The Honduran Student Protests, Explained

by Sampsonia Way / July 21, 2016 / No comments

UNAH student activists cover their faces to avoid arrest. Image via Youtube user: Canal 11 – Honduras.

The student protests at the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), as described in Dina Meza’s July column, are deeply rooted in a history of academic inequity in Honduras and student-led social movements. In order to understand what is happening at the UNAH, it is necessary to understand the context of the protests, how education is accessed in Honduras, the students’ demands, and how social movements are viewed by the country’s military-backed government. Sampsonia Way compiled this primer to explain.

Who is protesting?

Students at the only public university in Honduras, the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), are protesting the privatization of higher education in Honduras. The University Student Movement (MEU) has mobilized in response to changes in academic regulations that affect their ability to attend school. The protests have spread from UNAH’s main campus in Tegucigalpa to an affiliate campus in San Pedro Sula, where 1,500 students were not able to pass the year as a result of the changes to academic standards.

What is at stake?

The protests were sparked when the UNAH passed a measure to increase student fees and raise the minimum grade to pass a class from 60 percent to 70 percent. In a broader sense, students are protesting because fees and policy decisions are infringing upon their right to a public education. They are demanding inclusion in the university’s policy making and for the university to be more transparent about how it is spending money on the education system.

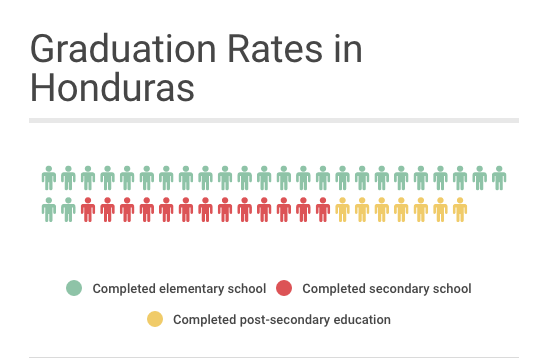

Access to education is already limited in Honduras. As of 2011, only 26 percent of Honduran youth finished primary school. Only 13 percent of those students would go on to finish secondary school, and only 7 percent of those students would complete post-secondary school.

How has the university responded?

The university officials have effectively been unresponsive to the protesters’ demands. Police have arrested students and disrupted their demonstrations.

Rutilia Calderon, the Vice Rector of Academic Affairs, has announced that the number of days lost due to protests in the second term meant that the university would cancel its third term across the fourteen disciplines, including engineering, social work, journalism, and mathematics. The MEU has argued that the cancellation is arbitrary and represents an abuse of Calderon’s power.

Why have the student protests been criminalized?

Honduras’s Constitution protects freedom of expression, assembly, and association, but authorities systematically violate these guarantees.

Protest has been stigmatized in Honduras ever since the 1963 military coup. When the military and police came back into power in 2009, Honduras saw the revival of rhetoric that spread fear, manipulated information, and supported impunity.

Today, Honduras is divided between a coalition of political, military, business, and religious powers and civil society activists who do not have a voice in the country’s politics. Business-affiliated media sources manipulate the portrayal of activists in order to serve their financial interests.

Have student protests happened in Honduras before?

Yes. Students have been at the forefront of social movements in Honduras. Educational institutions are being targeted because teachers’ unions participated in nonviolent protests against the 2009 coup. Fourteen teachers were assassinated between 2009 and 2011. In 2011, Honduras passed a law to decentralize and privatize education, and schools are now controlled by businesses and NGOs.

In 2015, high school students protested the Minister of Education’s decision to lengthen the school day. The measure threatened the safety of students who would have to travel home after dark on dangerous streets. The students were joined by UNAH students protesting hiring stipulations that excluded the majority of Hondurans from teaching careers. Four high school students were assassinated after attending a demonstration. A fifth student was found dead after she had denounced President Juan Orlando Hernandez’s inactions to a TV interviewer.

Students are not the only groups protesting. In May, indigenous groups clashed with Honduran police after the assassination of prominent environmentalist Berta Cárcares. Cárcares was a leader of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). The organization was protesting the construction of hydroelectric dams in the environmentally sensitive region of La Paz. Two other indigenous environmental activists have been murdered since: Nelson García and Lesbia Janeth Urquia.