Evaluating Asylum Seekers: An Interview with Dr. Arno Vosk

by Rachel Webber / May 9, 2013 / 2 Comments

“I find it incredible that people who have endured such suffering in their home countries should find it so difficult to get refuge in the United States.”

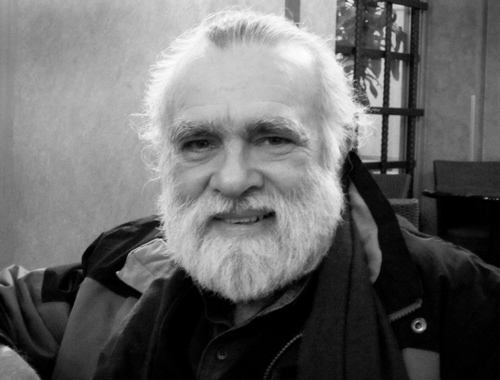

In the third installment of “Evaluating Asylum Seekers,” Sampsonia Way speaks to Dr. Arno Vosk, an advisor to a medical student clinic at the University of Pennsylvania.

The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) claimed more than 2.5 million lives and displaced huge numbers of people. Among these were at least 20,000 children, mostly boys, between 7 and 17 years of age who were separated from their families. They were named the “Lost Boys of Sudan,” by aid workers in the refugee camps where the boys resided in Africa. The term was later revived, as children fled the post-independence violence between South Sudan and Sudan during 2011–12.

One particular “lost boy,” whose name remains anonymous to ensure his protection, was five years old at the time of the Sudanese conflict. He saw his entire family murdered while their house was set on fire. He was only able to escape through an open window. Though as he climbed through the window a soldier fired at him. He never imagined that he would survive. But thanks to special coincidences—such as the open window—and the kindness of strangers, he did. He eventually migrated to the United States under the protection of a church group but after he was on his own the U.S. government tried to deport him. One of the reasons he was not deported was a medical evaluation that helped build credibility for his case when he had to tell of his hardship in court. The doctor who evaluated his case was Arno Vosk.

A volunteer for the Physicians for Human Rights Asylum Network, Dr. Vosk assists asylum seekers through medical evaluation. He remembers first getting involved with the program in 2009 when he saw a notice for an asylum examiners’ training course in Washington D.C. and decided to attend. Since then, he has been a volunteer for Physicians for Human Rights (PHR). Before seeing the notice, however, Dr. Vosk had been involved with political causes since the 1950s and practiced medicine since the 1970s—Physicians for Human Rights seemed like a great way to combine both of his passions.

In this interview Dr. Vosk discusses the role coincidence plays in keeping asylum seekers alive, his method of assessing trauma via an individual’s scars, and the difficulties people face when seeking refuge in the United States, where “fearfulness and rejection of immigrants have become an accepted part of national policy.”

Can you describe additional PHR cases that were particularly memorable or challenging?

Many years ago, listening to the story of a cousin of mine who escaped from Belgium just hours ahead of the German invasion in 1940, I was impressed by the wonderful coincidences that had happened during the journey that enabled her family to survive. Just as their car was about to run out of gas, they found the last station that had some to sell. By chance they took the right turn, when the wrong one would have led to disaster. Then it hit me: People fleeing from terrible situations who aren’t fortunate enough to encounter these special coincidences don’t survive to tell their stories.

Recently, I examined a man who was a Tutsi from Rwanda. He was 7 years old at the time of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, when the majority Hutu tribe slaughtered over half a million of the Tutsi minority. He witnessed the murder of his father by a Hutu general. Later, from a place of hiding, he listened while his mother and sister were raped multiple times. Later, trying to escape, he was caught, knocked unconscious and thrown into a pit of corpses beneath his dying brother. He survived only because some friendly soldiers happened to be passing by and heard his cries for help.

In later years he sought to testify against the man who murdered his father, who had become a powerful official in the government. As a result, two more attempts were made on his life. He bears the scars of all these attacks. He finally fled to the U.S. because the people sheltering him told him he would certainly be killed if he stayed. Fortunately, he found his way to a relative who happened to be living in Pittsburgh.

The Statue of Liberty “lifts her lamp beside the golden door.” I find it incredible that people who have endured such suffering in their home countries should find it so difficult to get refuge in the United States.

The PHR website states that volunteers determine whether or not the injuries sustained by an applicant are consistent with the account of his or her personal experiences. In what ways do you determine this?

We’ve all seen TV shows in which a forensic specialist notices a chipped toenail on a victim and determines not only the identity of the murderer, but the number of his bank account, and his favorite flavor of ice cream. In reality, it’s not so mysterious. It’s basically a logical process.

I worked in emergency rooms for three decades and saw thousands of injuries, new and old. I learned a lot about scars and residual symptoms from old trauma. PHR’s training, their manuals, put it all into a system, and the experts they have who can serve as resources have been very helpful to me.

A major part of the examination of most asylum applicants is a detailed catalog of their scars. The question is: Does the appearance of this scar fit with what the person says happened? Does it look like a bullet wound? Is it an old injury from having your head cracked by a rifle butt? A wound inflicted by a machete?

There’s very little about this, by the way, in the regular medical literature. Doctors are usually concerned with treating scars and other consequences of old injuries—not with determining what might have caused them. I had to write my own “Introduction to Scars” for the Penn medical students.

Volunteers also write affidavits for asylum seekers in court. What is this process like? What is the hardest part of this process?

