Evaluating Asylum Seekers

by Sampsonia Way / May 1, 2013 / No comments

Starting on Tuesday, May 7, Sampsonia Way is launching a series of interviews with physicians that donate their time to The Asylum Network of Physicians for Human Rights. Today we present what the organization does and some of the experiences of one of PHR’s volunteers in providing evaluations for asylum seekers.

Article By Barbara Eisold, Ph.D

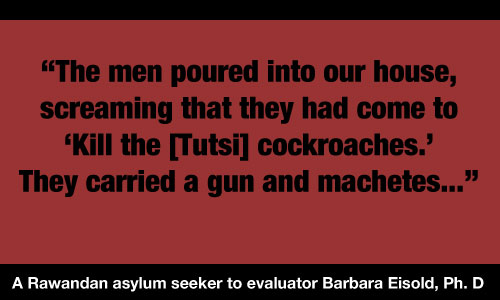

“The men poured into our house, screaming that they had come to ‘kill the [Tutsi] cockroaches.’ They carried a gun and machetes. They beat my parents and then they killed them. They shot my father and hacked my mother to pieces. They cut my sister’s arm and then pushed her to the ground. My brothers and I ran outside. They followed us and began to beat us with pieces of wood. We cried a lot. My brothers ran away. Then they knocked me down. Some of them, I don’t remember how many, took turns raping me. They stopped when a whistle blew, the sign for them to move on to more destruction. Before they left, one man said, ‘We should kill her.’ ‘She will die anyway,’ was the reply. They left me there to tend to myself. I was seven.”

I am hearing this story in my role as a pro bono examiner for Physicians for Human Rights. My client, a young woman whose life was recently threatened again, because of appearances she made before a locally organized court in Rwanda*, protesting the murder of her family, has come to America seeking asylum. My task is to get her to describe, in one long interview, what happened to her.

I have a definite agenda: after questioning her in detail, in a manner which makes it difficult for her to fake her symptoms, I shall write a report including a psychiatric diagnosis that will be submitted to a federally appointed immigration judge, in support of her application for asylum. How useful my report will be will depend not only on the clarity of my presentation, but on both the skill of the attorney who is presenting her case and the disposition of her assigned judge. In most cases**, federal immigration judges have complete discretion in deciding who will receive asylum. Some judges are very well informed, others are not.

- Physicians For Human Rights Asylum Network

- PHR Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) is an independent organization that uses medicine and science to stop mass atrocities and severe human rights violations against individuals.

- PHR’s Asylum Network is a community of hundreds of health professionals who offer pro bono forensic psychological and physical evaluations to document evidence of torture and persecution for men, women, and children fleeing danger in their home countries.

- Each year, tens of thousands of people from around the world seek safety through the complex and restrictive United States immigration process so that they can re-build their lives in the US. This vulnerable group includes survivors of torture, domestic abuse, trafficking, and other forms of persecution. They often feel they have nothing more than their own words to substantiate their suffering, but some of the most compelling evidence they can offer — physical and psychological sequelae of torture — can be documented by a health professional to make the difference between safety in the US or forcible return to countries of persecution.

- PHR’s clinicians have specialized training and expertise in recognizing and documenting the trauma of conflict, displacement, abuse, discrimination, and oppression — issues at the heart of many humanitarian relief applications. The medical-legal affidavits that they submit to courts on behalf of survivors are frequently the determining factor when judges grant asylum or other relief from deportation.

PHR’s members also use their expertise to advocate for the health and human rights of people held in immigration detention and for others negatively impacted by US immigration policies. Through their work in clinics, detention centers, courtrooms, and policy-makers’ offices, these volunteer health professionals are saving lives every day. - Click here to become a volunteer.

- Source: Physicians for Human Rights

I choose to do these evaluations for many reasons. As the United States entered World War II, I was living with my family in Washington, D.C. Because everyone’s father was involved in the war, we children learned early about prison camps. Our fear of these was intensified by newsreels, which we watched regularly when we went to see movies like Snow White. In the newsreels, Hitler spoke like a crazy man who had total control of high-stepping soldiers as they marched rigidly, in terrifying, mechanical order. On our block, there was a boy with cerebral palsy, named Ho, who walked that way. We were terrified of him.

