Best European Fiction: A Conversation on Translation

by Joshua Barnes / April 12, 2011 / No comments

John O’Brien talks with Gonçalo M. Tavares, Igor Štiks, and Peter Terrin about literature in translation at the 2011 Passa Porta festival in Brussels.

The American Dalkey Archive Press has a nose for finding talent in contemporary writing outside the United States. One condensed example of this is its compilation of translated European work, Best European Fiction.

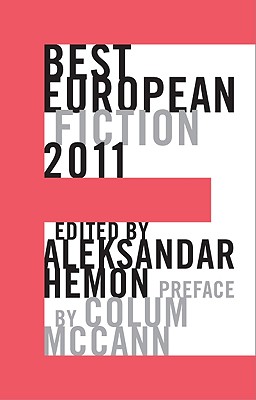

Best European Fiction 2010 was the inauguration of what is now an annual anthology. Edited by acclaimed Bosnian novelist Aleksandar Hemon, this series is a window into contemporary literary scenes throughout Europe, where the next Kafka, Flaubert, or Mann is waiting to be discovered.

At the Passa Porta Literary Festival in Brussels, Dalkey Archive Press’ publisher John O’Brien talked to three authors featured in Best European Fiction: Igor Štiks from Croatia, Gonçalo M. Tavares from Portugal, and Peter Terrin from Belgium.

In this Sampsonia Way exclusive, read part of their hour-long conversation, which took place on March 27 as one of the Passa Porta Festival’s 100 talks, readings, and literary encounters.

John O’Brien: Do you think it’s fair, or is there a point to gathering writers according to continent, and putting them all in one body?

Igor Štiks: It’s a difficult question. We are all part of a world literature, but unfortunately we cannot write in a world language—it doesn’t exist.

We should start by changing this perception that there is a West, there is an East, and there is something in the South East. Especially for me, coming from the Balkans, people just 200 kilometers away are saying: “Oh well, you know, it’s so complicated down there. These people are different.” We need to get out of this provincial box and simply understand that there is no border there in Bosporus that separates us from other people. Obviously, everything that is happening is not only happening to the people there.

In this respect the anthology is a good choice: you decided that you’re looking for a common denominator, and you find a gentle approach. However, what we see in the anthology is both a lot of commonality and a lot of diversity.

Gonçalo M. Tavares: The only strong identity is the language. The most interesting point about these kinds of books is that writers from various languages come together under the same language. There is a philosopher who states that the human being is an organism driven by desire and European identity is not an issue of a singular desire. There is no communal European identity. There are many.

Peter Terrin: What struck me is that you [Gonçalo] said that the strong identity is the language, but there are hundreds of millions of people speaking Portuguese. With my language it’s slightly different. I have a very small language, and in fact, in Flanders there is a slightly different language from Dutch in general.

My identity is not really in my language. For me, it is in books like Best European Fiction. And if you read the stories in the anthology—as you said—there is something European in there.

Best European Fiction: 2011. Published November 2010, by Dalkey Archive Press.

John O’Brien: Do you care how the work fits within a new culture? Are you more concerned with translation’s accuracy to the original or do you just let it go?

Igor Štiks: When it comes to translation there is an unwritten contract between the writer, the translator, and the editor. Ultimately, the writer simply has to trust these people. There is a moment when you have to, as you say, “Just let it go.”

The translated text is unlike the original because it’s a collective work and it has to be understood as such. Therefore, any insistence on absolute control from the writer or editor is bad for translation.

Even though some mistakes can happen, the biggest fear of every writer is that the most important things will be missed or altered, and that the work will get an entirely different resonance somewhere. The best thing is when you have someone who will really puts the work into another language as if it was written in that language.

Of course, the fourth party in this contract is the readers. My experience of having ten or eleven translations is that it’s curious to see what readers discover, why they buy the book, and how certain topics will resonate differently. This gives you an idea about the richness of your own text. That’s why for every author, if he or she can get translated, it’s always a feast.