The attorneys write the asylum seekers’ affidavits; these are the foundation of their case. They are written in the first person and it’s basically the asylum seeker telling their story to the judge.

The lengthiest part of my exam, at least two hours, is recording the history of that individual’s experiences in their home country that led them to flee and seek asylum here. Attorneys are interested in what I call the political details—or the whys. Why were you and your family persecuted? Why do you fear for your life if you were to return to your country? And so forth.

I am interested in the “hows” and what surrounds the gory details. What did they hit you with? Where did you have pain afterward? Did you get to see a doctor? How were you treated? How long did it take you to recover? Do you still have pain from the injury? How did you get this scar? My report is written in the third person and tells a different, and more limited, part of the asylum seeker’s story: The physical injuries they suffered.

Have you seen an abundance of asylum seekers from any specific countries?

I’ve seen more people from Africa than any other area. I suppose this is reasonable, considering the political turmoil and ongoing wars on that continent. I’ve seen several from Jamaica. We have no idea what life is like for people living beyond the confines of the resort hotels we visit! Extremely violent gangs that have close ties to the government dominate that country. I have also seen people from Latin America and Asia.

Many people in exile often experience symptoms similar to those diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, including flashbacks, a sense of alienation from others, insomnia, and depressed or suicidal thoughts. Have you noticed any patterns like this across all the asylum seekers you’ve worked with?

Many. It’s impossible for a human being to go through what most of these people have experienced and not have lasting emotional consequences. Then moving to a strange, new country, which may be safer, but not very friendly, can be very stressful. In addition to post-traumatic symptoms, it’s not unusual for people to experience depression, loneliness, or even thoughts of suicide.

What are some other symptoms that might not be as obvious and how, in your experience, do they manifest in the asylum seeker’s daily life? How does the asylum seeker live with these symptoms long term?

It’s one thing for a person to move to a new country voluntarily, say for a professional opportunity, and know they can always go back home again if they choose. It’s another thing to have to pull up roots at a moment’s notice, leave all that was familiar behind and know you will never see it again, and try to live in an strange country where people may not be very welcoming. It’s even worse if all your friends and family in your home country are dead, as is the case with many asylum seekers. This was the case with my grandparents—Jews who left Russia fleeing persecution and war. Sadness, loss, and loneliness are a common thread in their stories. How could they not be?

Adults in exile often leave behind a professional career and other long-term commitments. Have you noticed that adults have a harder time adjusting because of this?

Adults leave their careers, families, and friends. But they also have more coping skills. Children, unless they’re lucky to have family bring them, leave everything, and have fewer skills in life. So no. The adjustment is difficult for all the refugees, and when the situation in their home country is deadly only the most resourceful and lucky manage to escape.

Could you talk about U.S. policy to assist asylum seekers?

It has been an integral part of our country’s history that every nationality that has settled here hated the ones who arrived after them. German, Italian, Irish, Jewish, Chinese, Korean, African, and Mexican immigrants—all have taken their turns as recipients of this anti-immigrant hostility. Prejudice aside though, official U.S. immigration policy was pretty open until 1920. Since then immigration laws have become more and more restrictive. Not because we’ve run out of room, but because fearfulness and rejection of immigrants have become an accepted part of national policy.

How does the United States’ vision of immigration affect the lives of asylum seekers?

I wish that people already here could remember where their ancestors came from, and could realize that had immigration laws 100 years ago been what they are today, their ancestors probably would have been put right back on the boat and been deported back to wherever they came from.

Asylum seekers today are caught in our national controversy over immigration. They face a legal maze full of unfairness, that is almost impossible to negotiate unless they are lucky enough to find a lawyer who will help them for little to no fee. Ultimately, their fate hangs on decision of a single judge. Research has shown that immigration judges frequently decide cases based on their prejudices, rather than objective facts.

The asylum system should have laws that are fair, rather than paranoid and punitive as they are now, should guarantee counsel to applicants, and have cases decided by a panel of judges, rather than the single individual who decides today.

What can people inside and outside the asylum seeker circle do to help?

Families are very important. Sometimes refugees have family members living in the U.S. who are willing to help, and these folks should be sought out. Alternatively, families who are willing to form relationships with refugees to the degree that they even take them into their homes, can make a critical difference in people’s lives.

Lawyers who will work pro bono or for reduced fees are essential. Some law schools have programs in which their students assist asylum applicants. Alliances with legal resources are very important.

Finally, as in so many things, it’s not necessary to reinvent the wheel. There are organizations working with asylum seekers in many places. I’ve been working with a group of students at Penn School of Medicine who wanted to learn to do asylum exams. They found a similar group at Cornell Medical School, so they went up there to get advice and training. There are lots of resources, and people working in this field are always willing to help.

2 Comments on "Evaluating Asylum Seekers: An Interview with Dr. Arno Vosk"

The maiden name of my mother, born in Leeds England in 1900, was Vosk.

As my Vosk grandfather lost touch with his brother before WWII, my brothers, cousins and I have been trying to locate any other Vosks who might be related.

It’s an unusual name and perhaps Dr. Arno Vosk might have some information that would be helpful.

I’d appreciate your putting me in touch with Dr. Vosk.

Thank you,

Rachel Katzin Chodorov

Hi Rachel,

We will try to put you in contact with Dr. Vosk.

Thanks!

Quay Morris