Blessed Body: An Interview with Unoma Azuah

by Abigail Meinen / July 5, 2017 / No comments

Image via the author.

Unoma Azuah knows the power of storytelling. As a young girl, her grandmother’s stories helped her navigate her identity, and journaling gave her a space to explore her thoughts and experiences. As the writer of Blessed Body, Azuah gave others in the Nigerian LGBT community the opportunity to do the same, through sharing their own stories of pain, hope, and joy. She currently lives in Chicago, and teaches writing at the Illinois Institute of Art, while staying closely connected to her Nigerian identity and community. Azuah spoke with Sampsonia Way about her writing process, spirituality, and her experience in the United States.

Can you talk a little about what the process of getting the stories together in Blessed Body looked like?

The process of getting Blessed Body stories all together started with me, because I always talked about how I felt burdened. I would ask myself, “Am I the only lesbian in Nigeria? What’s really going on?” Of course, I had friends, but I didn’t really feel like it was as burdensome for them as it was for me. So I decided to start talking about it, and there was one way to do that- through narrative. The LGBT narrative, as portrayed by the Nigerian media, is the cliche of demonizing sexual orientation. I felt that somebody had to start telling our story, otherwise one would always get the wrong impression about who we are. So that was one stage.

The second stage was actually getting people to share their stories. Some said, “Oh, I’m not a writer, you know, how can I do it?” And I said, “It’s okay, whatever you feel that you need to talk about, you should go ahead and write it.” And some still struggled with that, so I actually had to listen to some of them and then write it down. And when I was done, I shared it with them to make sure it represented what they meant. So that was the second stage.

For the third stage – because I wanted to represent as many LGBT voices as possible – I had to go to my friends’ friends’ friends. And some of them weren’t so comfortable talking to me because they didn’t know who I was. So they required another level of convincing: “It’s okay, I’m not about to out you or put you in any kind of danger.” So that helped. Some preferred that we meet in a public space. Then sometimes some would say, “Well no, I’m not comfortable with this anymore.” Then I would come up with suggestions like, “Why not use an anonymous name and not use your real name, and maybe instead of being specific about the cities, you can just mention the city close to you?” Gradually, I was able to collect a sizable number of stories for the book. Reading through them, when I was trying to edit them, was another intense experience, because halfway through I would be so angry and upset, and then in another minute I would be laughing out so loud! So there was a kind of balance that came from that process, and I did it every day. It was quite a fulfilling experience.

Somebody had to start telling our story.

Reading through the book was difficult at points, there is one page after another of so much pain – and then on the next page you are laughing at someone’s wonderful, funny experience. It’s really emotionally complex.

I think the good side to it is that there are stories that stay very determined and persistent, and there are stories that are proud. As much as much as many stories had to do with pain, there were also many that were defiant and hopeful.

There’s an entire section of the book on relationships formed through Facebook and the Internet, which have changed the LGBTQ experience for a lot of people. You have been writing through this time of the Internet coming into being; how do you think the experience of an LGBTQ person living in Nigeria has changed?

Blessed Body, by Unoma Azuah.

It really has changed, and it’s become quite progressive because Facebook and social media gave some of us in Nigeria the outlet to see other LGBT people around the world. There’s something affirming about it. It also gives people the platform to form communities. So I would say that it has made life a whole lot easier and a whole lot more accessible to so many things that weren’t accessible years ago, before social media. That’s helpful as writers because so many readers in other countries have met through Facebook as well.

You write stories about youth in Nigeria and youthful innocence broken by violence. You also talk a lot about nostalgia for Nigeria, now that you’re living abroad. In your writing, how do you navigate those feelings of pain and loss, alongside a nostalgia for this place that inflicts so much violence against LGBTQ people?

That’s the challenge that I have to deal with. I felt conflicted a lot of the time because this is a country that I love so much. It’s where I’m from. But then again, my people in the country are experiencing so much pain and hurt. What I try to do to balance it out is write. Part of my strategy is to put down all the memories that I have from Nigeria on paper. It gives me some kind of satisfaction that makes up – not quite, but somewhat – for the nostalgia. I also try to go back at least once every year, which helps, because I spend time with family and with loved ones, and I gather all that time and memory with me and take it back to the US. So between those levels of contrast, I try to create a balance.

