The Nightmare of the Entertainment Society

by Horacio Castellanos Moya / July 19, 2012 / No comments

On Mario Vargas Llosa’s new collection of essays

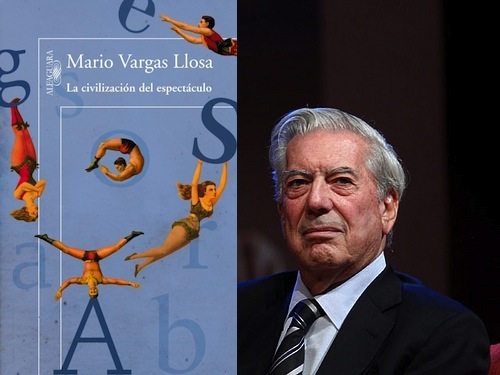

Left: La civilización del espectáculo. Right: Mario Vargas Llosa. Photo: Globovisión. Creative Commons.

There’s no point in striving to produce an enduring work of literature, or writing something intended to immortalize its author, or exploring the depths of the human condition. Such projects are meaningless in times like ours, when values and priorities have become misplaced. The only things that matter are diversion and entertainment, and we’re tyrannized by all things lite, trendy, and disposable. Frivolity is the new rule, and the only values of consequence are those of the market.

- Corkscrew is focused on Latin American issues. Literature, journalism and politics are the main concerns of this column. A corkscrew is useful only if it opens a bottle, hopefully full of something that would enlighten our spirits, but we could also set loose a cruel Genie or a rotten wine. The author will follow this principle: look for topics that open debates, new perspectives, and controversy. Cheers!

- Horacio Castellanos Moya is a writer and a journalist from El Salvador. For two decades he worked as a journalist in Mexico, Guatemala, and his own country. He has published ten novels, five short story collections and two books of essays. He was granted residencies in a program supported by the Frankfurt International Book Fair (2004-2006) and at City of Asylum/Pittsburgh (2006-2008). In 2009, he was a guest researcher at the University of Tokyo. Currently he teaches at the University of Iowa.

So writes Peruvian author and Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa in his most recent book, La civilización del espectáculo (The Civilization of Entertainment) (Alfaguara, Madrid, 2012), a collection of essays in which he presents a pessimistic assessment of the current state of literature, the arts, and what used to be known as culture. He laments this state of affairs and has no illusions about the world to come: What he sees playing out across the board, from literature to politics, from religion to eroticism, is a “ludic banalization” of the spheres of human thought and action.

According to Vargas Llosa, we live in a “lite society that bestows the same supremacy on frivolity that in other times belonged to ideas and artistic production.” This frivolity “consists of an inverted or unbalanced set of values in which form is more important than content, appearance more important than substance, and where gesture and display—representation—take the place of feelings and ideas.”

In the entertainment society, “the highest priority in the current set of values is entertainment; and diversion, the escape from boredom, is the universal passion.” The generational imperative of the moment is “not to get bored, to avoid anything that disturbs us, causes us to worry, or makes us feel anguish.” The death of independent thinking and deep questioning is the order of the day. The intellectual as a reflexive subject who interrogates reality has ceased to be and has instead become a kind of buffoon who commands the public’s interest only as long as he or she plays along with the latest trendy game.

“Culture is diversion and what isn’t diversion isn’t culture,” writes Vargas Llosa.

In circumstances such as these, of course, it’s not surprising that “the most representative literature of our time turns out to be lite literature—light, insubstantial, and facile—literature that shamelessly aims first and foremost (and almost exclusively) to entertain,” and one that foments conformism in its worst forms: Complacency and self-satisfaction.

Vargas Llosa believes that underlying this new state of affairs in literature, art, and culture, is the fact that “the distinction between price and value has disappeared, and both are now one and the same . . . The former has absorbed and voided the meaning of the latter. Whatever is successful and sells is good, and whatever fails or doesn’t become a hit with the public is bad. The only value is the commercial value set by the market.”

It’s a pity that Vargas Llosa doesn’t push further in his criticism of the dictatorship of the market, because that would lead him toward a critique of the savage economic neoliberalism that is the true culprit responsible for the entertainment society. And the reason that Vargas Llosa can’t take his critique a step further, as Octavio Paz once did, is because he is an admirer and propagandist for the very neoliberalism that has created the society he criticizes. He identifies the problem, but not its cause.

Translation: Sam Cogdell