Whenever he walked down the block, we would scream, “Hitler is coming! Hitler is coming!” and run for shelter. At times the fear was so intense that some kids cried. Later, in New York City, I had a teacher who had been in Auschwitz, a fact that everyone knew because her number was inscribed on her arm. No one discussed this. Instead, we invented a “prison” game, which we played every chance we got. The largest and most physically developed girl became “The General”; the rest of us were “prisoners.” As the General meted out punishments for unspecified infractions, once again our feelings were intense. We prisoners helped one another cope, but we knew that escape was out of the question.

The Evaluations

Perhaps it is because these childhood games made me feel surprisingly close to experiences of imprisonment and endangerment that I decided to do assessments of asylum seekers. Assessments are so goal-oriented, so rapidfire, they feel very different from the slow pace of psychotherapy. I like the contrast. However, at the beginning some aspects of the work alarmed me; I would dream about the blood-stopping nature of their tales, this happens less often now. Questioning clients in detail about their pain felt sadistic, exactly what I had been taught not to do as a psychoanalyst.

But I changed my mind about this because of client feedback. At the end of some interviews clients have thanked me saying that “although it is hard, each time helps” to get their stories in some kind of perspective. Sometimes my questions help recapture details that have been “forgotten”. The interviews also give me an opportunity to describe the value of “counseling.”

Over time I have developed a more individualized approach to questioning. Now I include questions about the courage that has sustained the asylum seeker through his/her ordeal. This can produce tales of faith and resilience that amaze me. One virtually illiterate Tibetan peasant was held in solitary confinement for nearly a year and beaten regularly. The Chinese wanted information about some nuns for whom he cared deeply. “How did you survive without losing your mind or telling them?” I asked. “I decided that fear was my worst enemy,” he said. “So I convinced myself that the beatings were normal, nothing to be terrified of.” With this conviction and his faith in the Dalai Lama he remained in charge of himself and revealed nothing about the nuns.

One woman, beaten and serially raped over the course of days by opposing soldiers in her African country, then imprisoned with other women, many of whom died, survived because she pretended to be an innocent country girl, uneducated, and therefore not a member of the opposition. What sustained her, I asked, throughout these days? She told me that she could not bear the thought that no one would care for her mother if she were killed. In listening to these stories, I am struck by how deep attachments, combined with unruffled decision making motivate people to survive.

The Psychoanalyst’s Lens

My curiosity about my clients as individuals, why they are fleeing, and how they survive, is deepened by my psychoanalytic interest and training. I seek to understand everything I can about the person’s motivation, strength of character, intelligence, and survival skills. In my report I summarize my understanding and focus as much as possible on feelings.

Judges, attorneys, and agency staff have commented how helpful my evaluations are. Rather than providing a diagnosis and list of symptoms, I believe my psychodynamically oriented questioning yields a much fuller picture of the client, hopefully enabling the court to make an informed decision. But not always.

When the case finally goes to court, I am asked to stand by the telephone in case the judge wants to question me. Twice I have been asked to make an in-court appearance. The small, courtrooms I saw were modern and clean, in contrast to the sub-standard conditions in which illegal immigrants (including asylum seekers) are often housed (Dow, 2004).

The cast of courtroom characters includes the judge, the client, his/her attorney, a translator, and an attorney for the government. The latter is there to question the asylum seeker’s statements, which can be done with virulence. On the days I attended, one case was won, to great rejoicing, the other, lost. An appeal, however, was certain.

____________________

*Local courts, called Gacaca Courts, were organized to speed up trials of genocide perpetrators. More information.

** There are some few situations in which, by law, judges must grant political asylum. Among them are threat of Female Genital Mutilation or on-going spousal abuse.

Additional References:

Dow, M. (2004). American Gulag. Berkeley, CA.: Univ. of Ca. Press.

Material originally published in Physicians For Human Rights Asylum Network

For those of you who would like to volunteer to evaluate people seeking asylum, here is a list of organizations to contact.