Death at Their Heels

by Horacio Castellanos Moya and translated by Sam Cogdell / November 8, 2012 / No comments

The beautiful desperation of a writer confronting his own mortality.

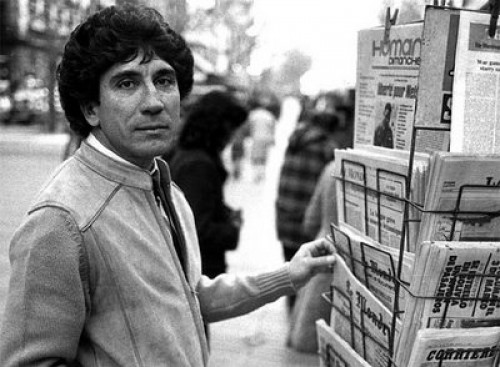

Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas. Photo: flickr user Cristee Dickson.

I’ve recently reread the book Viaje a La Habana (Trip to Havana) by the Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas (1943-1990). It’s made up of three pieces of narrative fiction that are independent of one another, but are joined together by a certain power that runs through them all. Arenas was not a stylist, but a writer-volcano who always wrote without stopping, with the compulsion of someone who lacks all sense of the future. This was especially true for him because the Cuban police and prison guards devised ingenious plots for seizing his manuscripts whenever they could get their hands on them.

- Corkscrew is focused on Latin American issues. Literature, journalism and politics are the main concerns of this column. A corkscrew is useful only if it opens a bottle, hopefully full of something that would enlighten our spirits, but we could also set loose a cruel Genie or a rotten wine. The author will follow this principle: look for topics that open debates, new perspectives, and controversy. Cheers!

- Horacio Castellanos Moya is a writer and a journalist from El Salvador. For two decades he worked as a journalist in Mexico, Guatemala, and his own country. He has published ten novels, five short story collections and two books of essays. He was granted residencies in a program supported by the Frankfurt International Book Fair (2004-2006) and at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh (2006-2008). In 2009, he was a guest researcher at the University of Tokyo. Currently he teaches at the University of Iowa.

The last two stories in Trip to Havana, “Mona” and the title piece, were written when Arenas was already ill with AIDS and knew that his days were numbered. His prose gallops along at a surprising clip, yet it never gets away from him, takes shortcuts, or digresses. Arenas handles the reins like a consummate horseman.

Reflecting on this rereading, and recalling the painful circumstances the author suffered through while he was writing these pieces, I wondered how much his prose was influenced by the certainty of his impending death, along with his knowledge of the disease that was consuming him and just how little time he had left to live. We all know we’re going to die, of course, but as the proverb says, “It’s one thing to see death on the distant horizon; it’s another thing to look death in the face.”

There must be a violent change in the soul’s outlook, an upheaval in the way of seeing the world, a change in respiration, an altered rhythm of breathing that spreads to the writer’s prose. The efficacy of language responds not so much to a narrative strategy as to a condition of life in which anything superfluous, anything that gets in the way, is categorically eliminated in the writer’s mind. Every minute counts, and every word and every phrase takes on another dimension in which the luxury of even the slightest waste is no longer allowed.

That’s the impression this rereading of Trip to Havana made on me. And it’s the same one that I got from rereading Arenas’ Before Night Falls as well, although because that piece is a memoir—in other words, it’s about the image of himself the writer wants to leave for the future—Arenas has less freedom than in fiction, and he’s obligated to explain himself, to justify himself, perhaps even lie to himself and to his readers, for the purpose of making his memories fit into the image of himself he wants to project.

Throughout history, there have surely been great writers who have written their final works with death at their heels, sometimes leaving them unfinished. Their prose hits the reader with such force that it subjugates and hypnotizes him, perhaps because the desperation of a man touched by death is concentrated in all of their sentences, like the wild gesticulations of someone who demands our attention for one last instant. The first three names that come to me are the Proust of In Search of Lost Time, the Bernhard of Extinction (although this novel was not left unfinished), and the Bolaño of 2666. Desirous readers can add to this list many times over.