Azuah is also the author of Sky-High Flames (2005), Edible Bones (2013), as well as collections of poetry and short stories. Her writing has appeared in numerous anthologies of African literature.

Can you talk a little bit about the experience of being a Nigerian writer abroad?

It has taken me a while to learn how to deal with the stereotypes I have found here. Sometimes I look at people and think- Don’t you know that Nigeria is just one country in Africa? Don’t you know that even though there’s so much oppression and persecution of LGBTQ people, there are actually lesbians and homosexual men who live together in peace in their communities? Everything is not one sided. There are exceptional cases that exist as well. In my own way, I try to educate people when I have the patience. Sometimes it can be quite uncomfortable to talk about how those stereotypes shouldn’t exist, considering the variety of issues and ways of living for the LGBT Nigerian.

There are people outside of Africa who would think that Africa is backwards and homophobic, but of course the truth is that homophobia was imported from Europe via colonialism. Then there are also people within Africa who say that homosexuality is un-African. As an African lesbian woman, what has the process of reclaiming those identities- African, lesbian, Nigerian, woman- been like for you?

I don’t think that being homosexual is un-African. In fact, I think being homophobic is un-African. I say that because, from what I know of my culture, there’s an acceptance and a recognition of gender roles that are not fixed, or that shouldn’t be fixed. I always talk about how in the Igbo culture, for example, women marrying women (even though it’s to perpetuate patriarchy) is the norm. It’s possible for a woman to marry a woman. In the North, they have the Dan Daudu- (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7246935.stm) men who cross-dress and play the role of women, and they’re accepted and they’re embraced in their community. Even in the Igbo culture, there are ceremonies where men can braid their hair for example, or cross-dress as women. All of that within the culture seems to indicate that this is a culture that acknowledges and embraces differences in gender expression. It also makes me sad that we inherited the British sodomy law. Britain has gotten rid of it now, but we’re still stuck with it. Christians in Nigeria are quick to quote the Bible. But it’s ironic that in Israel, Jesus’ land, they’ve accepted same sex relationships now. What I do is to try as much as I can to educate people, even though I myself still struggle with it, as a spiritual person. For those who are Christians and who are struggling with reconciling their sexuality and their spirituality or their religious tendencies, I try to talk about such concerns. When I travel around Nigeria I write about those things too, because I feel that the more we know, the more armed we become to deal with whatever issues that confront us.

I don’t think that being homosexual is un-African. In fact, I think being homophobic is un-African.

Can you talk about what draws you to writing about spirituality, whether it’s Catholicism, the Yoruba faith, or other faiths?

