The Michael Moore of India

by Vijay Nair / January 11, 2013 / No comments

In the wake of tragedy, let’s listen to our artists.

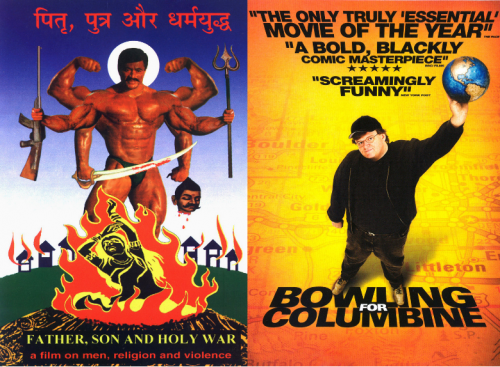

Posters for Anand Patwardhan's Father, Son, and Holy War (1995) and Michael Moore's Bowling For Columbine (2002)

Towards the end of 2012, tragedies dominated the headlines in both the United States and India. A few days after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary school in Newton, Connecticut, New Delhi woke to the news of the gang rape of a 23 year-old girl in a moving bus. Apart from the sexual assault, the victim and her companion were also brutalized by an iron rod. A fortnight later she succumbed to her injuries in a hospital in Singapore, where the government had flown her for better medical care. Possibly the most distressing aspect of the incident was that it was a minor, not yet 18 years of age, who lured the girl and her companion inside the bus by promising to drop them off where they wanted to go. He was among the six men in the bus who committed the heinous crime.

These tragedies have led to a number of protests in both countries against governmental policies that have played a role in encouraging violent crimes like these. Nevertheless, one can’t help wondering in this context whether these tragic incidents could have been averted if the work of two leading documentary filmmakers from these nations— Michael Moore of the United States and Anand Patwardhan of India—had been given their rightful due. It may be timely and worthwhile to revisit these directors’ films, such as Moore’s Bowling for Columbine and Patwardhan’s Father, Son and Holy War, in the aftermath, with the hope that they could be an excellent starting point for affirmative action to happen. After all, isn’t the ultimate goal of all relevant artistic and cinematic expressions to make the world we inhabit a better place to live?

There is a connection between the two filmmakers as Anand Patwardhan has sometimes been referred to as the Michael Moore of India. Although, Patwardhan is not only four years older than his American counterpart, he also started his cinematic activism more than a decade before Moore directed his first film. Possibly the difference in the economic clout of the two nations, as well as the relative maturity of their respective democracies, have played a role in catapulting Moore into a global phenomenon while Patwardhan still has not been able to muster the popularity he deserves, even within his own country.

Moore’s achievements include an academy award for best documentary feature in 2002 for his seminal work Bowling for Columbine, which explored the causes for the Columbine High School massacre in 1999. There are too many parallels between that tragedy and the one that took place at Sandy Hook Elementary to be ignored, and it is sad that the lessons from Moore’s film have not been taken seriously by the world’s most powerful democracy. Moore himself seems to have turned into an increasingly marginalized figure as of late, isolated on party lines and by his entire persona. Both his weight and millionaire lifestyle have turned him into a soft target for critics, some of whom have called him anti-American.

Back in the world’s most populous democracy Patwardhan hasn’t fared much better with his opponents. Trenchant critics belonging to Indian right-wing fundamentalist parties are only too happy to denounce him as a traitor and a seditionist. The filmmaker has had to repeatedly evoke memories of the role his family played in India’s struggle for freedom to prove his patriotic credentials. But considering the fact that many of the films he has directed have been unrelentingly critical of the Hindu orthodoxy, that piece of history has not shielded him from his critics. What has also led to the furious backlash against him is that Patwardhan has made comments to the effect that fundamentalism is far more deeply entrenched in India than in neighboring Pakistan. His logic being that the people of Pakistan have never elected a fundamentalist party to power, while Indians have.

In an illustrious and prolific career spanning over four decades and 14 documentaries, Patwardhan’s films have time and again been banned by the Indian Censor Board. Undaunted, the man has waged long and lonely battles in court to ensure that not only are the films he makes screened in his country, but they are also shown on the government-owned television channel, Doordarshan. The irony is that the government bestows many national awards upon Patwardhan for the films he makes, but at the same time his films are considered unfit to be screened. On more than one occasion Patwardhan has commented wryly that he has been forced to play the dual roles of being a filmmaker and a lawyer thanks to all his legal battles with the Indian Censor Board.

The subject matter of his documentaries ranges from the slum dwellers of Bombay, to the demolition of the Babri Masjid, to India’s nuclear ambitions. They are all sharp, incisive works that make viewers question the outdated social mores of traditional society that have lead to the oppression and subjugation of minorities.

My personal favorite among Patwardhan’s films is evocatively titled Father, Son and Holy War, which finds a mention in DOX 50, a book that contains 51 essays on 51 films that have left an indelible impression on the authors’ lives. Father, Son and Holy War is a searing indictment of the feudal and patriarchal mindset of Indians. The work unfolds in two parts. The first part is called “Trial by Fire,” a reference to what Sita, the wife of the Hindu god Rama, had to undergo to prove her fidelity to her husband after she was kidnapped by the demon king Ravana. Patwardhan links this part of mythology to the communal fires that rabid political leaders in India repeatedly douse citizens with.

There are also references to the archaic practice of sati, in which, during medieval times, the living wife jumped onto her husband’s funeral pyre to prove her chastity to the world. Patwardhan’s argument is that cultural baggage like this does nothing for the rights of minorities, especially women. The second part of the film is entitled “Hero Pharmacy” and explores the notion of ‘manhood’ in the context of strife.

Indian society is currently in a state of flux. Urban spaces are comprised almost equally of modern, empowered youth who are educated and demand their space under the sun and migrants with traditional mindsets that, in a patriarchal framework, can only grant women the status of objects to be consumed. Acts of violence against women stem from these types of regressive mindsets and unless the politicians in India stop playing the game of running with the hare and hunting with the hounds, women will continue to be at the receiving end of violence.

I believe Father, Son and Holy War should be compulsory viewing for high school students in India in order to gender sensitize them.