Gonçalo M. Tavares: We have to trust the translator when we can’t understand not just a word, but a letter of the language. Sometimes I can’t even understand my own name written out. The most important thing for the translator to catch is the ambiguity of the original text; it’s important not to put the sentence to the right or to the left if the sentence is in the middle.

Peter Terrin: While writing, Haruki Murakami is already thinking about the translation. He tries to keep the sentences as simple as possible so that the translation won’t have big problems. I wouldn’t go that far, I think, but, I’m not Murakami so…

Anyway, I think it’s very interesting to see how a translator reads your work. It’s amazing how each language is so detailed and different. You can just hope that the translators are as excited as you are, and that that’s reflected in the translation. There really isn’t anything you can do.

Best European Fiction: 2010 Published January 2010 by Dalkey Archive Press

John O’Brien: Once, I was editing a text and the original said something like “as dry as the Mississippi Valley in the summer.” Anybody who knows the Mississippi Valley knows it’s quite humid and wet. I was facing a problem: Is this a joke? Is it supposed to be an ironic statement? Or, was the original editor sloppy? Was the author sloppy? Knowing the author wouldn’t respond to my queries for months, I decided to change it. The translator was aghast. When I met the author a few months later and told him about the change, he responded, “Oh thank God! I’m really lazy when it comes to those things and my editor had no idea what the United States is like.”

So in that case it was fine. But this is a struggle that happens all the time and sometimes the writers end up being the victim of this process. Would you prefer to be working closely with the translator, even if you don’t know the language, in order to avoid this kind of situation?

Igor Štiks: I would rather a translator to point out errors or inconsistencies instead of deciding what it should be. I think this is another problem relating to the industry: here is the author, there is someone who bought the rights. Very often these buyers, or the editor, don’t want to meet the author and they are going to commission a translator who won’t be part of the process either. The translator will just deliver the text, then the editors will work on this text, and nobody speaks to one another.

This happened to me. My book came out with another title, which is fine—if somebody asks before they change it. Of course, the translator didn’t know about the cover, and we didn’t agree about many other things. I never got a copy. The bad story of collective work.

Gonçalo M. Tavares: I prefer the translator who asks some questions, but not a lot of questions. About the final translation, I think the important thing is to maintain the health of the text. It’s like a short Thomas Mann story in which two friends who get in an accident together exchange heads. So you’ve got John’s body with Paul’s head, and Paul’s body with John’s head. Then John’s wife comes in and who does she look at? She looks at the head of her husband. So this is the point: the head of the text is most important to…

Peter Terrin: It also depends on the woman, of course…

Igor Štiks: …and the body of Paul…

Peter Terrin: I don’t have enough experience to really answer the questions, but I do recognize the mistake that John O’Brien talked about. If the writer is alive, the translator and the editor should contact him. But if you translate books and the writer is not alive, What do you do then? I think that is another story.

John O’Brien: I’ll just add an anecdote from seven or eight years ago. There was a French book we were translating and there was a sentence that came from the translator: “He began to climb the curtains.” The problem was that there were no curtains mentioned before or after this. There was no context to tell you if this was a metaphor or not. Or, as the character was a little bit goofy to begin with, perhaps he literally started climbing the curtains. So we sent it back to the translator, and the translator said, “That’s it. That’s the only translation that can be made of this.”

It just so happened a French graduate student arrived on campus [at the University of Illinois, where Dalkey Archive is located]. So the first day she arrived, I showed her the passage and asked, “Is this guy climbing the curtains?” And she said, “Of course he’s not climbing the curtains! Why would you think that?” I answered, “Because I just read the English version. Tell me what it means and stop fooling around with me.”. And she answered, “It means he’s sexually frustrated.”

These are some of the complexities that go into translating work. Both of these volumes of Best European Fiction are examples: every one of these stories had to be both carefully translated, then–we hope–carefully edited without totally violating the text, as can sometimes happen as well.

Read more exclusive content from Sampsonia Way’s trip to the 2011 Passa Porta Literary Festival in Brussels.