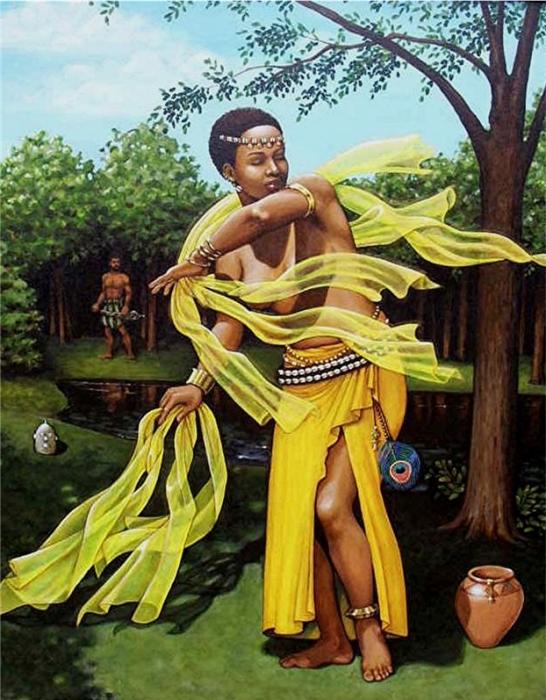

When I was growing up, I spent a lot of time with my grandmother, and she would always tell me about the river goddess of her people, and she would talk about how the river goddess is not associated with any male or any man. I would say, “Well, why is that?” And she would say, “It’s because she’s special, she’s a special woman, and she’s powerful, so that nobody may be found worthy to be her partner.” She would talk about how there are special people who don’t do what regular people do. That got me excited because even as a child of nine and ten, my friends would get excited about this boy or that boy, and I didn’t feel the same way. So I tried to think about what my grandmother told me. I would say to myself, “Oh, maybe I am that kind of special person my grandmother talks about, who is not necessarily a person who goes with the crowd, who is unique in their ways.” Then, when I got to Catholic high school, I was inundated with the image of Mary. But along the way, I combined the image of Oshun, the river goddess, and Mary the Mother of God, and for some reason I found peace in reconciling the two concepts.

Goddess Oshun. Image by Carla Nickerson.

Being at a Catholic school gave me the room to think about myself, even with the struggles and problems I’ve had trying to deal with my sexuality, mostly because I was surrounded by girls and women. I found it affirming because, unlike in elementary school when I didn’t particularly like boys, being around girls reassured me that there wasn’t really anything wrong with expressing my desires or my love for the same gender. I met a variety of girls who came with their own kinds of gifts, be it in listening, be it in being sympathetic or empathetic. It’s okay to still feel loved because at the end of the day, it’s not about what people feel or think or say, it’s actually about how you feel that is important to your growth. I also found that the Catholic Church can be loving because I was nurtured in that faith. Spending a little time in the Convent also gave me time to reflect and get closer to a higher power. It let me understand that it’s about a relationship between one and whoever the person feels is a higher power, be it a God, be it a goddess; faith is a very private thing. I was able to find the kind of peace and acceptance for myself that I eventually embraced and have tried to preach.

“Madonna and Child” by Marianne Stokes.

Where did writing play a role in exploring your identity?

It’s interesting you mention that because writing became my outlet. I was always the nerd and the girl who would be by herself in the corner. It all had to do with the same struggles. Maybe it was that I felt it more intensely than the others, but I was always very melancholic – I was always in the corner brooding. So writing became a therapy. Any time I would sit down and write about what I was feeling, even if it was about how somebody upset me or how somebody stole my snack, or about how I was interested in being friends with a particular person but I was rejected, writing it down was a way for me to make the problem vanish. That habit became a pattern, something that I held onto, and I continued expanding and writing about other issues beyond what made me start writing in the first place. So writing played a very major role in my life. I’m grateful I have that skill, and that I am able to use it to heal.

I’m also hoping to encourage LGBT writers to collaborate with screenwriters to see how we can make the textual stories visual. Maybe that way we’ll have a broader audience – I feel that when people look at stories, they tend to have a change of heart about whatever concepts they’ve held onto. And that could be a very important tool for LGBT advocacy in Nigeria.

Can you talk about what your experience has been like here in the US?

Being in the US has been very liberating because it gave me the option of exploring so many things – be it friendship, be it creative writing, be it the LGBTQ community – it gave me an unlimited landscape to explore. Then again, I realize that there are differences that made me uncomfortable at some points. For example, when I first arrived and was in Cleveland, I realized that people always had already found their niches. They had their group of friends, and trying to become a part of that group was difficult. It was difficult to break in. Again, I faced another kind of isolation. With time, I gradually created my own community, and I was absorbed into different communities. But I wouldn’t look at the cultural differences lightly because sometimes it was an issue: you could say something and you think it’s funny, but the other person doesn’t think it’s funny, maybe because of a cultural context. So I kept to myself, I tried to study the culture and the environment, and tried to understand how certain things worked. That took me a while, and I remember this vividly because when I got to the US, for about two or three years, I couldn’t write. Everything that I thought of was in my head. As soon as I discovered a literary community, which was less challenging to access, it became much easier. But I won’t forget or ignore the fact that relocation had its own effect. But at the end of the day, I’m grateful that I have what I’ll call, a new family, in America.