984 and Totalitarianism, Pt. I

by Israel Centeno and translated by Kelly Harrison / November 20, 2012 / 7 Comments

The Spanish Civil War and Orwell’s changing politics.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Below is part one in a short series of articles concerning George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, two paradigmatic novels that address the issue of a future without freedom, from subtle dictatorships to totalitarianism. Read part two here.

In order to understand George Orwell’s novel 1984 we must clearly define the term “dystopia” or “anti-utopia.” If utopia represents the best of all worlds, definitive freedom, the place where the dreams of men come true, then dystopia is the worst of all worlds, the loss of definitive and absolute freedom, and the submission to power with absolute control over human will. Paradoxically, the more definitive and absolute that level of control is, the happier the people living under such circumstances are.

- From his lonely watch post Albert Camus asked who among us has not experienced exile yet still managed to preserve a spark of fire in their soul. “We’re all alone,” Natalia Sedova cried in exile on hearing of her husband Leon Trotsky’s affair with Frida Kahlo. In his novel Night Watch, Stephen Koch follows the incestuous love affair of David and Harriet, wealthy siblings watching the world from their solitary exile. Koch’s writing, Camus’s theories, and Trotsky’s affair all come back to exile and lead me to reflect on the human condition. From my own vantage point, my Night Watch, I will reflect on my questions of exile, writing, and the human condition.

- Israel Centeno was born in 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela, and currently lives in Pittsburgh as a Writer-in-Residence with City of Asylum/Pittsburgh. He writes both novels and short stories, and also works as an editor and professor of literature. He has published nine books in Venezuela and three in Spain.

Although the idea of utopia has taken hold of our collective and individual imaginations since Thomas More’s work of the same name (1516), and its true political realization has been sought in the Jesuit missions in Paraguay, the utopian French socialists’ phalanstères of the 19th century, the Fabian socialism of H. G. Wells, and the determinism of Jack London, at any moment, the idea of a utopia could split from political theory and enter the exclusive realm of literary creation. With that in mind it could be said that the idea of a utopia gave rise to the genre known as science fiction. Utopian literature features fantastic journeys to distant lands, where proposed models of supreme happiness are put into practice.

It could be said that Erewhon by Samuel Butler (1872) is one of the fundamental works of utopian literature, whose title is an anagram for “nowhere,” or to put it another way, “utopia.” However, at that time, knowledge of the world was limited, and reality sometimes forcefully imposed itself upon certain modes of thinking. In 1911, following the first successful expedition to the South Pole, there was nowhere in the world that man had not been and, perhaps, to be more precise, there was no reality nor foreign human condition left unexplored. Consequently, from that point onward, the search for utopia was focused on the future, or on other lands and other worlds. The utopian and adventure genres converged and the creative production of science fiction became more prominent: The Time Machine, The Invisible Man, The Call of the Wild. But then the world war years came to pass and changed how the universe was interpreted. Above all, they changed how mankind and its future was perceived.

While the Russian revolution suggested that a utopia was possible, it didn’t take long for serious warnings and differing points of view to arise, particularly through literature, highlighting perhaps how horrifying the future could become if power was amassed, if it was concentrated in the hands of a few or held by just one person, or if the collective dream was usurped by a private leadership. And if all this became reality, the perception man had of the world would end up being manipulated and those who suffered a drastic loss of freedom would proclaim the greatest levels of freedom never lived.

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin (1921), Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (1932), and War with the Newts by Karel Čapek (1936) were the first literary works to demonstrate this.

But it was 1984 that would become the most famous dystopian novel, the culmination of a literary tradition that warned us of the dangers of the concentration of power. Following Orwell’s experiences in the Spanish civil war—where he witnessed the pugnacity of Stalinist repression in its ability to persecute and purge the Trotskyists and anarchists in Spain; where he lived through collectivization and its self-management on the Aragonese front; where he experienced the civil war within the civil war when the Republican Army, armed by the Soviet Union and the Comintern, persecuted, captured, executed, eradicated, and demobilized the Trotskyist and anarchist militias—Orwell suffered a significant blow to his convictions, leading him to declare that orthodox communism was another type of dictatorship, comparable to Nazism. Two sides of the same coin. He then went on to denounce the manipulation of information and propaganda within Stalinism, which made it appear, for example, as if the elimination and execution of the Trotskyists in Barcelona had never even happened.

7 Comments on "Orwell’s 1984 and Totalitarianism, Pt. I"

Trackbacks for this post