“Ineducable, Even in Reeducation Camp”

by Tienchi Martin-Liao / August 29, 2012 / 1 Comment

Writer and social critic Wang Xiaoning is released after ten years in prison

Yu Ling is a bit out of breath; the thermometer has almost climbed to 90 degrees Fahrenheit, totally unusual in Beijing. Maybe by end of the month it will be cooler, she thinks. And although she does not clean alone, as her son and daughter-in-law are with her, Yu is still tired. They have repainted the inside of the house, repaired the leak in the bathroom, and even replaced the old sink in the kitchen. Wang Xiaoning, her husband, will like it, she thinks. He should have a good impression of their home. After all, it has been ten years since he last saw it.

- During the Cultural Revolution, people were sentenced to death or outright murdered because of one wrong sentence. In China today writers do not lose their lives over their poems or articles; however, they are jailed for years. My friend Liu Xiaobo for example will stay in prison till 2020; even winning the Nobel Peace Prize could not help him. In prison those lucky enough not to be sentenced to hard labor play “blind chess” to kill time AND TO TRAIN THE BRAIN NOT TO RUST. Freedom of expression is still a luxury in China. The firewall is everywhere, yet words can fly above it and so can our thoughts. My column, like the blind chess played by prisoners, is an exercise to keep our brains from rusting and the situation in China from indifference.

- Tienchi Martin-Liao is the president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center. Previously she worked at the Institute for Asian Affairs in Hamburg, Germany, and lectured at the Ruhr-University Bochum from 1985 to 1991. She became head of the Richard-Wilhelm Research Center for Translation in 1991 until she took a job in 2001 as director of the Laogai Research Foundation (LRF) to work on human rights issues. She was at LRF until 2009. Martin-Liao has served as deputy director of the affiliated China Information Center and was responsible for updating the Laogai Handbook and working on the Black Series, autobiographies of Chinese political prisoners and other human rights books. She was elected president of the Independent Chinese PEN Center in October 2009 and has daily contact with online journalists in China.

On August 31st Wang Xiaoning will be released from prison. In September 2002, Wang was arrested at his Beijing home in front of his wife and son. Born in 1950, Wang, the son of a minister, was raised in a family of high cadres. Had he behaved obediently, he could have had a good career enqueued among the “princelings.” Instead he chose a thornier path: Advocating for freedom and democracy in his country.

In the 1990s Wang studied engineering and worked as technician and businessman. In 1999 he created a website and started writing political commentary and analysis criticizing corruption and the government’s policies behind building the Three Gorges Dam. He also wrote a series of articles emphasizing the necessity of political reform in China.

His articles touched on sensitive topics like publication law, election regulations, and the corrupt military system in China. Wang even drafted a constitution. But his “anti-party and anti-socialism” writing alarmed the authorities, and his house was raided. Files and computers were confiscated. When Wang’s articles were published in the overseas online journal Democratic Forum the authority accused him of collaborating with foreign anti-China forces and arrested him. Because Wang disseminated his writing online and through his Yahoo account, the police pressured Yahoo to give Wang’s IP address to them. The court used this information as evidence of his crime and sentenced Wang to ten years in prison, accusing him of “inciting subversion of state power.”

China began the millennium with an image of iron and blood. Criminal law was amended in 1997, and the old terminology “counterrevolutionary propaganda crime” has been baptized with a new name—“inciting subversion of state power.” Nevertheless, the substance remains the same; it is still the state’s handy instrument to tame dissidents. Wang Xiaoning was one of the first severe cases of political persecution under the amended law, though there have been dozens of other cases of literary inquisition since the beginning of this century. If you break the will of the people and tread down their dignity, then they become a kind of dough that you can form as you like.

This is the secret of the Chinese Communist Party. With this tactic they have ruined generations of intellectuals. Yet there are still enough individuals made of special material who are irrepressible. In Chinese terms, these people would be called “ineducable” even when they are thrown into the “reeducation camp” and brainwashed for years. Wang Xiaoning is this kind of person. He has refused to show any regret or admit that he committed a crime. Had he bowed to the pressure his sentence would have been reduced to three years, but Wang stayed firm and served the full ten year sentence.

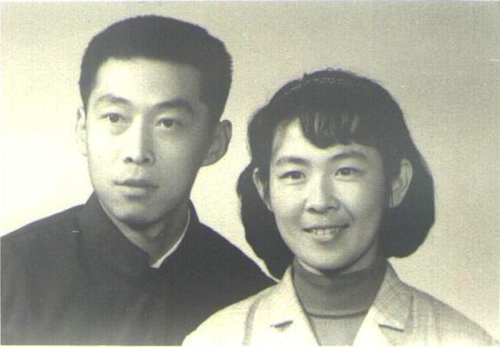

At the end of August, when he comes out of prison, we will see a thin, fragile man with grey hair whose eyes are still bright and sharp. His brave, slim wife, also in grey, will welcome him warmly. The pressure she has suffered over the past ten years has been no less than his. And while time does leave traces on their appearance, neither their spirit nor their will have been broken. They are higher then ever.

One Comment on "“Ineducable, Even in Reeducation Camp”"

Dear Tienchi, you should know best that even in Germany there are more political prisoners than you would have imagined due to disregard of political correctness and political lies.