The Satire of Obscenity

by Vijay Nair / November 14, 2012 / No comments

Revisiting the history of two Indian writers, on trial for their work.

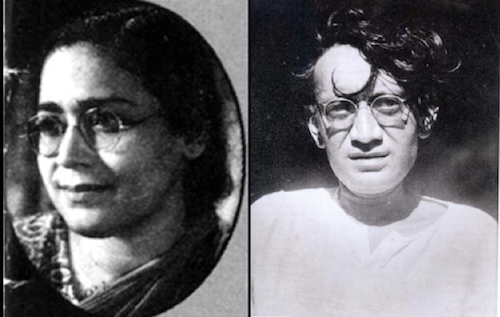

Left: Ismat Chughtai. Photo: YouTube user radiopakistanonline. Right: Saadat Hasan Manto. Photo: Shahzad.gohar. Creative Commons Licensed.

Motley, the Mumbai theatre group run by the actors Naseeruddin Shah and Ratna Pathak Shah, has in its admirable repertoire, a play called Manto Ismat Hazir Hain. The play pays tribute to two of the best writers of short fiction in Urdu, Saadat Hasan Manto and Ismat Chughtai, and their indomitable spirit, which refused to kowtow to the dictates of conventional morality. Both of these writers were charged with obscenity in British India and lived to narrate the stories of their trials, not without a dash of humor. Manto Ismat Hazir Hain is a dramatization of the trials they had to face. Loosely translated, the title of the play means Manto and Ismat are present, an announcement that informs the court that the accused are ready to be tried.

Manto and Chughtai were contemporaries, born within three years of each other in the pre-partition India of the twentieth century. Later, their writing brought them together as friends and literary foes. Manto was to famously remark that if he had been born a woman, he would have been Ismat Chughtai, and if Ismat Chughtai were born a man, she would have been Saadat Hasan Manto.

Chughtai had to face the music only once for the first short story she published, called “Lihaf” (Quilt), but Manto was tried six times on the same charge for different stories he wrote. Neither of them went to jail, although Manto did have to pay a fine once. Legend has it that their witty repartees during their respective trials managed to tickle the most conservative of judges, allowing them to get off lightly.

Even the most trenchant critic of Islam and its followers is likely to fall in love with the inherent lyricism of the Urdu language. There is a certain kind of music and rhythm in the way the language is spoken and written. In recent times V. S. Naipaul has come under a fair degree of criticism on the Indian sub-continent for giving a one-dimensional interpretation of the violence and brutality during the Muslim invasion of India in medieval times, while totally ignoring Muslim contributions to Indian culture through art, architecture, music, and poetry. But it has to be said that neither Manto’s nor Chughtai’s prose lend themselves to romanticism. Their stories are biting satires on the reality of the times they lived in.

The story that got Chughtai into trouble dealt with the pathos of a beautiful woman who is married to a much older man. Her husband has a harem full of young boys and has totally forgotten his wife, who is confined to the zenana, the women’s quarters. Lonely and neglected, she starts an affair with her middle-aged maid. The narrator of the story is a young girl who visits her aunt, the protagonist, and is forced to share a room with her. She is unable to understand why, in the dark of night, the quilt that provides cover for the two clandestine lovers assumes such grotesque shapes before her unbelieving eyes.

The story sparked outrage when it was first published in 1941. Readers assumed the writer was a man. When they discovered that a woman had written the story, all hell broke loose. Chughtai belonged to a conservative Muslim family and to even earn the two college degrees she had involved long negotiations with the patriarchal system. Women writers were scarce those days and a woman who wrote about homosexuals and lesbians was never heard of, let alone condoned. The trial lasted for four years. At the end Chughtai was acquitted on grounds that there were no explicit homoerotic passages in the story. Delicately nuanced and narrated through the eyes of a prepubescent girl, the story has a wickedly funny undertone. The quilt itself seems to be a metaphor for the cover required to conceal the sexuality of men and women in an orthodox society.

On the other hand, there was nothing coy about Manto’s “Thanda Gosht,” one of the stories that led to his run-in with the law. The story opens as the protagonist comes home after looting and killing members of a particular community during the partition riots. His wife tries very hard to seduce him and gets increasingly frustrated. He is finally forced to confess he has turned impotent ever since he tried to rape the corpse of a girl he abducted from a family he had slain. The story contains explicit passages written in a bitingly satirical style that makes readers chuckle before they get to the horrific climax. Many of Manto’s stories employed black humor to condemn the partition of India.

His most accomplished work “Toba Tek Singh” unfolds three years after the partition. The governments of India and Pakistan decide to exchange the inmates of their lunatic asylum. The Hindu and Sikh inmates of the lunatic asylum in Pakistan are to be sent to India, and the Muslim inmates of the lunatic asylum in India to Pakistan. When the protagonist Bishan Singh finds out that the village he hails from is now in Pakistan, but he is being deported to India, he refuses to comply and lies down in the no man’s land between the two newly created countries.

The partition of India also ensured that the two writers now belonged to two different countries. Manto went to Pakistan while Chughtai stayed in India and joined the progressive writer’s movement. Manto’s life spiraled into depression and alcoholism and he died young, at the age of 46 from liver cirrhosis caused by consumption of cheap liquor, leaving behind his wife and three daughters. More than half a century after he died in dire poverty, the government of Pakistan conferred the country’s highest civilian award on him in August, 2012.

Chughtai, on the other hand, continued to live in India with her filmmaker husband. Although never tried for obscenity again, some of her books were banned because of their feminist content. In 1973, Garm Hawa, a feature film based on one of her stories was released. It won universal acclaim in the country and abroad, and was nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival. Despite her creative triumphs, the biggest literary prizes in India—like the Sahitya Academy Award and the Jnanpith award, which she richly deserved—eluded her. Chugati died in 1991 at the age of 76, having lived life on her own terms.

The peculiar thing about the Manto and Chughtai parable is that more than six to seven decades after their controversial stories were written, it is likely they would garner as much protest and as many charges of obscenity in both countries. The only difference may be that while in those days of relative civility, unscathed by Islamic extremists and Hindu fundamentalists, the writers managed to receive fair trials and continued to write. Now it is quite possible that they would be plagued by death threats, if not having actual bullets fired at them.

That is the biting satire of the times we live in.